Should CBRS rules be designed for carriers or for everyone else?

The 3.5 GHz band is seen globally as a 5G band and, in the U.S., as a key to providing private LTE as well as 5G. As the U.S. Federal Communications Commission considers rules to allow incumbent users of the 3.5 GHz Citizens Broadband Radio Service (CBRS) band, telecom industry stakeholders are pressing the FCC to finalize rules governing shared access to the spectrum in a way that protects incumbent users while facilitating operator investment.

T-Mobile US has been particularly vocal in its calls on the FCC to take action on not only CBRS rules, but also on auctioning licenses for millimeter wave spectrum in the 24 GHz, 28 GHz, 37 GHz, 39 GHz and 47 GHz bands.

In a Feb. 8 filing with the FCC, T-Mobile US’ Steve Sharkey, vice president of government affairs, technology and engineering policy, made the case that regulatory action related to the 3.5 GHz band will “help preserve U.S. leadership in the race to deploy 5G.”

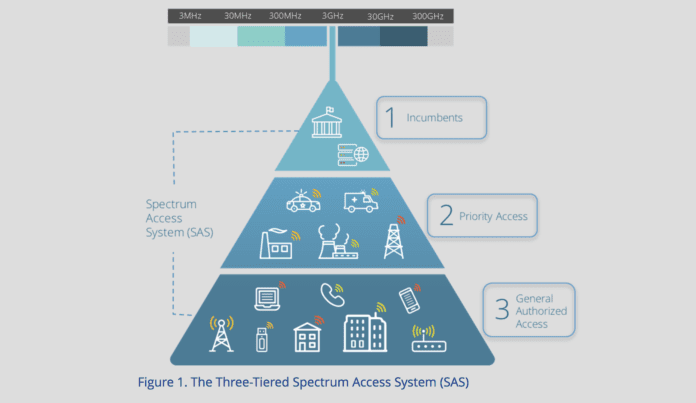

As it stands, the FCC is considering a three-tiered approach to CBRS spectrum allocation. Tier 1 will support incumbent users, which includes the Department of Defense and fixed satellite service providers. Tier 2, the contested space, will be licensed for commercial use. Tier 3 is generally available to users who can operate in the spectrum without impacting the higher tiers.

As it relates to Tier 2, Sharkey says T-Mobile wants 10-year licenses that aren’t assigned based on geographic tracts established in the U.S. Census. To the licensure period, he wrote, “10-year license terms are necessary to permit entities to take all the steps required – developing and optimizing technology, securing antenna siting – and necessary to provide a robust service. A full license term will best allow providers in rural, urban, small or large market to succeed.” To the geographic area piece, Sharkey wrote, “The use of census tracts will materially impair licensees’ ability to use their authorized spectrum–and the ability of spectrum access system…administrators to manage the spectrum for both licensed and GAA users–because of the number of geographic area borders created.”

High-band millimeter wave spectrum–the 24 GHz, 28 GHz, 39 GHz, etc…bands–are essential to delivering the multi-gigabit-per-second throughput 5G promises. T-Mobile wants all of that spectrum, some of which is already licensed, to be auctioned together to support a “more robust and competitive auction. In contrast, auctioning only the 28 GHz and 37/39 GHz bands now will further entrench the precise entities that have already established a strong presence in the band and permit limited opportunities for new entrants to the millimeter wave bands. This will stifle competition.”

A firm timeline for availability of 3.5 GHz and millimeter wave spectrum is imperative to fostering operator infrastructure investment, Nokia representatives recently communicated to FCC Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel. Based on a Feb. 1 filing with the FCC that reflects an earlier conversation with Rosenworcel, Nokia “urged that the commission establish a timeline for auctioning mid-band and [millimeter wave] spectrum bands to add certainty for future 5G builds.” Like T-Mobile, Nokia hit on the importance of this spectrum in “U.S. global competitiveness.”

On the other side of the issue, there are a number of ecosystem stakeholders that want the FCC to keep the proposed three-year licensure period for Tier 2 licenses, rather than move toward a 10-year period.

From a Jan. 30 letter signed by more than 170 ecosystem stakeholders including HPE, Baicells and a bevy of WISPs, a 10-year licensure period not attached to census tracts “would create the same prohibitively costly system that exists in other, traditionally licensed bands, and would exclude the non-traditional, innovative actors that have been so interested in the band since its inception. In fact, changes like those contemplated would strand the investments that many of us have already made in the band, which were made in reliance on the current rules, to serve targeted communities and use cases that do not require large areas or long license terms. Not only would this be disastrous for these companies, but it would certainly forestall future cutting-edge investments, including in 5G technology and the [industrial internet of things], and preclude access by any users, other than the largest national carriers.”