This article continues from here. It is an excerpt from a full report, called ‘Crossing the IT/OT divide – from co-creation to co-configuration, and how to bring industrial IoT to scale’. The report, part of Enterprise IoT Insights’ ongoing Digital Factory Solutions series, is available to download (for free) from here. Other entries in the Digital Factory Solutions series can be found here.

What does the abstract process of ‘co-creation’ look like? Well, it starts with a white board, probably. The key is all these different stakeholders are at the brain-storming, and the initiative keeps in mind the capabilities of both the technology and the business, in order to scope out a suitable change programme. It describes the task to define the ‘problem’, in fact, and not to solve it, which only comes after.

The process is hardly new, actually. Businesses hash out business plans and marketing reboots, alone and in collaboration, taking reference from all sides. But the stakes are different with IoT, because relatively little is written yet, and every business – and every production line and every plant, within each business – is different. Industrial change is not easily available off-the-shelf; it is deeply personal, highly complex, and totally unknown until the process starts.

We should consider a couple of quick examples, because the leading operatives in this sector have been working in collaboration with enterprises to design enterprise IoT solutions for some time. Software AG, in Germany, which gets routinely placed top of analysts’ leader-boards of industrial IoT platform providers, has made a formal pact of its co-creation work with a group of machine makers.

Even Magro is complimentary of it. “Theirs is the first IoT platform I’ve come across where I haven’t said, ‘boosh’. Because they do have something, there,” he remarks, ackowledging as well the Darmstadt firm’s ‘properness’ – that it has never claimed to be anything other than a software specialist.

The ADAMOS (Adaptive Manufacturing Open Solutions) collective includes German industrialists Dürr, DMG MORI, and Zeiss, and is geared towards the co-development of high-end machine and process analytics based on Software AG’s Apama-branded streaming and batch analytics, and its Cumulocity IoT platform.

It now counts 15 members; all of them are machine builders, bar Software AG. Bernd Gross, the company’s chief technology officer, says: “We are a technology enablement company. The domain specific know-how comes from partners. We have these technologies, these capabilities, and we want to make them relevant to customers through these partnerships.”

It now counts 15 members; all of them are machine builders, bar Software AG. Bernd Gross, the company’s chief technology officer, says: “We are a technology enablement company. The domain specific know-how comes from partners. We have these technologies, these capabilities, and we want to make them relevant to customers through these partnerships.”

