Note this is a serialised version of an editorial report, called LPWA connectivity in IoT – who is winning what?’. It is continued from a previous instalment, which can be found here. The full report, including additional content, is available for download here.

The contest is liable to turn into a scuffle at any moment, and here it comes: blows are quickly traded. Sigfox is compelled to defend its payload limit, of 12 bytes per uplink message. It is plenty, argues Sigfox operator WND: location data takes six bytes, for example; a temperature reading takes a couple, at most; notification that a door has opened / closed is just one byte.

“These are small amounts, but it becomes an abstraction layer when aggregated across many devices – and you start to be able to make really good decisions. Businesses want to be more effective and economical. They need that sensor data to achieve that, but they need it in the right volume, and at the right price,” says Clarke.

Any more than 12 bytes can be scheduled over multiple transfers – up to 140 per day – and data is only any good if it can be sorted and used. Enterprises have learned data harvesting should be managed, and stopped from flooding operations. “Organisations are more sensible about the data they need. You don’t need much – just enough to give that pinpoint information,” says Clarke.

Krishnan adds: “It is too simplistic to say 12 bytes is a fit-and-forget solution. Data requirements for smart meters are small. Street lighting, you’re looking at six to eight different metrics – they transmit about 128 bytes per day. With Sigfox, you can break it down into multiple index reports – a dozen transmissions is 144 bytes per day.”

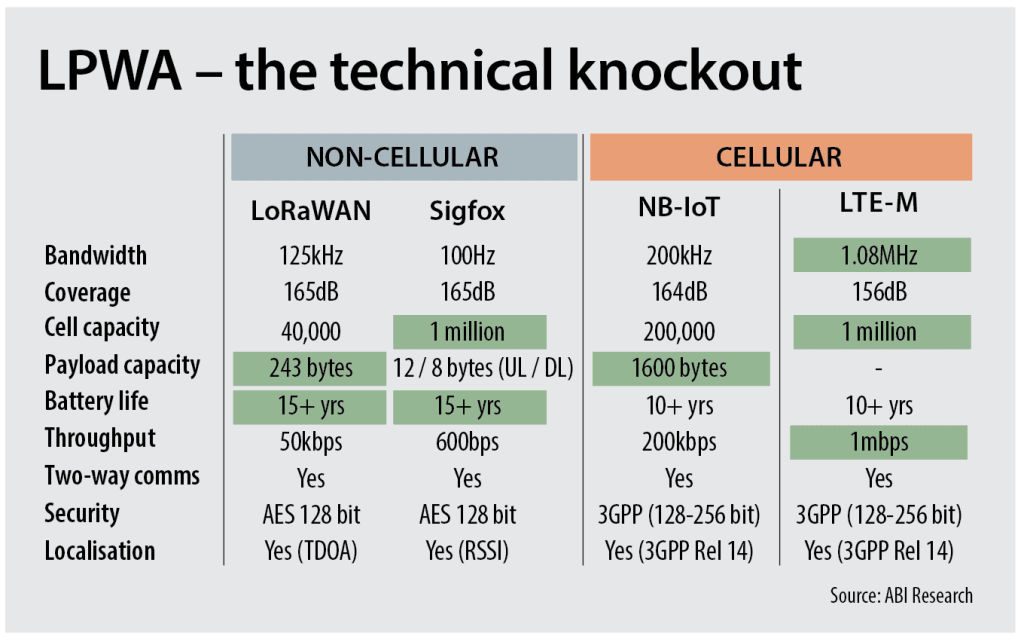

Of course, multiple missives drain the battery faster. With NB-IoT and LoRaWAN, a single message will do. And analytics tools are becoming ever-more sophisticated, and volumes are only going one way. Surely it makes sense to have the capacity in the bag, to cater for future solutions as well? And who wants to do the maths, anyway – to divide data payloads into multiple deliveries?

“I’m sure this matters, yes: more is better, just like in the consumer world. But it doesn’t translate directly with enterprise applications,” says Krishnan.

He notes UK firm Telensa, with the largest footprint of smart street-lights anywhere in the world, uses its own Sigfox-like ultra narrowband (UNB) tech – which accounts for a decent wedge of the ‘other’ non-cellular LPWA tech in the market today (which has a 71 per cent market share, according to ABI’s figures).

“One argument says enterprises want more power, more bandwidth, and faster networks; the other says they want to keep costs down. No technology will do everything, and the market doesn’t want to be tied to a single solution. Application requirements are varied. Enterprises want flexibility.”

But the blows fly in the blue corner, like between siblings. Their models are fundamentally asymmetrical: Sigfox is closed at network level and LoRa is closed at chip level. Sigfox controls the network layer. Semtech is the sole supplier of LoRa chipsets. But there are technical points, as well, and Sigfox is on the ropes.

The French firm has forever fielded charges about two-way communications, as a means to open up a broader range of applications. Quant, as agitator in chief, perceives its glass jaw, and lets fly. “You need an aperture, like on a camera, that can go from very small data rates up to at least modest data rates,” he says.

“Yes, LTE-M offers higher rates, but LoRaWAN, NB-IoT, and LTE-M all have that aperture, which gives a broad set of use cases – so you’re not just typecast into one role.”

But Sigfox claims its chipsets have supported bi-directional communications for years, albeit with an eight-byte payload limit on the return, and downlink messages limited for four per day – meaning acknowledgment of each uplink message is not supported.

