Editor’s Note: Welcome to our weekly Reality Check column where C-level executives and advisory firms from across the mobile industry share unique insights and experiences.

This week’s column continues the regulatory discussion started in late November focusing on the touchy issue of paid prioritization. To begin the debate, let’s get grounded on a few key assumptions about today’s broadband user:

1. Broadband is rarely as fast as consumers want. Unless you live in Kansas City (Google Fiber), or happen to have a high budget for bandwidth, this is the case. As my former Sprint colleague John Garcia said: “I can never be thin enough, have enough hair or have enough bandwidth.”

Believe it or not, there are many in this readership who disagree (some strongly) with this premise. These are not the “Bell heads” of the 1990s, but well-meaning engineers who maintain that slow speeds originate with poorly engineered host servers (e.g., Netflix servers in California) and that condition continues throughout the network. To some extent this could exist as a temporary condition – turn up a neighborhood on AT&T GigaPower and some of the servers will be overwhelmed. Within days (perhaps hours), this condition is fixed. Regardless, the premise holds that bandwidth demand continues to outstrip supply.

2. Most consumers live in constrained economic conditions that drive discrete economic choices. Affordable bandwidth before any subsidy is critical to the advancement of Internet content. The Department of Labor recently announced that the average hourly wages of production and nonsupervisory employees rose 2.2% to $20.74. For comparison, Comcast’s high-speed Internet average revenue per user is about $45 and rising 3% annually. While consumers may make choices to increase high-speed Internet expenses in the short run, there comes a time in any economic cycle where another consumer expenditure (e.g., home phone) is substituted.

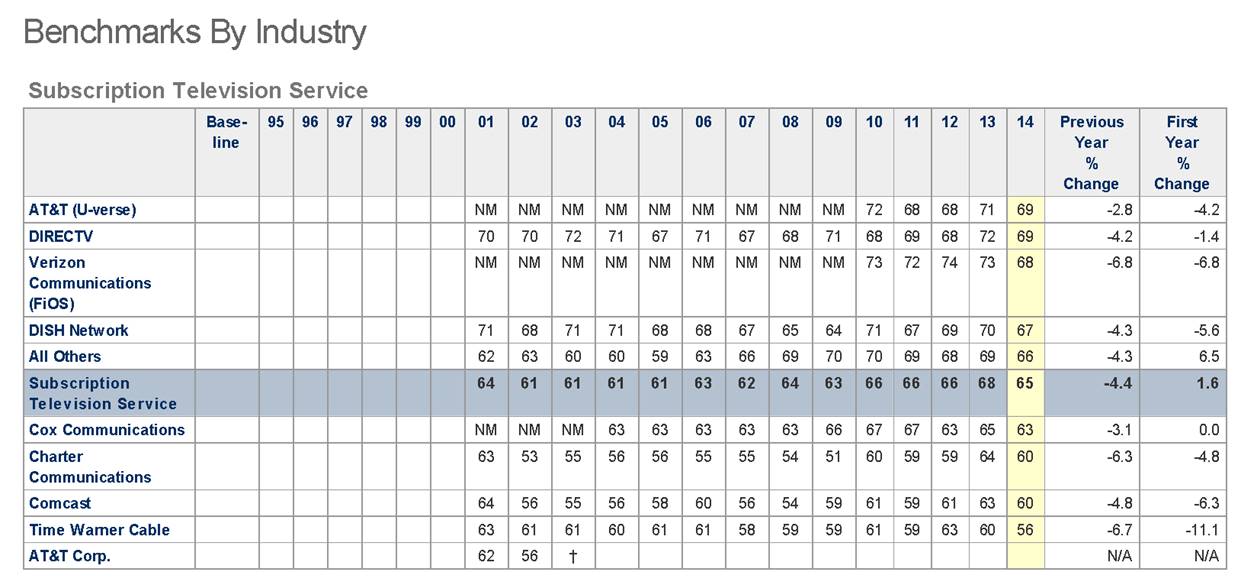

3. When broadband goes down, the home goes down. Because of Wi-Fi connectivity, more devices use the home router than ever. In fact, most cellphone providers have integrated home data connectivity into the phones’ policy manager making this process completely seamless. With the exception of smartphones, most devices do not offer alternate network options (e.g., Verizon Wireless or AT&T Mobility networks). Broadband dependency has driven up consistency and responsiveness expectations and, to a large extent, broadband service providers have done a poor job of keeping up. Here’s the latest ACSI trending data for broadband service providers:

The measurements above are for subscription television services due to the fact that ACSI’s measurement for high-speed Internet services is brand new (two data points). It is not surprising to see that overall satisfaction is on a downward trend. As mentioned earlier, consumer expectations continue to rise as more devices consume more content through Wi-Fi.

Home connectivity type and quality can make a big change in customer satisfaction perceptions. While only two data points, it is no surprise that the top two rated high-speed Internet providers in the ACSI survey (see link above) are Verizon FiOS (71 score) and AT&T U-verse (65 score). What is surprising is that the “all others” category (which includes companies such as Wide Open West, Bright House Networks, Cablevision, Mediacom, SuddenLink, etc.) have consistently scored higher than their larger peers. Satisfaction is not dependent on scale. In fact, the opposite may be true.

