This has been a week filled with news – Mobile World Congress, analyst conferences and the normal course of business – and regulatory conjecture. I have decided to stop trying to figure out what fine-tuning the Federal Communications Commission is doing between the vote last month and the final release of the Report and Order. They issued a blog post last Tuesday trying to explain the lag and it only raised more questions with analysts and media alike.

One novel idea I think the FCC should consider is to follow the lead of “Unfinished Business,” a movie currently in theaters, and offer free photo stock for all communications services providers to insert into their PowerPoint presentations. Imagine a presentation on sponsored data with Commissioner Mignon Clyburn showing a quizzical (or downright skeptical) look; a thumbs-up from Chairman Tom Wheeler; or the disapproving furrowed brow of Commissioner Michael O’Rielly. It would bring some fun back into boardrooms everywhere.

When is a cable provider not a cable provider? Cox’s answer below:

Before moving on to Comcast news, there is one new regulatory item worth mentioning – those of you who peruse my LinkedIn feed already saw my thoughts on the topic Friday. Cox Communications, the perennial winner of the “good guys of cable” award, not to mention that they have been the breeding ground for both Comcast’s and Time Warner Cable’s commercial services business unit presidents, took to the media-sphere excoriating the FCC for their nuanced definition of a “cable company.”

At issue is a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking issued by the FCC in late December designed to make it easier for over-the-top providers to broaden their content lineups by classifying themselves as multichannel video programming distributors. Currently, unless the provider actually controls the transmission layer, content companies and cable (sports, news) programming divisions do not have to engage in retransmission discussions.

Not surprisingly, Cox takes the position that the FCC should continue with its current definition of “channel,” which was reaffirmed in 2010 and 2012 (MVPD rights would only extend if the OTT provider also controlled the transmission path). This would eliminate many competitors who seem to be thriving without offering local broadcast content.

But Cox goes further, imploring the FCC to confirm and enforce the classification of AT&T U-verse and Google Fiber as cable companies. Cox succinctly lays out their argument to the FCC as follows:

“Just as the interests in avoiding competitive distortions warrant establishing a level playing field for all MVPDs if OTT providers are deemed MVPDs, they likewise justify Commission action to ensure that all entities that meet the definition of ‘cable operator’ under the Communications Act – including self-styled ‘IPTV’ providers such as AT&T and Google Fiber – comply with the duties attendant to that classification. The NPRM appropriately proposes to clarify that cable operators’ provision of managed IP-based services over their cable systems does not alter the classification of such offerings as ‘cable services’ under the Act, and that, by contrast, OTT services are not cable services regardless of whether they are provided by a new entrant or traditional cable operator. But the NPRM fails to call out that its analysis of IP based video services undercuts the strained efforts of AT&T and Google Fiber to maintain that their IP cable services are somehow exempt from cable regulation. Such claims have no legal or factual basis, as the NPRM implicitly recognizes. The Commission should make that understanding explicit and should not permit video distributors to flout their duties under Title VI.”

Frankly, I had no idea that Google and U-verse sought to designate themselves as something other than cable companies. They market themselves as an alternative to cable company video programming (unlike SlingTV). They compare their channel line-ups to the incumbent cable company in their promotional material. And they package and price their services using tiered and premium structures straight out of the cable playbook. So if AT&T and Google swim, walk and quack like a cable duck, aren’t they cable providers? Kudos to my friends at Cox for publicly discussing this issue and exposing the unique regulatory interpretations of their competitors.

California may have killed the Comcast/Time Warner Cable merger

While many of you have been following the federal – FCC, Department of Justice – approval of the Comcast/Time Warner Cable merger, some long-time cable observers warned me that “as goes California, so goes the country” with regard to conditions and approval.

On Feb. 13, California delivered Comcast and Time Warner Cable a personalized valentine, which included the approval of their proposed merger, provided that the following conditions are met:

· The merged entity’s classification and regulation as a common carrier;

· Mandatory provision of (voice) LifeLine services;

· Offer 25 megabit per second down/3 Mbps up speeds throughout the merged entity footprint within five years;

· Offer standalone broadband service at prices no greater than Time Warner Cable’s current standalone prices for the next five years;

· Meeting (or exceeding) California’s diversity requirements (called GO 156);

· Specific website design practices;

· Battery backup requirements for all voice customers;

· Adopting Time Warner Cable’s practice with respect to third-party equipment (e.g., Roku) interoperability;

· Non-interference with voice services;

· Building out (presumably at Comcast’s cost) to additional schools and libraries;

· Agreement to not oppose any municipal broadband (wireline or wireless) network plan for five years after the merger closes;

· Increased reporting requirements for customer privacy complaints;

· Significant expansion of Comcast’s existing Internet Essentials program – doubled speeds, simpler sign-up processes, and a “flexible” 45% penetration goal within two years;

· Improved customer service requirements; and

· Flocks of partridges and groves of pear trees (my insertion, although some of you would not be surprised to see the California Commission insert this environmentally friendly requirement).

