Last week was already overflowing with earnings news (we will cover AT&T and Verizon Communications earnings in great detail next week), when Bloomberg broke the story last Thursday of the likely Comcast/Time Warner Cable merger demise. CNBC confirmed this rumor on Friday morning, and a few hours later Comcast CEO Brian Roberts went on the CNBC “Squawk Box” set to confirm that the merger was off (full interview here).

Several dozen of you asked me for my thoughts on these events. Well, a sense of merger danger started on Feb. 4, when the Federal Communications Commission redefined what the new broadband standard should be – it is now 25 megabits per second. This rule change served two purposes:

1. For companies like Comcast, it increased their broadband market share because they were the only company offering 25 Mbps or higher service in many areas.

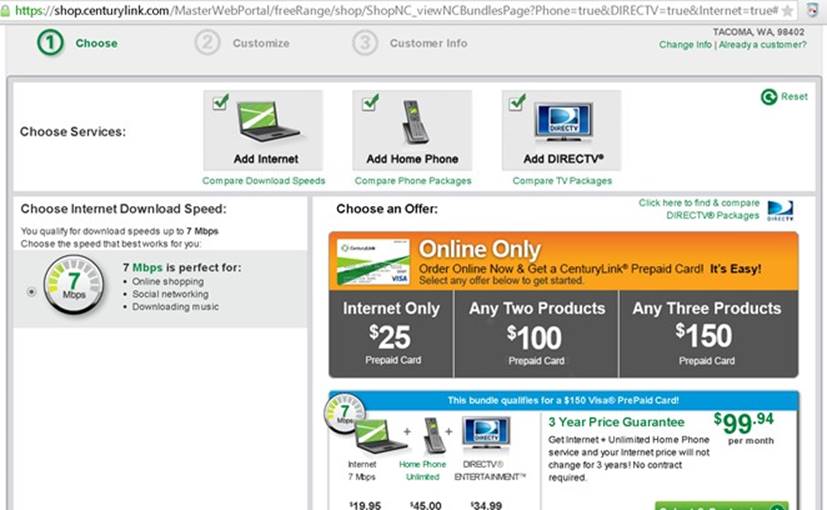

2. Companies like CenturyLink (in Tacoma, Wash., for example) were not counted as broadband providers because they did (and do) not offer residential broadband speeds above 25 Mbps in many parts of their service areas. (For the Jim Patterson in Tacoma, Wash., used in the example shown, his max speed is 7 Mbps, perfect for “online shopping, social networking and downloading music.” No other speed choices are offered by CenturyLink. Comcast Xfinity offers for the same address reached 150 Mbps.) There are hundreds of these examples across the Comcast footprint where it has been a victim of its own success.

This redefinition allowed the media a clear way to highlight Comcast’s either standalone or combined with Time Warner Cable broadband dominance (see Ars Technica article here). Forget the fact that AT&T has just finished a substantial upgrade of its plant, which now covers 57 million homes at speeds up to 75 Mbps, according to their recent earnings call, and is rolling out 1 gigabit per second speeds in 17 markets. On top of this, wireless broadband speeds also are continuing to increase (some analysts contend that the change from 10 Mbps to 25 Mbps was partially chosen to eliminate LTE as an alternative broadband standard). Regardless, the sound bite was clear: Fifty-seven percent of the broadband circuits would be held by one company, and that was too much for the FCC to stomach. Suing to block the merger will do nothing to increase broadband penetration.

Then, California and New York became actively involved in the decision. We wrote about this in a March column entitled “Did California kill the Comcast/Time Warner Cable merger?” On Feb. 13, Comcast and Time Warner Cable received an early “Valentine” from the California Public Utility Commission approving the merger with significant conditions. In April, however, one of the five commissioners, Mike Florio, went so far as to submit a competing 89-page proposal to his fellow commissioners blocking the merger. While it is likely that Comcast could have resolved its differences through the arbitration process , picking up Los Angeles as a result, the question of precedence loomed.

As California flexed its regulatory muscle, New York consistently developed a “wait and see” mode, delaying a decision on the merger six times, most recently on April 20. In many previous mergers, the states followed the lead of the Department of Justice and FCC. California decided to break with that tradition, and New York was positioning itself as the last approval required (and hopefully to get the last concessions).

Finally, there was the Open Internet ruling itself. From the president’s unprecedented move of publicly weighing in on his desires in November (see YouTube address here), to the accusations by FCC Commissioner Ajit Pai of continued “editing” of the actual Report and Order after the FCC vote had been taken (see page 4 of his written testimony here), any future procedure seemed to be subject to the approval of multiple (and historically new) parties. The meaning of “(un)just and (un)reasonable” will play out in the coming quarters as the FCC rewards industry laggards with an easier approval process.

