National security issues have come to the fore with 5G equipment vendor selection for network deployments and upcoming service launches over the next year or two. Cyber security threats of many kinds are real and significant; but debate about this has become deeply entwined with those on international trade including sanctions busting, industrial policy and protectionism. There is a perceived threat from China including Huawei on all these fronts.

We certainly need to be increasingly vigilant in securing our cellular networks. Expanding capabilities in 5G including in consumer and industrial IoT also increase the scope for malicious actions. These could be catastrophic financially and in terms of national security. But merely blacklisting selected companies based on nationality and alleged obligations to leak private and confidential information to foreign authorities could lull us into a false sense of security.

Uncertainties about such companies, particularly where they have already been selected as suppliers, as is the case in many European nations, are also delaying 5G deployment. I wrote in RCR recently about how Europe is already behind in 5G due to regulatory constraints and delays in spectrum licensing. Sentiments I heard echoed by leading speakers at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona recently.

Eye of the storm

At the centre of all this and in a US-China trade war, Huawei is the largest technology company in 5G because it has the biggest market share in networks, while also being the third-largest smartphone seller and self-supplying most of its modem chips for these. However, its prowess is somewhat exaggerated as it is commonly misreported of late that Huawei has overtaken all others to become the most advanced company in 5G. Companies including Ericsson, Nokia and Qualcomm are less diversified than Huawei, but have longer and stronger track records as innovators and developers including 5G’s technological foundations. Nevertheless, Huawei’s heft, together with concerns about it flouting export bans to Iran and Chinese industrial policy including expropriation of intellectual property from companies foreign to China have made Huawei a target for retaliation. One year ago, ZTE was shut down for a couple of months for breaking export sanctions, with an embargo on it receiving the vital US-made components it needs in its manufactures.

Some maintain that concerns about security are overblown, and that it is unfair to preclude Huawei, or any other company, based on nationality and purported subservience to its government or the communist party without clear supporting evidence. The US government is firmly set against Huawei equipment being used by its major national operators including AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile and Verizon. Other developed nations including Australia and New Zealand have also indicated that purchases of Huawei equipment would be blocked, though Huawei contests whether it has been banned outright. Elsewhere, for example, Jeremey Fleming, the head of the UK’s communications intelligence agency, GCHQ, recently said in a speech that a supplier’s country of origin should not lead to automatic bans. German authorities are also reluctant to impose an outright ban.

