Greetings from Chicago, Illinois (where the pre-winter winds were tame), and Davidson, North Carolina (where it really feels like winter even though it’s mid-November). This week’s TSB is less about the week’s events and more about strategy fundamentals. Next week’s edition will focus on several “What if?” questions posed by this week’s article, and we will follow it up with a Thanksgiving edition retrospective review of Dr. Tim Wu’s The Master Switch.

The long, long run

We have been doing a lot of reading and thinking recently about how telecommunications and technology have evolved, the role of the government in protecting free and fair commerce, and disintermediation of traditional communications functions primarily through applications.

Through our research, we have established several foundations of long-term success in the telecommunications industry, which include:

1. Purchase, deployment, and maintenance/upgrade of long-lived assets. These include but are not limited to items such as fiber, spectrum, land/building (including sale/leasebacks of such), and other long-term leases. Regardless of the type of communications service offered, the greatest potential long-run incremental costs begin with assets like these.

When Verizon discusses their out-of-region 5G-based fiber deployments (4,500 in-metro route miles per quarter for multiple quarters) as well as their willingness to lease/ rent to others, that’s a current example of the deployment of long-lived assets. (When Verizon paid $1.8 billion for the fiber and spectrum of XO Communications in 2016, it was a bet on the long-term value of the asset and not XO’s previous annual or quarterly earnings).

All long-lived assets rely at least partly on location. Fiber, land, building and similar assets cannot easily be moved. Building or buying assets in the right places matters – a lot. Local exchange end offices that were in the right places when they were built in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s may not be in the right places today. The same could be said of fiber networks and Points of Presence (PoPs) deployed by MCI and Sprint in the 1980s and 1990s (AT&T’s fiber upgrades came 10-20 years later). The location of these assets (e.g., locating a PoP at a major point in the city versus a village bus stop) is critical to product competitiveness. The less moveable the asset, the higher importance to get the initial investment decision, including location, correct.

It’s important to note that things like voice switching and eNodeB (tower switching) are not long-term assets. They are important investment decisions but can be moved (somewhat) more easily than fiber PoPs and tower lease locations.

Spectrum is more fungible but is still local (Just ask T-Mobile as they are in the middle of negotiating a lease for Dish’s AWS spectrum in New York City). And spectrum bands have different values at different times: just ask Teligent (24 GHz spectrum), Nextlink (28 GHz) and Winstar (28 and 39 GHz).

Bottom line: With few exceptions, sustainable telecommunications strategies begin with long-lived assets. Get these selections right, and subsequent decisions are easier. Cut corners on long-term assets, and future determinations become a lot harder. Match the deliberation level to the expected life of the asset.

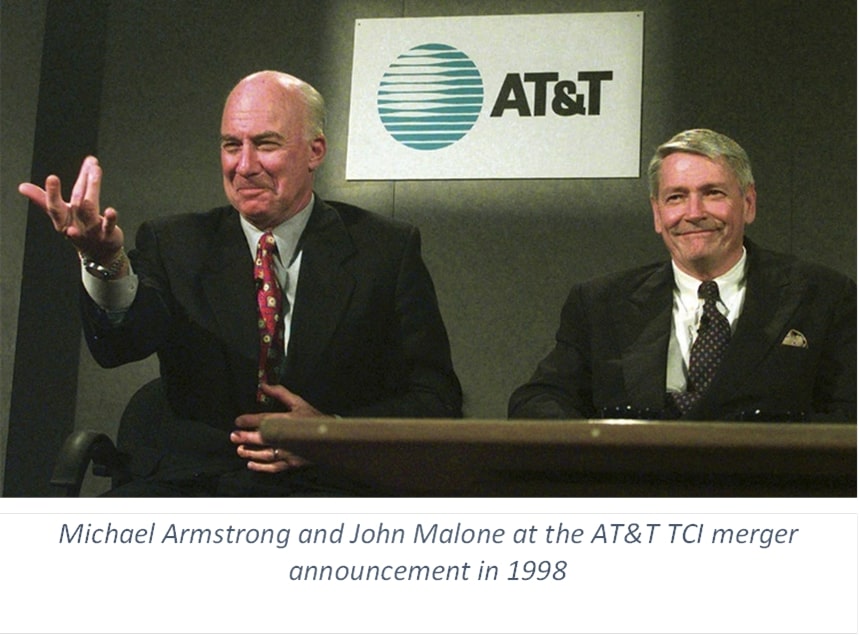

2. Business and technology strategy which drives network equipment (and service) performance. This super-critical element is often ignored under the pressure of a quarterly earning focus. For example, AT&T purchased cable giant TCI in 1998 for $55 billion. AT&T ended up spending over $105 billion on its cable assets, only to sell them to Comcast a few years later for $47.5 billion (news release here – that was a mere 17 years ago almost to the day). This acquisition was not simply driven by scale (although it was an important consideration), but because AT&T saw value from TCI’s cable plant.