Bottom line: Bandwidth demand is growing faster than consumer incomes. More devices are connecting to Wi-Fi networks in homes and businesses. Service consistency and responsiveness are not meeting expectations and, as a result, consumers hold a very dim view of their current providers.

Using incentives to drive communication service provider behavior

Many of us saw firsthand federal and state government use of legislated incentives to drive carrier behavior. To enter into the long-distance business in the late 1990s, Bell Atlantic/Nynex, SBC, Bell South and US West had to satisfy 14-point competitive checklists on a state-by-state basis. They were hotly disputed, but provided a basis for substantial revenue opportunities for both the incumbent carriers and competitors.

Newly legislated incentives provide a clear and unambiguous alternative to recently proposed solutions. Applying today’s broadband service provider rules to laws that were developed before widespread adoption of Wi-Fi, smartphones and streaming content is ludicrous. Veto-proof rules should be crafted with the help of the new Congress (led by 54 Republican senators and 246 Republican representatives) to achieve all of the objectives above. Incentives are needed.

A simple legislative proposal to end the paid prioritization debate

Here is a simple proposal to end the debate over paid prioritization:

1. All carriers with more than 100,000 total high-speed Internet subscribers will be subject to daily high-speed Internet certification tests conducted by independent third parties.

2. These tests will measure peak bandwidth speeds attained from the customer premises to all interconnection points in a given metropolitan statistical area (most communication service providers measure this today in their network monitoring platforms). Peak bandwidth times vary, but generally occur between 6 p.m. and 11 p.m. local time. Sampling methodologies will be approved and administered by the Federal Communications Commission.

3. These speed tests will only be concerned with peak bandwidth throughput and not content type.

4. If 95% of the measurements over a 180-day period exceed a certain speed (my guess is the FCC will want to see 50 megabits per second in most MSAs and 25 Mbps in secondary and tertiary markets), the communications service provider can initiate paid prioritization discussions and enter into paid prioritization agreements.

5. The busy hour qualification for future years will be increased using market-based – as opposed to arbitrary government – measurements. New technologies will assuredly drive more bandwidth needs, and communication service providers will need to plan for this inevitability.

6. If the communications service provider fails to meet the new test, a (six-month) cure period will be established. During this cure period, they cannot sign or implement any new paid prioritization agreements. If they do not meet the terms during this period, they will incur a fine equal to a certain percentage of all current paid prioritization revenues – 50% would be a good starting point as paid prioritization services will have high incremental margins.

7. All terms of paid prioritization agreements will be publicly disclosed.

This is the start of a straightforward proposal. Admittedly, it does not address the use of paid prioritization in rural markets or with very small communications service providers, and it relies on a 180-day measurement period to certify throughput (this could be an issue in harsher climates like Buffalo where many consumers enjoy the outdoors during the summer, but are more confined during the winter).

Admittedly, the bar is set high enough to exclude wireless carriers from participating today. It provides an incentive, however, for further technology developments and increased spectrum investment. Most importantly, it keeps the Title II hands off of the fastest-growing part of the communications world.

Despite some shortcomings, this proposal provides a regionally measurable incentive to further monetization of broadband networks. It provides “public” lanes that will quickly and safely deliver Internet content (there is an immediate benefit should YouTube and Netflix move some of their content to faster lanes). It has a series of checks and balances to keep costs in check and penalties to prevent lax or bad behavior. Unlike elements of the 1996 Telecom Act, this proposal plans for change and creates an indexed, third-party measure to continue speed improvements.

On top of this, every element of paid prioritization agreements will be out in the open. While some may resist such open disclosure (although this is common practice with switched access and interconnection agreements), it will provide a clear equation to would-be challengers.

Best of all, consumers win big with this proposal. Carriers need to meet bandwidth throughput metrics for an extended period of time prior to receiving the rewards of paid prioritization, replacing harmful legislation that would make bad problems worse. Price caps, a guaranteed competition killer, are removed. With competitive incentives intact, the possibility of digital-subscriber line alternatives such as those described by Ars Technica now exist.

The new Congress, along with the FCC, holds the keys to the future of the Internet. Focused fixes under the overall umbrella of “no blocking” and “shared interconnection” can be implemented quickly. The futures of communication, entertainment and education hang in the balance. In the words of the most interesting man in the world, “Choose wisely, my friend.”

Jim Patterson is CEO of Patterson Advisory Group, a tactical consulting and advisory services firm dedicated to the telecommunications industry. Previously, he was EVP – business development for Infotel Broadband Services Ltd., the 4G service provider for Reliance Industries Ltd. Patterson also co-founded Mobile Symmetry, an identity-focused applications platform for wireless broadband carriers that was acquired by Infotel in 2011. Prior to Mobile Symmetry, Patterson was president – wholesale services for Sprint and has a career that spans over 20 years in telecom and technology. Patterson welcomes your comments at jim@pattersonadvice.com and you can follow him on Twitter @pattersonadvice.

Photo copyright: algre / 123RF Stock Photo