Turning data into more money: How far can the carriers go?

Outside of the purchase and deployment of new spectrum and networks, there is nothing more important in 2016 to both wireless and wireline providers than monetizing these assets. Two events this month show how carriers are tackling this issue from multiple sides: The initiation of third-party sponsored data (now with increased Verizon Wireless support – see Re/code’s recent article here); and defending this and future innovations against a regulatory climate that is resistent to any model that prioritizes some data over others (see The Hill’s coverage of the D.C. Appeals Court hearing on the Open Internet Order here).

Sponsored data has had a slow and storied start. In February 2012, AT&T’s John Donovan unintentionally made headlines at the Mobile World Congress event when he announced a “feature that we’re hoping to have out sometime next year is the equivalent of 800 numbers that would say, if you take this app, this app will come without any network usage.” This statement generated unfounded concerns within the wireless community that larger applications providers would disproportionately benefit from this feature.

Before discussing the potential risks presented with sponsored data, let’s discuss several areas where the return on investment might make sense:

Sponsored data as a substitute for calling customer service

For example, you are a satellite provider (e.g., Dish Networks) and a customer (who happens to own a smartphone) has just purchased new service. A video entitled “What you can do to make your installation experience fast and easy” is sent to your mobile device via an embedded text link a few days before your installation. Today, a customer viewing that material not on a Wi-Fi network would eat into its high-speed data bucket. For more about this scenario, think about Amazon.com’s “Mayday” application, used for help with selected Kindle tablets, applied to the entire consumer electronics industry.

Sponsored data as a tool to raise awareness before a crisis

For example, you are vacationing on Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, an area at risk for hurricanes at certain times of the year. A storm is approaching and you want to be able to access the latest weather and road conditions. Not only should the local municipality have a keen interest in sponsoring free data during this time (the free data access could be focused on certain towers accessing certain websites or applications), but local businesses and shelters would also be interested in helping out. Today, these type of “event channels” are confined to radio and TV access only, and vacationers might not know each outlet available.

Sponsored data as a commercial incentive

For those of you living under a rock, the latest in a certain movie series opens up next Friday, and no example would be complete without mentioning how exclusive “Star Wars” content would help enhance Subway in-store sales (see their latest TV ad here). For example, if you purchased a 12-inch sub, you might receive the next 15 minutes of high-speed data for free (regardless of whether you used it in the store or in vehicle).

In fact, there are so many examples that could work (Zillow for real estate; AutoTrader for automobiles; even resort sites), the question the industry should be asking is “Why not market this harder?” Restricting content to Wi-Fi (in the link above, Amazon.com admits to limiting “Mayday” to Wi-Fi access only) does not seem to make sense with cost per-megabyte plummeting. While Verizon and AT&T are taking the lead here, it begs the question: “Why are T-Mobile US and Sprint not using sponsored data as a cudgel to challenge their larger competitors?”

Sponsored and prioritized data: where the equation gets trickier

The other major event this month was a several hour hearing in the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals on Dec. 4, where judges David Tatel, Sri Srinivasan and Stephen Williams questioned the government and selected companies and public policy groups on the Federal Communications Commission’s Open Internet Order. Judge Tatel, a President Clinton appointee, is seen as the most influential of the three as he wrote the opinions that overturned the previous two Open Internet Orders (more on his background here and on the overall history of the D.C. Circuit history here).

The hearing was wide ranging and, while many proponents of the Open Internet Order took heart in the tone of some of Judge Tatel’s questions, there were others that clearly called into question the FCC’s motive. (For those of you who need a regulatory primer, section 706 of the 1996 Telecom Act deals with Advanced Telecommunications Services. It’s short and sweet and here’s the Wikipedia link on the “Brand X” case). Here are the Section 706 questions Judge Tatel asked the FCC:

“I ask you a non-Brand X, non-statutory question which is that, it seems to this court’s Verizon decision, the commission seemed headed for regulating under 706, you know, that the commission even called it, the blue print offered by the D.C. Circuit … that’s the commission’s word – not mine. And so what, how do you describe the commission’s reason for abandoning that approach? What’s the policy explanation for that decision? …

“The question is what after the Verizon decision; after this Verizon’s court’s decision, after the commission focused its attention on proceeding under 706? What changed its mind? It couldn’t have been a change in circumstances – right? The circumstances are all essentially the same. What is the crispest answer? … I couldn’t find it in the order.

“What drove the commission to conclude that the authority it had over 706 wasn’t adequate and that it mattered to reclassify? That’s my question. It couldn’t be changed facts; it had to be a different perception of what was happening. What is that?”

Judge Tatel asked these questions because he holds a belief (backed up by his 2009 speech to the Harvard Law School) that federal agencies can sometimes “choose their policy first and then seek to justify its legality.”

While many questions were asked during the proceeding (links to MP3’s of the entire hearing are here), the three provided above, combined with Judge Tatel’s previous speech, seem to indicate those seeking to overturn the Open Internet Order a third time have a shot. It’s not as strong as it was in Judge Tatel’s previous hearings with the FCC on the order, but those who think the FCC has won need to read the speech (and Scott Cleland’s assessment here).