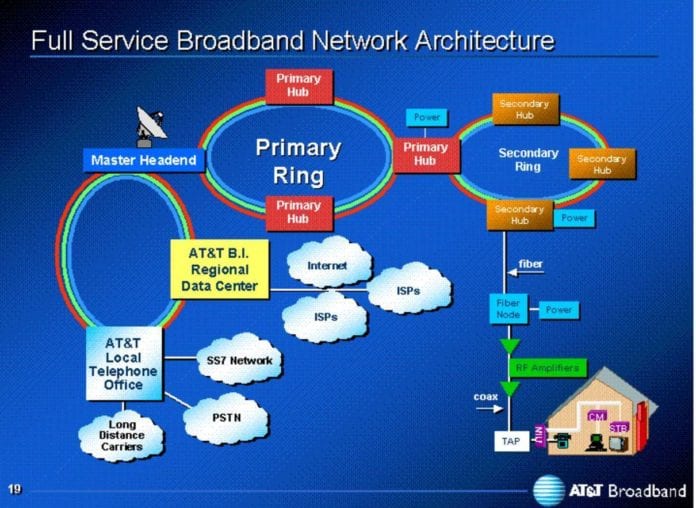

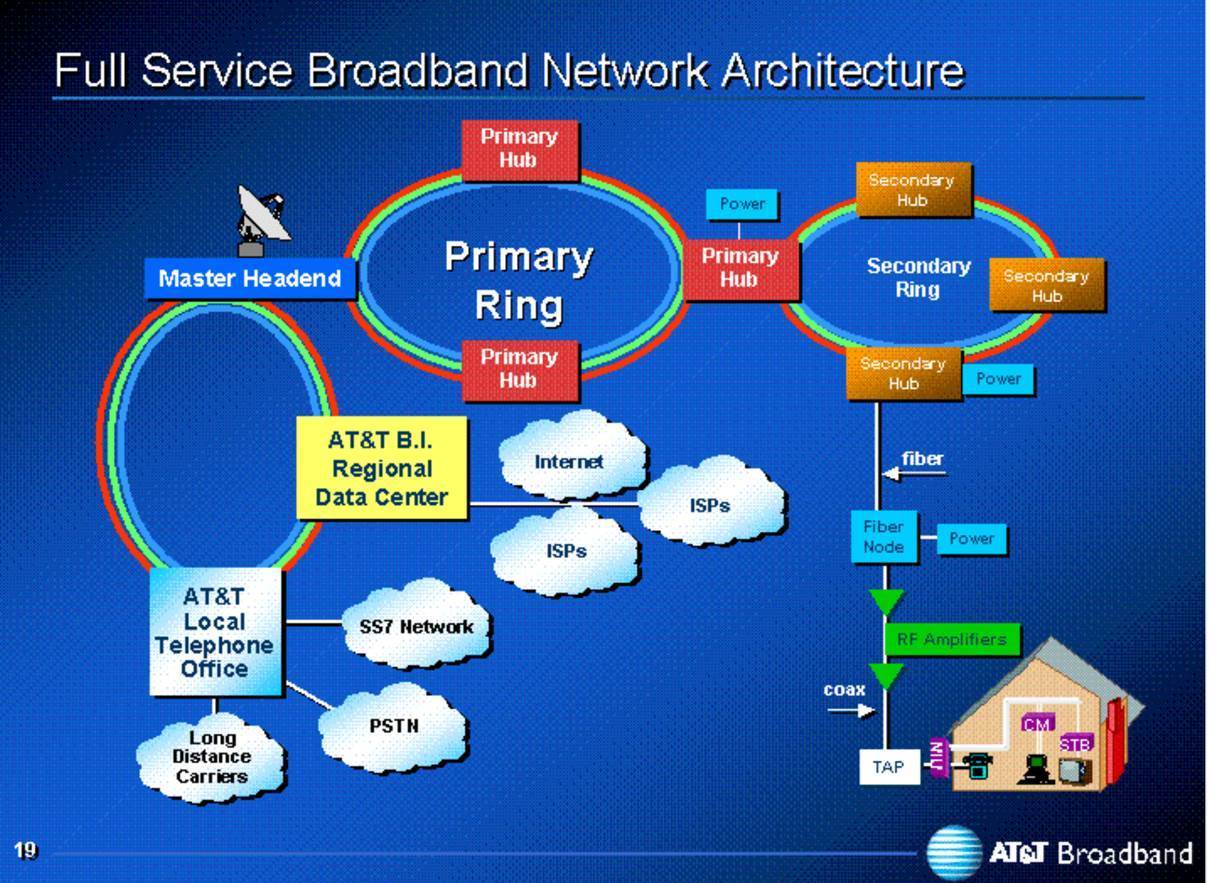

After AT&T decided to break itself up into four pieces in 2000 (Broadband, Wireless, Consumer, and Business), they had the opportunity to cover both DOCSIS and DSL technologies (see more in this detailed New York Times article here). Even then, as shown in the slide below from a 2002 SEC filing, it was contemplated that AT&T would have Digital Subscriber Line (DSL) for some types of data transmission as well as DOCSIS for broadband (not to mention Time Division Multiplexed or TDM, SONET, and eventually Ethernet technologies for enterprise customers). For a few years, AT&T provided both DOCSIS and DSL services to customers – one can only wonder what the outcome would have been had AT&T Consumer and Broadband remained as one unit.

Meanwhile, in 2004, Verizon Communications announced their Fiber Optic Service (FiOS) to battle the perceived bundle advantage of cable’s triple play. It’s important to note that this strategy change came less than 24 months after the sale of AT&T Broadband to Comcast. Many of the initial FiOS markets will celebrate their 15th birthdays next year. However, Verizon miscalculated the speed with which the cable industry would respond with their bundles as well as their upgrades of DOCSIS 2.1 (standard released in 2001 with commercial deployments starting in 2003) and DOCSIS 3.0 (standard released in 2006 with commercial deployments by 2008). The result of cable’s deployment speed was significant – local phone market share shifted to the cable industry by 20-35% over the 2004-2009 time period, quickly depleting the prospects of both DSL (specifically ADSL) and switched access cash flows.

Then, in 2016, Long Island cable provider Cablevision (now a part of Altice USA) announced plans to deploy fiber to 1 million homes (and eventually 3-4 million homes) in their territory, removing FiOS’s underlying competitive advantage for those locations. Per their most recent earnings announcement, Altice is quickly deploying the latest version of DOCSIS (3.1) and fiber to minimize Verizon’s competitive advantage and blunt any impact of 5G/CBRS as Wi-Fi replacement technologies.

