SMS engagement rates are over 94%, dwarfing those of most other communication channels. The personal, direct nature of SMS makes text messages nearly impossible to ignore. Think about it: when was the last time you ignored an SMS? You may have 1,136 unread emails and 47 unread Facebook Messenger IMs, but you likely have 0 unread messages in your SMS inbox. It shouldn’t come as a surprise then that an SMS is typically read within 90 seconds of its delivery.

Given that kind of engagement, it follows that SMS is a key channel through which companies send their business-to-consumer (B2C) communication. However, just getting SMS messages delivered can be much harder than one would assume. The complex geo-political history of the modern telecommunications infrastructure has ensured a regulatory landscape that is extremely complicated — both at a country level, as well as at the independent carrier level.

And to think, SMS squats on a control channel that was never intended for person-to-person communication. In fact, that channel is still used for its original purpose: enabling network towers and mobile devices to share status updates. Text messages have to find bandwidth among that machine-to-machine chatter. You could say that each text message delivered is a little victory of human resourcefulness, especially when dealing with the vagaries of different national regulations and network preferences.

To illustrate just how complex the journey of a simple SMS text message is, this article will take you through the gauntlet of challenges global SMS messages have to survive before reaching their destinations. But before we dive into the complicated stuff, let’s start with something simple.

Person-to-person (P2P) messaging

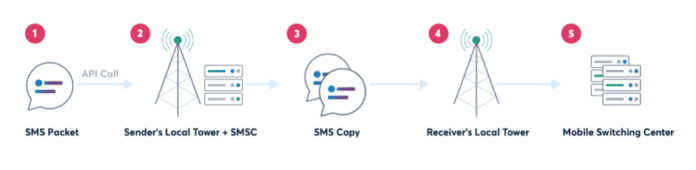

Imagine you’re using a GSM cell phone and you send a text message to your friend. You’re both on the same network and in the same country. In this case, the journey your message takes is pretty straightforward:

1. Your cell phone turns your message into an SMS packet.

2. It then connects to the local tower and sends the SMS packet to the network’s Short Message Service Center (SMSC).

3. The SMSC stores a copy of the message.

4. The SMSC then finds your friend’s number in the network’s list of subscribers, which also tells it which tower your friend’s phone is connected to.

5. The SMSC then hands the message to the mobile equivalent of a central telephone exchange (called the Mobile Switching Center), which handles delivery to your friend’s device.

Assuming your friend’s phone is turned on and has service, the message shows up on their phone. If their phone is turned off, then the SMSC would use its copy of the message to keep retrying.

In the early days of SMS, this was how every message was sent and delivered: without SMS interconnects between mobile networks, messages could be sent to subscribers only on the same network.

The story would be a little different if you were on separate networks or if the phones were CDMA rather than GSM, but the important points here are that:

● SMS uses the network’s control channel; P2P messaging is an afterthought that must vie for bandwidth with the network’s housekeeping messages.

● SMS messages are stored and then forwarded; a copy of your message is kept each time it is handed off from one SMSC to another.

If you’re sending messages to a friend, the impact is little more than the 160-character limit – thanks to the size of the control channel’s data packets – or network oversubscribed messages around midnight on New Year’s Eve. If you want to use SMS commercially, things get a little more complex.

Business SMS messaging

Sending an SMS to your friend is a little like taking a bus to your favorite local mall. Sometimes there’s traffic or the driver is late, but the trip mostly goes as expected. After all, you’re taking one mode of transportation and you’re staying within the same city.

Business messaging is more like global air freight: not only do you need a chunk of infrastructure but you also need to be an expert in local regulations, customs, and individual carrier differences.

Now, let’s make our example a little more interesting.

You run a service from your office in San Francisco and you have customers worldwide. You send daily account balance alerts to your customers via SMS, and some have also opted into receiving special offer alerts by SMS.

Let’s focus on two messages you need to send: one is an account balance alert to a customer in Sao Paolo, Brazil, and the other is a special offer message to someone in Nantes, France.

The physical SMS journey

Much like airplane flights, SMS is all about routing. The route you’d take on a flight from San Francisco to Sao Paolo depends on two considerations:

● the most efficient way of charting that journey

● the airline you choose

If the efficiency of your individual journey were the only consideration, you might take a direct flight heading 6,500 miles to the south-east.

However, no airline offers a direct flight. So, you need to make a connection. For this journey, the airline you choose has more influence over the route you’ll take than the efficiency of your journey. If you fly Delta, then you’d connect in Atlanta or at JFK, whereas if you fly United it’s likely to be Houston.

