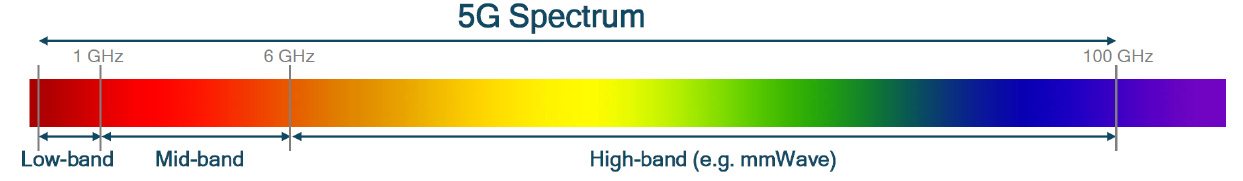

Although much of the dialogue on 5G spectrum in the US has focused on millimeter (mmWave) spectrum, it is not clear whether the mmWave spectrum is suitable for mobile network deployment in the near to mid-term future.

This is exactly why Verizon is concentrating on the Fixed Wireless Access use case in order to develop an ecosystem of vendors to advance mmWave technology and showcase the building blocks that will ultimately be necessary for the commercial deployment of mobile 5G. The array of technologies that need to be developed, miniaturized and optimized include antenna technology, RF front-end circuits, including mmWave power amplifiers and filters, as well as the associated PHY and MAC digital circuitry capable of utilizing mmWave for the over-the-air interface. All this has to ultimately be developed in low power semiconductor technology for integration in handheld, battery operated smartphones.

For now, the 5G Fixed Wireless Access use case is an ideal application to enable the industry to develop and test many of the piece-parts that will ultimately be integrated into smartphones. Most industry analysts and observers will agree that it is unlikely to see wwWave 5G technology integrated into smartphones in the next two years. Low-band wireless signals travel further and penetrate obstacles like buildings better than the mid-band and high-band spectrum. But if the Mobile 5G promise is to be met by the 2020 timeframe, sub-6 GHz spectrum will be necessary.

In a new report, Spectrum Strategies for 5G, Wireless 20/20 examines the state of the US sub-6 GHz spectrum availability as it applies to 5G Mobile deployments. By asking “What spectrum bands will US operators use for Mobile 5G?” we examine not only the current spectrum holdings of the top 4 US mobile operators, but also the potential availability of suitable spectrum for mobile 5G deployment in the USA.

We consider a spectrum band to be suitable for 5G deployment if it consists of a minimum of 100 MHz of bandwidth because to deliver speeds close to 1 Gbps, 100 MHz will be needed if an efficient modulation scheme is used that produced 10bits/Hz, assuming TDD technology. According to Joan Marsh, AT&T’s VP of Regulatory Affairs, ideally 200 MHz blocks are needed for favorable 5G deployments and maximize the number of blocks available for auction. If FDD technology is used, this would enable 2×100 MHz of spectrum in order to deliver 1Gbps downlink speeds. There is always an opportunity to use asymmetrical downlink vs. uplink spectrum bandwidth (for example, by allocating 100 MHz for uplink and 40 MHz for downlink). There is also the option of combining two separate spectrum bands, where one is used for DL and the other is used for UL (for example, AWS use case of 1700/2100 MHz for UL/DL).

By this definition, neither AT&T nor Verizon nor T-Mobile currently controls sufficient sub-6 GHz spectrum that is suitable for mobile 5G deployment. Only Sprint has the 100 MHz of bandwidth in the 2.5 GHz spectrum band that could support 5G deployment with user downlink speeds that could deliver 1 Gbps service. T-Mobile participated in the 600 MHz auction and was able to secure 31 MHz of this low-band spectrum in many markets nationwide. The total bandwidth available in the 600 MHz LTE Band 71 is 70 MHz, and T-Mobile obtained an average of 31 MHz, clearly not enough by itself for mobile 5G deployment.

US Mobile operators have several options when it comes to assigning sub-6 GHz spectrum for mobile 5G. These include:

- Re-farm spectrum from 2G and 3G and use channel aggregation to allocate 100 MHz of spectrum for 5G.

- Lobby the FCC to open 3.5 GHz spectrum for 5G.

- Lobby the FCC for finding 4 GHz or 6 GHz spectrum that could be used for 5G.

- Work with existing 2.5 GHz spectrum holders in order to open up the additional 2.6 GHz spectrum that is not held by Sprint.

- Partner with current holders of virgin sub 6 GHz spectrum in the USA (i.e., DISH Networks) and combine their AWS spectrum with existing AWS spectrum to aggregate the necessary 100 MHz for Mobile 5G.

For Sprint, the most logical approach would be option D, where Sprint would potentially consider working with other 2.5 GHz owners and essentially control a contiguous 200 MHz of spectrum from 2496 – 2590 MHz in the USA. Sprint and other educational licensees are already asking the FCC to extend the geographic coverage of 2.5 GHz EBS spectrum to county boundaries and issue additional licenses in existing white spaces.

For Verizon, the most logical approach would be option E, where it could partner with DISH and combine DISH’s AWS spectrum with its own and thereby control a large chunk of 1700 / 2100 spectrum for 5G.

For AT&T, it could enter a bidding war with Verizon over DISH’s spectrum and consider lobbying the FCC to open new 5G spectrum (which could be 3.5 GHz, 4 GHz or 6 GHz).

For T-Mobile, it could increase its effort to lobby the FCC to assign the 3.5 GHz spectrum band for 5G. If successful, this will give T-Mobile a shot at acquiring new, and relatively unencumbered spectrum suitable for 5G. Otherwise, it could join AT&T in lobbying for new 5G spectrum in the 4 GHz or 6 GHz bands.

Because of the unclear path for sub-6 GHz spectrum suitable for mobile 5G deployment, the US is lagging other leaders in the field of mobile 5G. Focusing solely on mmWave as the path to mobile 5G has many challenges. China and the EU have recognized the benefits of allocating sub-6 GHz 5G spectrum and are focusing on the 3.5 GHz spectrum band. Canada has the opportunity to designate the 3.5 GHz spectrum for 5G since most of that spectrum is unused in metro markets.

If the FCC is unable to pave the way to make sufficient low band spectrum available for 5G, then perhaps US mobile operators could consider joining forces by sharing 5G spectrum in order to build mobile 5G networks. The question of whether a country needs four separate nationwide 5G mobile networks is more valid today in light of the limited availability of low- and mid-band spectrum. It should not take long for operators to realize that it is more economical to build shared 5G mobile networks than four separate 5G networks each needing separate spectrum.

In our new report, Spectrum Strategies for 5G, Wireless 2020 argues that If North America wants to lead the World in the 5G Era, this is a critical time to plan and allocate harmonized 5G spectrum in low, mid and high bands.