It’s been a busy time for 5G launches. It started with Verizon and AT&T towards the end of 2018 followed by a flurry of recent announcements from Korea, China and more in the US. So, are we there yet? Is the long car ride over? Yes and no.

There are differences between each announcement and differences yet to come.

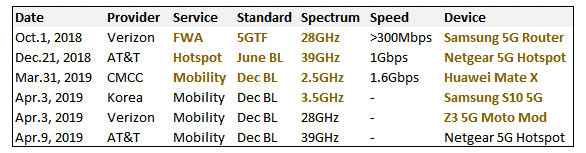

Verizon’s initial launch was with a fixed wireless service based on a pre-3GPP standard called 5GTF, at 28GHz with a Samsung device. AT&T’s initial launch was based on the June 2018 version (“baseline”) of the 3GPP standard, at 39GHz with a Netgear Hotspot device. The more recent launches are based on the December baseline of 3GPP and support full mobility using different frequencies and devices. One could view these as a series of necessary and supporting steps towards large scale global commercialization. Also, users should not be concerned as providers are highly likely to provide either software or free of charge upgrades in those few cases where required.

Here’s the secret decoder ring with world firsts highlighted (BL=baseline).

[Note: We expect imminent T-Mobile deployments in mmWave and Sprint in 2.5GHz.]

The optimist would say 5G has arrived, the pessimist would say these are marketing misdemeanors and the procrastinator would say I’ll decide when I see it in my neighborhood. Deeper thoughts are required to get to the answer.

Let’s start with spectrum. Millimeter wave (mmWave) frequencies are limited in propagation and thus are more likely to be deployed in locations with high capacity demands; think, dense urban corridors or large venues. Mid-band frequencies, like 2.5GHz and 3.5GHz, propagate better and are well suited for larger coverage areas. Finally, as one would expect, lower frequencies propagate the furthest and are likely to be the foundation for nationwide deployments. This is illustrated below.

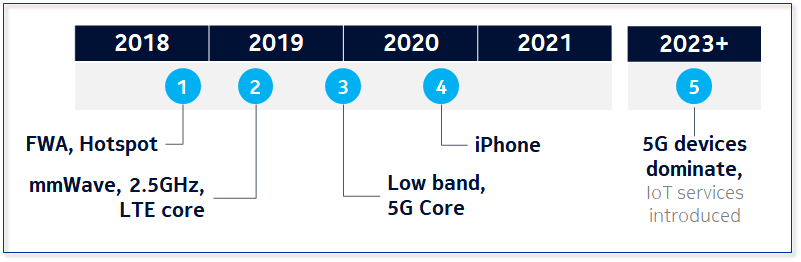

Now consider Verizon, AT&T and T-Mobile. For simplicity, let’s call them the Triad. The Triad has plans for both mmWave and low band deployments, with the latter more towards 2020. That means we can imagine relatively localized deployments in 2019 with broader geographical coverage in 2020.

Next up are devices. Today’s devices are based on 2 Qualcomm chipsets, one servicing LTE (855) and one servicing 5G (X50). The X50, for the U.S., is limited to mmWave, 2.5GHz (used by Sprint) and an LTE core network. Towards the latter part of 2019, Qualcomm will release the X55 chip, supporting both LTE and 5G in low, mid, and high bands, and standalone 5G core networks.

That means that if you buy a device today, it will support the Triad’s mmWave and Sprint’s 2.5GHz 5G deployments, but not future low band 5G deployments and not any unique 5G core network related services. Also, single chip devices are generally better than dual chip devices in terms of size and battery life. For the average user though these improvements will be irrelevant for the near to mid-term.

Then there’s Apple. With about 50% market share in the US, one cannot deny the importance of the iPhone’s support for 5G when thinking about widespread adoption. There has been no public announcement regarding a delivery time, and thus I have no knowledge about their plans, but for the purpose of this article, let’s assume September 2020 as has been reported by some media.

Putting all this together, with an annual upgrade rate of about 20% in the U.S. and taking into account that initial 5G devices will be towards the higher end, thus limiting the speed of uptake, one can fairly easily predict that it will take until about 2023 for the number of 5G smartphone devices to overtake the number of 4G devices.

But what about all those fancy 5G services we see promoted so often like autonomous driving, remote surgery, smart factories, gaming and so on? Many of those can be launched with LTE and evolve to 5G when appropriate. However, it is true that some will require 5G due to its inherent support of low latency, reliability, faster speeds and application specific standardization work. As a rule of thumb, low cost IoT chipsets generally come after a technology has matured somewhat, as was the case in 2G, 3G and 4G. We imagine that 5G will be similar. It’s anyone’s guess when that might be, but please allow me to peg it in 2023 for now. However, note that low cost devices do not preclude proof of concept systems being developed now, and indeed, that is the case.

Now, back to the original question, “Are we there yet?” I would suggest there are five markers that help address that question as shown below.

Clearly, there are many answers. For early adopters, we are there now for Android devices and will be there towards 4Q20 for iPhone aficionados. For people living outside dense urban corridors, service is more likely in 2020-2022. For those looking at the start of LTE ramp down, we are likely more towards 2023. Finally, for IoT application developers and vertical industries, proof of concept 5G systems are being developed now but larger scale deployments are more likely in a few years.

So certainly, for some, we are there now.