In hindsight, the path to a federal blockade of the merger was fairly clear:

1. Redefine the market to redefine market dominance.

2. Engage key states to coordinate opposition.

3. Elongate the approval process through additional rulemaking, which creates the aura that either/both of the merging parties cannot be trusted.

It makes us wonder what can be approved over the next several years.

What Comcast should do next

Roberts, in the aforementioned interview, stated that it was “time to move on.” Where should they move? Here are three areas they should attack with vigor, and, in my honest opinion, divert share buyback funds to do so:

1. License the Xfinity platform at aggressive rates to any other broadband service provider and become the industry standard. One of the key synergies of the Comcast/Time Warner Cable merger was the extension of the Xfinity platform to TWC’s base. There is no reason why commercial terms should not be able to be struck between TWC and Comcast for this purpose. Or, Comcast could make an even bolder move and spin out the Xfinity development platform into a separate company that would be initially be owned by its MSO peers (with the intent to become a full initial public offering in five years). This would be akin to the spinoff of American Airlines’ reservations system (Sabre) in 2000, which was acquired by two private equity firms in 2007 and rejoined the NASDAQ in 2014.

2. Formalize a common site qualification, provisioning, network monitoring and billing process with TWC, Cox, Charter, Bright House and Cablevision. Provide information to customers about network/circuit performance: real-time packet loss, latency and jitter with automatic service level agreement payment bill credits for performance failures, for example, that AT&T and Verizon will not share today. Provide a contrasting picture to the existing residential legacy – especially for Comcast and TWC – that cable service can lead the industry in products and services. Get the Teleport (TCG – see short Wikipedia summary here) band back together under a standardized umbrella, and use new developments in software-defined networks to create a differentiated service. Leverage outdoor Wi-Fi to reduce enterprise data needs outside of the office. Comcast must take the lead here and challenge the incumbent carriers – Level3, AT&T, Verizon, CenturyLink – to transition their customers from legacy to cloud-based environments even faster than they are doing today. (Verizon’s global enterprise revenue decreased 6% year-over-year. However, without foreign exchange impacts the change would have been 4.5-5%.) It’s going to require a lot of ambassadorship, but value can be created for everyone without destroying existing commercial services margins.

3. Invent a new and secure system for home content storage. At the end of March, Comcast announced that CFO Michael Angelakis will be heading up a new company focused on “investing in and operating growth-oriented companies, both domestically and internationally” (more details in the announcement here). One of the great challenges broadband network providers face is the delivery of large amounts of syndicated content to homes that can be started through a content “seed.” This would enable some part of a movie – the first 15 to 20 minutes; maybe 40 minutes for a particularly popular series that could be subject to server congestion – to be immediately available for the consumer with the rest being transmitted through a secure connection. Given the decreasing costs of portable hard drives (1 terabyte portable hard drives now retail for around$50), entire libraries could be stored. Combine strong underlying technology with easy to use navigation, recommendation and billing, and Comcast could become the recommended choice for binge viewing.

These are three easy-to-solve problems that can run in parallel with bandwidth development, Wi-Fi and customer service initiatives. As we discussed in a previous column, Comcast has generated over $7 billion in organic revenue growth over the last decade from noncore products; residential voice-over-Internet Protocol and commercial services. Their ability to grow wireline revenue in the midst of overall market stagnation is a feat few outside of the cable industry have accomplished (at least not without significant merger and acquisition activity).

Comcast lost the battle, and now it’s time for it to win the war. It starts with customer service recognition and continues with undisputed leadership in technological innovation, specifically the relationship between content delivery and network engineering. Development and business partnerships will be essential, along with well-defined problems for the entrepreneurial community to solve with Comcast’s IT and network units. Finally, it’s essential that “Philadelphia thinking” be replaced with “global excellence” as Comcast sources the best technology minds across the globe.

It’s time to move on. Comcast still beats the telcos, but can it beat Google?

Jim Patterson is CEO of Patterson Advisory Group, a tactical consulting and advisory services firm dedicated to the telecommunications industry. Previously, he was EVP – business development for Infotel Broadband Services Ltd., the 4G service provider for Reliance Industries Ltd. Patterson also co-founded Mobile Symmetry, an identity-focused applications platform for wireless broadband carriers that was acquired by Infotel in 2011. Prior to Mobile Symmetry, Patterson was president – wholesale services for Sprint and has a career that spans over 20 years in telecom and technology. Patterson welcomes your comments at jim@pattersonadvice.com and you can follow him on Twitter @pattersonadvice. Also, check out more columns and insight from Jim Patterson at mysundaybrief.com.

Editor’s Note: The RCR Wireless News Reality Check section is where C-level executives and advisory firms from across the mobile industry share unique insights and experiences.