A more remarkable change has occurred in the wireless industry, who collectively rallied around a single common technology standard called Long Term Evolution (LTE) by 2009. This service was eventually deployed first by Verizon in March 2011 then by AT&T starting later that year (Sprint launched LTE in 2012, and T-Mobile in 2013). Standardization (versus an alternative of up to three standards – LTE, UMTS, and Wi-Max) streamlined the device ecosystem, strengthening brands like Apple and Samsung, and resulting in the accelerated demise of brands such as Motorola (forced to Droid exclusivity and then low-end), Palm, HTC (who reached its pinnacle with the Sprint HTC Evo which was Wi-Max dependent), and Nokia (Microsoft/ Windows Mobile dependent).

Bottom line: The greater the reliance on DSL advancements (as opposed to fiber overbuilds), the faster value degradation occurred in the telco local exchanges. Slow data became the competitor-defined brand of the local exchanges, and, with diminishing share of decisions, diseconomies of scale followed. Wireless carrier adoption of a single, global technology strategy cemented the supply chain for the segment and allowed disintermediation of wireline voice services to occur at a more rapid pace (56.7% of adults are wireless-only as of the end of 2018, according to the Centers for Disease Control). Technology strategies that run cross-grain end up on the Asynchronous Transfer Mode/ HSPA/ iDEN/ ADSL graveyard.

3. Operational excellence/ marketing and product competitiveness. Once assets have been deployed and the technology strategy has been selected, the customer’s value proposition needs to be defined. While the underlying evidence of a successful technology strategy is less identifiable in one earnings call, changes in value propositions are clearly evident sooner through lower churn, higher revenues per user, and third-party recognition.