It’s the same with SMS. There isn’t a single telecoms network covering both San Francisco and Sao Paolo. Instead, your message will be passed from provider to provider until it reaches your customer. And, of course, you’re not sending these messages from your phone but rather through a communications API.

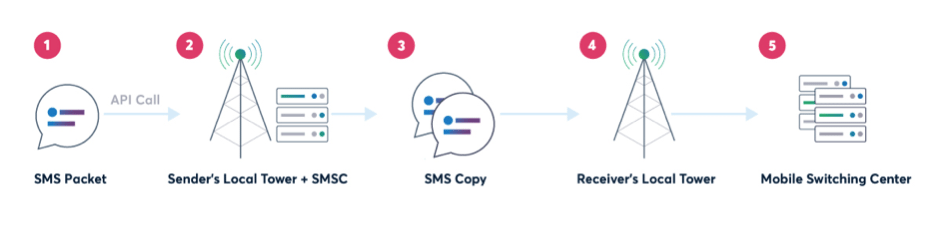

So, the SMS journey looks something like this:

1. Your account management software passes the text and destination of your SMS to your communications provider by way of an API call.

2. The communications provider creates the SMS packet and sends it to their Short Message Service Center.

3. The SMSC stores the SMS and then checks if the recipient is on the provider’s network. In this case, it is not.

4. The provider’s Mobile Switching Center (MSC) checks which of its interconnected providers has the lowest-cost route to the recipient’s network. Depending on the quality of the communications API provider, this could be a direct connection or more likely the first of several hops.

5. The MSC passes your SMS to the next provider, who in turn stores a copy in their SMSC and then forwards it to the next link in the chain.

6. After some hops, the SMS reaches your customer’s mobile network where it hits the SMSC, gets stored, and then is forwarded to their device.

The chances of delivery depend entirely on the quality of your communications provider.

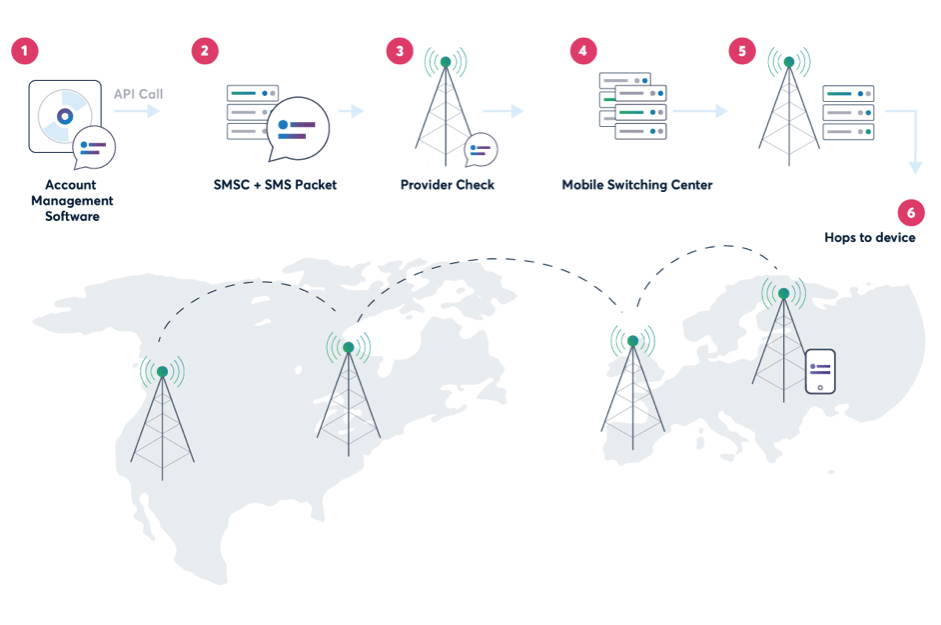

Each SMS hop adds more risk

So, how does provider quality impact the SMS journey? Mostly, it’s about the number of hops it takes to reach the destination network. Thinking back to our flight analogy. Some routes from San Francisco to Sao Paolo will have you stop in Charlotte and Miami before another layover in Rio de Janeiro. Each of those connections presents a risk of something going wrong: your luggage might get lost or a delay could cause you to miss your next connection.

Another flight route has you stop in Mexico, which introduces the complexities of a third country’s customs rules.

It’s just the same with SMS delivery. Each additional hop presents the following risks:

● More processing, meaning more latency.