Not surprisingly, Time Warner Cable and Comcast jointly filed objections to the requirements on Friday. While some of the items above could be resolved, is it likely that Comcast and the California Commission could reach a middle ground on utility regulations, massive Internet Essentials program expansion and tacit support for municipal broadband deployments?

The California Commission and Comcast appear to have reached a stalemate. At best, it’s two months of hard slog to define which new regulations Comcast will have to obey as well as the penalty severity should they decide to ignore some or all of them. At worst, California did the dirty work for the FCC. Look for more color on the process in the coming 45-60 days. No news is likely bad news on this front.

Comcast is the envy of the wireline industry

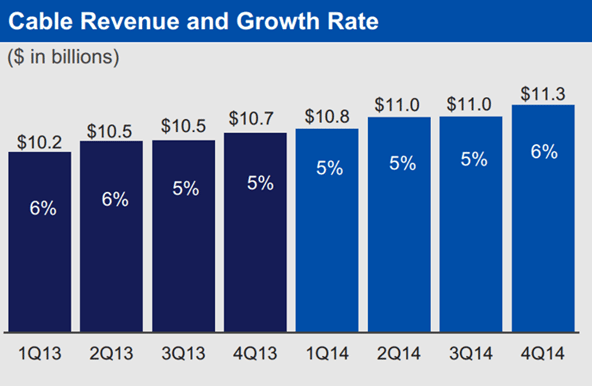

For all of the ad hominem attacks on Comcast as a large behemoth with horns, its earnings for the fourth quarter and full-year 2014 were spectacular. No other wireline company comes close to its growth on an absolute or relative basis (AT&T and Verizon Communications’ wireline businesses shrank in 2014; Comcast’s cable division grew $2.3 billion).

For all of the attacks Comcast has taken in the net neutrality debate, consider the following revenue growth engines that did not exist a decade ago:

• Comcast had de minimis market share in consumer voice in 2004. By the end of 2014, it had 20.5% penetration of all homes passed and had generated a $3.7 billion in revenue. Granted, this revenue stream is a derived number as Comcast does not sell stand-alone voice – and this revenue stream as of Q3 2014 is beginning to shrink – but it has managed to generate good revenues (and terrific incremental margins) over the past decade.

• In 2004, Comcast had no commercial services to speak of. At the end of 2014, they represented a $4 billion revenue stream growing at 21% annually. It does not go unnoticed that business services have overtaken voice as the third-largest revenue stream. In a few years, even with Time Warner Cable’s video revenues, it could become the second largest.

That’s $7.7 billion of revenue, the majority of which did not exist a decade ago. In one instance, Comcast had to develop a product whose quality was equal to or greater than that of an incumbent – including prickly things like E911. Comcast had to enter into thousands of interconnection agreements with large and small (mostly small) providers.

In the case of business services, Comcast had to convince customers that it is credible. Connections to businesses had to be established. Provisioning of nonstandard services had to be accommodated and Ethernet products had to be as good as or better than those offered by the incumbents. And, unlike Time Warner Cable, Comcast has proportionally less cell site backhaul, or large contracts with very long contract terms. Comcast CFO Michael Angelakis disclosed at a recent analyst call that they have a 20 to 25% market share in the small/medium business space. Comcast may have made its entry into business services look easy, but it was far more risky than adding residential voice.

If $7.7 billion in incremental (primarily) organic revenue growth over the past decade is not enough, what about its foresight to add 5 GHz Wi-Fi? This is a gold mine for the company, not only as the “guest provider of choice” for in-home routers but also for outdoor Wi-Fi services should it expand its presence. Angelakis suggested that this might be a reality within a year after the merger ends. With T-Mobile US and Verizon Wireless looking at LTE-Unlicensed, Comcast is extremely well positioned.

There’s plenty to complain about with regard to Comcast. But this is not a stodgy bunch of Philadelphia kings in their counting house counting all of their money, rather they are entrepreneurs with a long history of understanding local topology working to grow bandwidth services to homes and offices. Comcast’s service still leaves a lot to be desired – hopefully a relationship with StepOne will fix that – and video and voice services are in subscriber decline, but the company is not resting on its laurels and simply milking cash cows all day. It is managing portfolios and, at least at the wireline level, outperforming its peers by a mile.

Jim Patterson is CEO of Patterson Advisory Group, a tactical consulting and advisory services firm dedicated to the telecommunications industry. Previously, he was EVP – business development for Infotel Broadband Services Ltd., the 4G service provider for Reliance Industries Ltd. Patterson also co-founded Mobile Symmetry, an identity-focused applications platform for wireless broadband carriers that was acquired by Infotel in 2011. Prior to Mobile Symmetry, Patterson was president – wholesale services for Sprint and has a career that spans over 20 years in telecom and technology. Patterson welcomes your comments at jim@pattersonadvice.com and you can follow him on Twitter @pattersonadvice. Also, check out more columns and insight from Jim Patterson at mysundaybrief.com.

Editor’s Note: The RCR Wireless News Reality Check section is where C-level executives and advisory firms from across the mobile industry share unique insights and experiences.