For example, Verizon announced this week that they will be the exclusive provider of the Motorola RAZR, a foldable $1,500 smartphone (more details here). Strategically, Verizon went this route to remove the prospect of AT&T exclusivity (the original RAZR exclusive 15+ years ago), not because they believed this was a transformational device (read the review in the above link for more details). Verizon’s Droid strategy (through Moto) and their Google Pixel 3 exclusivity enabled the company to have brand name devices that made Big Red’s network shine.

Another good example of a successful strategy is Time Warner Cable’s 1-hour service installation and delivery window across the Carolinas announced in 2012 (announcement here). This was accompanied by an app that reminded customers that the technician was headed to their home. They staked a claim on service against AT&T, Verizon/GTE/Frontier, CenturyLink and Windstream and forced each of them to respond.

Many case studies have been and will be written on the pricing and product strategy shifts (dubbed “Uncarrier moves”) that T-Mobile has employed over the past seven years. Three strike us as being supremely critical to their growth trajectory: a) Simple Choice plan rollout in early 2013 (announcement here); b) Binge On Implementation in 2015 (announcement here), and c) their changes in service strategy called Team of Experts introduced in 2018 (announcement here).

Earlier, we discussed the role of co-branding/ exclusivity as a part of a successful marketing strategy. Many Sunday Briefs have highlighted the puts and takes of bundling wireless with Spotify (Sprint, then AT&T) or Hulu (Sprint) or Tidal (Sprint) or Netflix (T-Mobile) or Apple Music (Verizon) or YouTube TV (Verizon) or Amazon Prime (Sprint, Metro by T-Mobile) or HBO (AT&T). A few weeks ago, we started to tackle a more fundamental question: “What’s the advantage of owning premium content (AT&T, Comcast, Altice, Canadian wireless and cable conglomerates) versus playing the field (Verizon, T-Mobile, Dish)?”

There are many more examples (good and bad) to discuss here (Verizon’s network quality marketing, AT&T’s iPhone exclusivity, AT&T’s multiple attempts to bundle wireless and wireline over the past decade, cable’s coordinated Triple Play strategy, Comcast’s Xfinity development, etc.) but the point is that no operations, marketing, or product strategy can be effective over the long, long run without the effective implementation of long-lived asset and well-conceived technology strategies. While this sounds elementary to most of you, it’s worth thinking about the abundance of ill-conceived strategies that have destroyed tens of billions of dollars of shareholder value over the past two decades. As we will discuss in part two of this strategic primer next week (called “What if?”), the blunders were both due to commission and omission.

TSB Follow Ups

I attended a private equity conference this week and walked into the cocktail reception to the question “Did you hear that John Legere might go to WeWork?” I had no response other than to describe the conjecture using my best Legere language, categorizing the report as total BS and stating that it would be more likely for John to lead a challenger technology company like Tesla than WeWork.

By the end of Thursday, T-Mobile had lost ~$4/ share over three days (~$3.5 billion in market capitalization) as investors fretted. Fortunately, by Friday evening news reports emerged that Legere was not going to leave T-Mobile for WeWork… at least yet. We are not sure whether this is a market hungry for any Adam Neumann follow-up, any out-of-Washington news headlines, or if it’s just jittery in general.

T-Mobile’s Latest Olive Branch: A Nassau County Customer Service Center

T-Mobile raised the stakes this week in their continuing public negotiation with the state Attorneys General, unveiling plans to build a new customer service center in the heart of the New York metro area (and, ironically, smack dab in the middle of the service area of one of their largest MVNOs – Altice). This is the fourth of five new service center announcements (current ones include two in New York, one in California, and one near Sprint’s current headquarters in Overland Park, KS). That leaves us speculating about the fifth location – could it be in the Lone Star State or the Windy City?

We should expect a steady stream of offerings up to the December 9 trial start. Local jobs matter even in a full employment economy, and the Nassau County announcement received a lot of local press.

Disney+ Success: 10 Million Customers Day One

After some initial reports of activation and streaming hiccups, Disney announced on November 13 that they had signed up more than 10 million customers on the first day of service. They also announced a new bundling plan (anyone watching college football yesterday couldn’t miss it) which includes Hulu Basic, ESPN+ and Disney+ for $12.99/ month (presumably to blunt the potential impact of AT&T’s HBO Max announcement). The company also indicated that they would not announce any additional subscriber figures until their next quarterly earnings call.