● One more copy of your message stored on someone else’s servers.

● Another opportunity for something to fail.

● Additional regulations to consider for each network and nation’s border crossed – even if you have no idea the message will touch those places.

Just as with flying, direct routes are less risky.

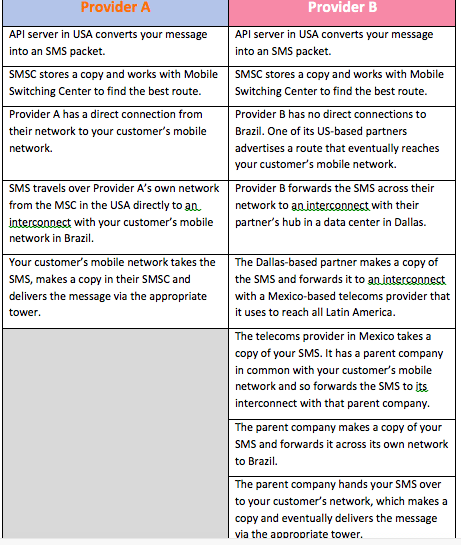

Reducing Hops, Reducing Risk

Brazil is a notoriously difficult destination for international SMS. The more direct your route, the less chance of failure.

In this example, the SMS sent using Provider A will reach the customer first. Each hop introduces more latency, as each SMSC and MSC must work out where to send the SMS next. The deliverability and routing difference we see above is down to one thing: provider B uses least cost routing, where cost is the main concern. Provider A not only has more direct connections but it also monitors the health and efficacy of its different routing options, intelligently selecting the route with best deliverability each time. Nexmo’s patented Adaptive Routing is an example of this type of route optimization solution.

Each hop also reduces your customer’s privacy. Telecoms firms are highly regulated but, nonetheless, with each hop another copy of your SMS gets stored.

Of course, each hop also introduces more risk of something going wrong. In some regulatory jurisdictions, such as Brazil, even a delivery receipt means only that the message reached the network and not the handset.

Regional SMS regulations vary wildly

So, your SMS made it to your customer’s cell phone and they now know their balance. You’re pretty pleased with how much information you’ve crammed into precisely 160 characters.

Then you notice that you’d been billed for two SMS messages rather than one.

It’s not just the routing that can cause unexpected issues: local regulations and norms vary enormously between countries and even between networks in the same country.

Brazil, for example, limits SMS messages to 157 characters. Thankfully, you chose provider A and they could concatenate the two parts of the message. Some providers would deliver the first 157 characters only, losing the last three.

Regional variations are even more important when it comes to the type of content you want to send.

Careful what you send in your message

Remember that you also wanted to send a marketing message to someone in France? Well, as you’re an upstanding business owner, you made sure that the individual opted in to receiving marketing SMS messages from you. By the way, your customer in Brazil also opted in to receive these messages but you have to ignore that opportunity because marketing SMS messages are illegal in Brazil.

This brings up the next obstacle between you and successful SMS delivery. No matter how good the route is between you and the recipient, if you break the rules then your SMS won’t get delivered and you may even face some kind of penalty.

Before you give up on SMS-based customer engagement, note that you can increase the chances of delivery by just choosing a good communications API provider. Knowing what’s allowed in your customer’s country is step one. So, here’s a rundown of what you need to think about to get your marketing message delivered to your customer in France:

● It must come from an alphanumeric ID or shortcode, rather than a phone number.

● STOP au 36179 must appear at the end of the message, or it will be rejected.

● If the message arrives before 8am or after 8pm local time Monday through Saturday, it will be rejected by the three major operators. It’ll be rejected at any time on a Sunday.

● Unicode might work but things like accented characters are likely to be downgraded to their non-accented equivalent.

Similar regulations and oddities exist around the globe. For example, the Optus network in Australia will not concatenate messages over 160 characters but the Telstra network will. Social invitations are not allowed via SMS in Nepal and can result in all your SMS traffic to that country being blocked. Russian operators block almost all messages that contain a URL.

Business SMS Is worth the extra preparation

We love text messaging because we know that it works with just about any mobile device and people respond to it.

When we’re sending messages as individuals, we rarely consider how those messages arrive at their destinations. If SMS delivery is part of how we communicate with customers, though, suddenly the peculiarities of each country’s regulations and network connections affect the efficacy of our own business.

Choosing the right communications API partner can automate much of what you need to think about in terms of delivery and formatting. You don’t need to become expert in SMS delivery; instead, you need to work with a company who can be that expert on your behalf.