TECHNICAL KICKING

Maybe Sigfox gets a kicking from its peers because it offers the most technically limited sensor connectivity, beaten on every count. Does Quant think it is the best choice for anything, actually? “Yes, it’s the best choice for a business model where I pay as I earn, and the asset I’m connecting is a non-mission critical, cheap, low-value sensor.”

But does that model not reflect most of the low-lying IoT market, as it is today? “You’re dead right. It is the high runner, the killer app – a low-value, non mission-critical, almost-throwaway sensor, which is super cheap,” he says.

“The difference is most everybody that owns that type of sensor wants to capitalise the investment at the outset, rather than pay month after month for each sensor, for the life of the product. If you’re paid every month for the data, you can afford to pay monthly. But If you’re connecting a $20 hand sanitiser in a bathroom, you really want an upfront expense, amortised over the life of the product.”

The counter argument is that, with gazillions of hand sanitisers, you can save more on site visits and refills than you spend on connectivity, and managing a private network is not worth the hassle and expense. That is the WND line. “The cost to the end-user is pence per-month, per-device,” says Harris, back in the peanut game.

“We need scale – millions of connections – to make money. Our subscriptions get cheaper as they multiply. The end user, in many cases, doesn’t want to buy gateways and manage networks. They’re not in that game. There’s a cost involved in looking after a network. These things don’t just run by themselves.”

The LoRaWAN collective might shrug at this, and point out it offers both public and private networks, available variously on op-ex and cap-ex terms. Radio interference is another sore point, from a hurl of fists. Sigfox uses a BPSK frequency-shift keying (FSK) modulation. “It’s super easy to smother it out with white noise,” says Quant.

But Harris says Sigfox “punches through the noise floor” in the ISM band, with each message transmitted three times over different channels.

LoRa is a physical layer technology that modulates the signals in the sub-GHz ISM band using a proprietary spread spectrum technique. Two-way communication is provided by chirp spread spectrum (CSS) modulation, which spreads a narrowband signal over wider bandwidth. The resulting signal is supposed to have low noise levels, and high resilience to interference. Harris says LoRaWAN messages take longer to get through, and are more vulnerable as the noise floor rises with ‘chatter’.

NB-IoT, deployed by cellular operators in their guard-bands, is caught up in the melee, too. “The guard bands are there for a reason. They are to stop the roll-off in 47dB output power of base stations leading into the channel next to them,” comments Quant. The signal-to-noise ratio for NB-IoT is higher than advertised, he suggests; only private NB-IoT deployments (see box, page 17) can really claim 180 kHz bandwidth and 60 Kbps throughput.

But Skipper at Vodafone repeats the mantra about licensed cellular bringing scale and reliability. “In the end, the debate about whether technology X is better than technology Y comes down to what you’re trying to achieve, and how long you want to achieve it for. Those are the drivers. And because you’re running in licensed spectrum, you get the scale and certainty an operator brings.”

TECHNICAL DRAW

Which brings us about full-circle, as the bell sounds. The forecasts say the market will explode – to 3.56 billion LPWA connections by 2026, according to ABI. Much of this growth will be in asset tracking, attached to a range of applications in the broad supply-chain industry. “There are dozens of different sorts of asset tracking,” says Krishnan.

And the idea, actually, that our four protagonists are pugilists in the same ring is wrongheaded, despite the bad blood between them. If we extract a new LPWA pyramid showing volume against value, out of our old IoT pyramid, we see LTE-M, NB-IoT, LoRaWAN, and Sigfox occupy different planes, in descending order. In time, the pyramid shape mutates, perhaps, as connection volumes settle between four technologies – ABI’s 2026 figures would draw it as an hour-glass.

Sigfox’s story is the best illustration of this. Hebbelynck says Proximus hardly comes across Sigfox anymore, as it goes about connecting utilities and cities to its LoRaWAN and NB-IoT networks. “It’s still there, which is good, because the market is struggling for maturity, and we’re spending lots of time convincing customers IoT helps with their digital transformation. But we see less competition from Sigfox than before.”

But there is a reason for this. Sigfox has quit the ring, and gone down a weight division. ABI has asset tracking growing as a proportion of Sigfox’s LPWA connections from nine per cent to 68 per cent in the period to 2026, as it goes after a brand new segment looking for super-cheap narrowband trackers. Cellular backup connections, plus everything in metering and cities, will comprise just 32 per cent of its base in 2026.

Most of the Sigfox-bashing has come from the operator set, actually, and not the LoRaWAN community, says Sigfox. “They see us as a threat, and it’s wrong,” says Jay. “There has been a lot of noise in the last year – that Sigfox will die, that it will never work, that a small French company can’t change the IoT space.”

She goes on: “They have to lose this emotional response – that mobile operators are the only ones, in a monopolistic market, able to sell connectivity. We are not a threat, and they are only now starting to realise just how complimentary we are.”

Sigfox is hardly crossing-over anymore with LoRaWAN and NB-IoT – and, as we have heard, cellular operators are pushing for large-scale, high-value corporate contracts at the top of the pyramid, as they find them. “The use case dictates the technology, and not the other way around,” comments Jay.

The bout is finished, says Krishnan. “You’ll never find one technology to address every application. It comes down to the business case, more than the use case. That’s where the value is, and what many of them are still missing.” The LPWA market is being multiplied outwards. Anyone throwing jabs in the ring is just boxing shadows.

A full version of this article, including additional content, is available for download here.