Will this translate into further net additions for Verizon? The unequivocal answer is yes, but how much remains to be seen. Disney+ has front page billing on the Verizon website, and they began to run ads this week touting their association with the latest streaming craze. One of the “What if?” questions in next week’s column deals with Verizon and content ownership so we’ll be discussing their “multiple choice” strategy then.

CBA Breakthrough? We Should Know Very Soon

Last Friday, the C-Band Alliance (CBA), which now consists of all of the major holders of this spectrum (3.7 – 4.2 GHz downlink; 5-9 – 6.4 GHz uplink) frequency except Eutelsat, sent a letter proposing economic terms for a CBA-Led auction. The anticipated proceeds to the US Treasury are as follows (note that these are incremental amounts to the Treasury based on overall proceeds):

Cents per MHz PoP bid % to Treasury % to C-Band Alliance

$0.01-$0.35

$0.36-$0.70

Over $0.70 70% 30%

This also comes with a pledge to conduct the auction in a timely manner (within 90 days) after FCC approval which would put it ahead of the Priority Access License for the CBRS spectrum currently scheduled for the end of June. The letter also includes a vague, good faith effort to build an open access network with a portion of the auction proceeds to improve rural coverage.

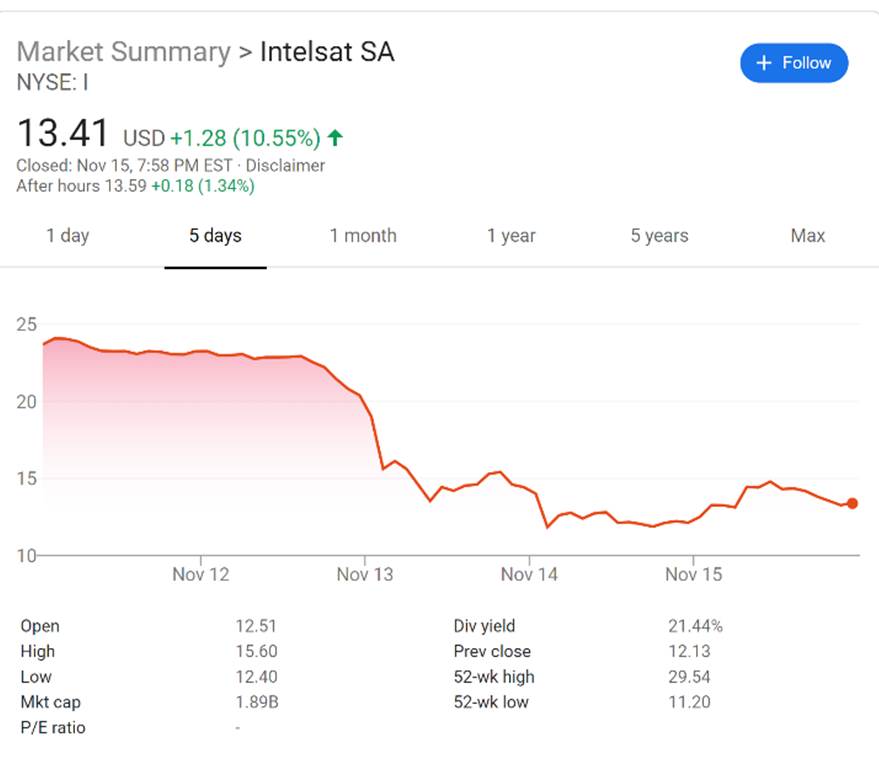

The FCC has been asked to speak with Senator Kennedy’s committee later this week, and, to make it on to the FCC December calendar, any proposal will need to be added by next Thursday (November 21). The odds of approval of any proposal by December are diminishing each day, and it’s likely that the C-Band auction will occur after the CBRS PAL auction, likely August or September. Analysts’ estimates of C-Band auction proceeds range from $10 to $60 billion. Meanwhile, CBA member stocks are trading at nearly half of their summer levels due to the uncertainty (Intelsat 5-day stock price chart nearby).

That’s it for this week. Next week, we will continue this strategy theme with several “What if?” questions (please submit yours with a quick email to sundaybrief@gmail.com) unless there is other breaking news (perhaps related to the T-Mobile/ Sprint merger or the C-Band auctions). Until then, if you have friends who would like to be on the email distribution, please have them send an email to sundaybrief@gmail.com and we will include them on the list.

Have a terrific week… and GO CHIEFS!