The ability to provide sponsored and prioritized data would change the equation for wireline and wireless communications carriers. Traffic from the “Star Wars”/Subway promotion described above could be prioritized above other traffic served from the associated cell towers, and, as a result, appear to be faster. So could traffic for vacationers in Cape Hatteras (as opposed to competing with their cooped-up children streaming Netflix and Amazon).

All of this screams for the type of legislative action that allows engineers to engineer, marketers to market and commissions to prevent the larger telecom carriers from behaving anti-competitively. While that will not happen until a new administration takes office, we’re hopeful that President Clinton, or President ________, will look at the issue through future-focused lenses.

A combined sponsored and prioritized data business opportunity will be enormous and the upside of a third overturned order to the telecom industry is significant. While the odds are slim that all of the order will be overturned, they are not as low as many of the media reports predict. Regardless of the outcome, monetizing data will be a key strategy for the entire industry in 2016.

Sprint’s speed deficiency: it’s real

I had a lot of comments about last week’s column. Many of you who responded thought there was too much “Sprint-bashing” going on (and this mainly from folks who are/were not Sprint employees). A couple of comments on this – first, there is an inconsistency in the market message concerning Nielsen and RootMetrics data (see New York City chart in last week’s column). Sprint has a faster network at times, but, because Sprint’s Wi-Fi policy manager is much more persistent in offloading their customers to unlicensed (Wi-Fi) spectrum, is it really a fair comparison? In other words, could Sprint’s fast data speeds be based on a smaller (and therefore unequal) sample size with different Wi-Fi usage rates? This question remains unanswered, and, as a result, casts the Sprint Nielsen statements into doubt.

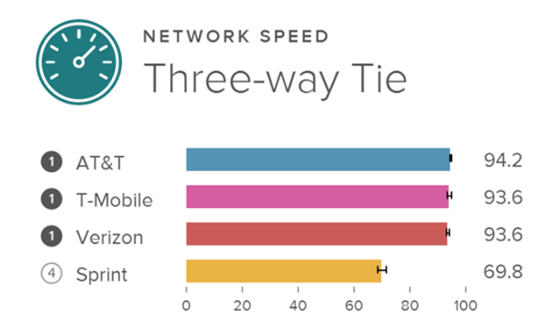

RootMetrics methodology appears to be more evenhanded and is frequently cited by Sprint. Using a Galaxy S6 (carrier aggregation-capable device), they tested Sprint’s network most recently in Worcester, Massachusetts, (Boston is listed as an “LTE Plus” market in this Sprint blog post). Tests were conducted from Nov. 13-17 (Sprint announced LTE Plus on Nov. 17) and included several indoor locations. The result (see nearby picture): a 24-point spread between their data speed score and their peers (all of whom tied for the win with download speeds ranging from 17.8 megabits per second to 19.3 Mbps).

The Worcester result is not an outlier. Other November tests reveal the similar gaps: Columbia, South Carolina (28 pts); Ft Myers, Florida (25 pts); Shreveport, Louisiana (25 pts); New York City (24 pts); Hudson Valley, New York (22 pts); Hartford, Connecticut (19 pts); Washington, D.C. (9 pts); and Detroit (8 pts). Only in my dad’s hometown of Chattanooga, Tennessee, were they even close (3 points). Again, all of these markets were tested in November 2015 with a Samsung Galaxy S6 carrier aggregation-capable device.

Second, last week’s comments were focused on Sprint’s data inconsistency, which matters more than voice or text to a significant minority of today’s wireless population. As for Sprint’s voice and text performance, it’s downright great thanks to Network Vision (part of previous CEO Dan Hesse’s legacy). They will likely win or tie 75 out of RootMetrics’ 125 markets for call quality and a slightly less number (approximately 60) for text quality.

The problem is there’s no value growth in voice and text as Sprint’s recent low-end unlimited product announcement showed ($20 for unlimited voice and text is as good as it’s going to get). In contrast to Sprint’s performance, T-Mobile US has won many speed network tests, but their call drop rate has grown to 2% in a few of the fastest growing markets. Even with this temporary capacity constraint, T-Mobile US should grow approximately 1 million postpaid phone customers in the fourth quarter in large part because of their speedy network. No one is talking about this achievement and Sprint in the same breath.

2016 is Sprint’s year to “fly or die.” It’s all about data speeds, and they can go nowhere but up for many markets.

Jim Patterson is CEO of Patterson Advisory Group, a tactical consulting and advisory services firm dedicated to the telecommunications industry. Previously, he was EVP – business development for Infotel Broadband Services Ltd., the 4G service provider for Reliance Industries Ltd. Patterson also co-founded Mobile Symmetry, an identity-focused applications platform for wireless broadband carriers that was acquired by Infotel in 2011. Prior to Mobile Symmetry, Patterson was president – wholesale services for Sprint and has a career that spans over 20 years in telecom and technology. Patterson welcomes your comments at jim@pattersonadvice.com and you can follow him on Twitter @pattersonadvice. Also, check out more columns and insight from Jim Patterson at mysundaybrief.com.

Editor’s Note: The RCR Wireless News Reality Check section is where C-level executives and advisory firms from across the mobile industry share unique insights and experiences.