From industrial policy to security policies

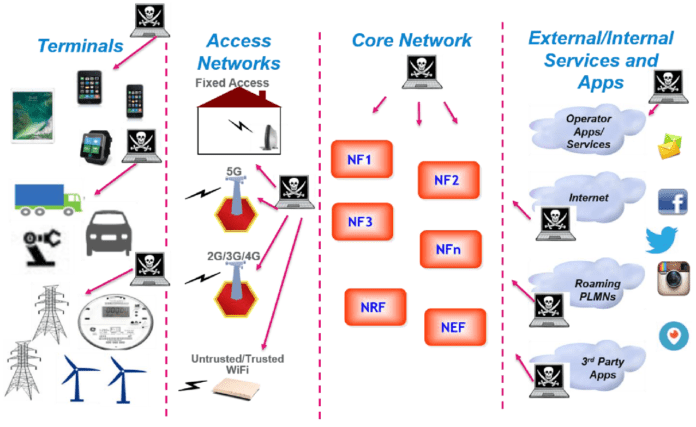

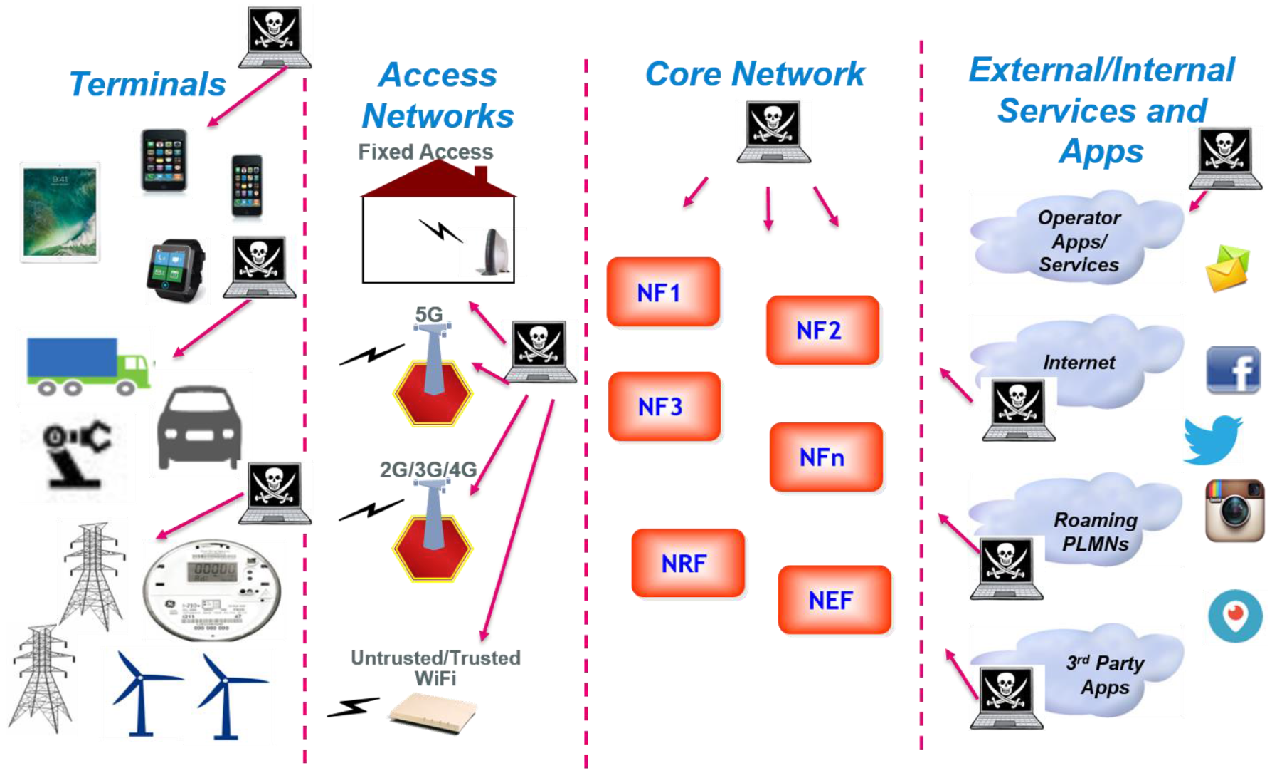

While seeking assurances and testing to ensure that confidential customer information cannot be read and passed — for example, using “back door” access—from equipment suppliers to foreign governments, multifarious security threats come from many different directions, can appear in various places and be perpetrated by numerous different actors. A recent white paper on 5G security from 5G Americas systematically identifies various threats, including those that seek to bid-down connections to less secure 4G and 3 G connections. 5G threats can emerge in IoT, in terminal equipment, in the RAN (for example with the insertion of rogue base stations), in the core network, in network slicing, in NFV and SDN, and in interworking and roaming. While suppliers of RAN and core networking equipment have opportunities for nefarious actions, so do third-party software suppliers, rogue employees and contractors, as well as others who might find ways of hacking in from the outside.

The 5G security threat landscape

Complete testing

How should security in 5G network equipment supply be tested to minimize the risks of incursion and harm? While the GSMA representing 800 operators supports the concept of implementing a testing regime to avoid outright bans on specific vendors, there is concern that this would be a costly burden, cause significant delays and there are differences of opinion on what would be effective. Lab testing equipment, off-line, by organizations such as GCHQ would have significant limitations. In a world of DevOps, where software configurations are continuously being changed, new security threats can also be introduced concurrently. More complete testing would need to be done regularly on live networks. Consequently, security agencies, such as GCHQ, would need deep, exhaustive and continuous access — through front doors or back doors —at least to their national operators’ networks. Lawful intercept provisions already provide some of that enabling law enforcement to listen in where criminal and terrorist activities are suspected.