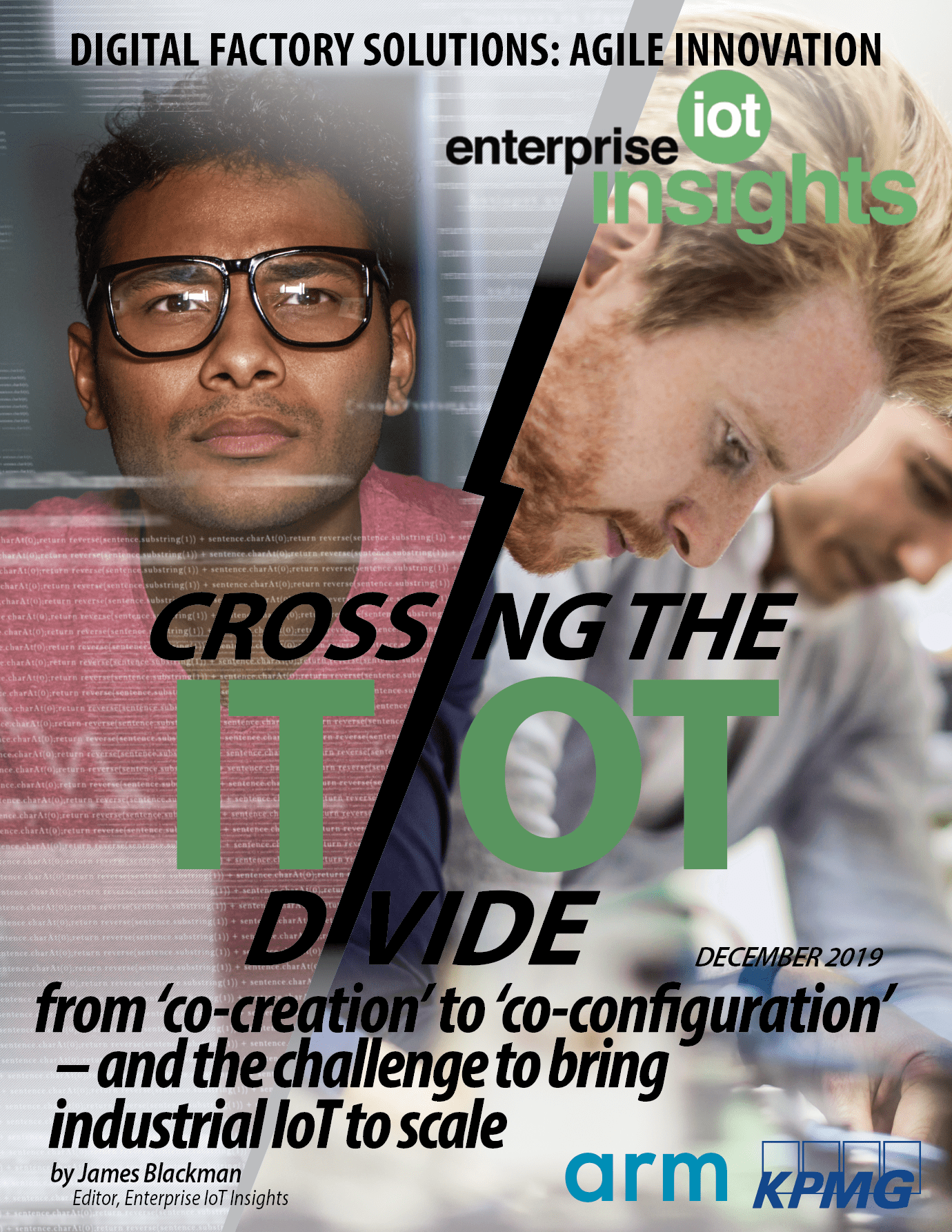

Specifically, Dürr, which makes painting robots for the automotive industry, has reworked its DXQ equipment analytics programme with Software AG to record, analyse, and eliminate faults in the painting process. The software has so far been rolled-out to around 10 car factories belonging to a tier-one automotive manufacturer in Germany.

It will be deployed in all its sites, apparently; another major car maker is in the wings, and the solution will be rolled out by the rest of its peers in time, reckons Gross. Software AG is now looking to replicate the ADAMOS model in just about every other industrial domain, for bringing value to everything from swimming pools to power tools.

Another keen proponent is Hitachi, another analyst ‘pick’ among the IoT set, which is selling digital change via its Vantara division – a business cut from the same OT cloth as Alizent, raised on the industrial knowhow and digital experimentation of its parent group, which incorporates no fewer than 80 industrial companies and 200 factories.

Innovation is not available to take-away, it observes; it has to be worked at, in partnership. “These technologies have turned a lot of heads, but the market doesn’t get it from an organisational and cultural perspective,” comments Greg Kinsey, vice president of digital manufacturing solutions at Hitachi Vantara.

“It’s a ‘people-processes-technology’ discussion, as always – where the tech is the driver. But as we mature, we will find that is backwards – that we still need to be driven by processes and talent. The technology has to fall in line.”

For the Japanese firm, it is always the same conversation: it starts as an exploratory pursuit, in close collaboration with the client, before it finds it mark, and shifts hidden levers in their systems and processes. “It is all done in co-creation,” says Kinsey.

Hitachi sets a 3:1 threshold for its digital transformation projects at the outset; Kinsey’s team will not start work, proper, until its hypothesis is projected to achieve such a return. If the ROI does not stack up, then they should down tools, and start over. If it does, they should expect to “turbo-charge” their business, even if there is an initial lag as the analytics are hammered out.

“That’s the magic number; if a client invests €1 million, they should get €3 million out the other end, in 12 months. It’s a hypothesis; but we won’t start without it,” says Kinsey.

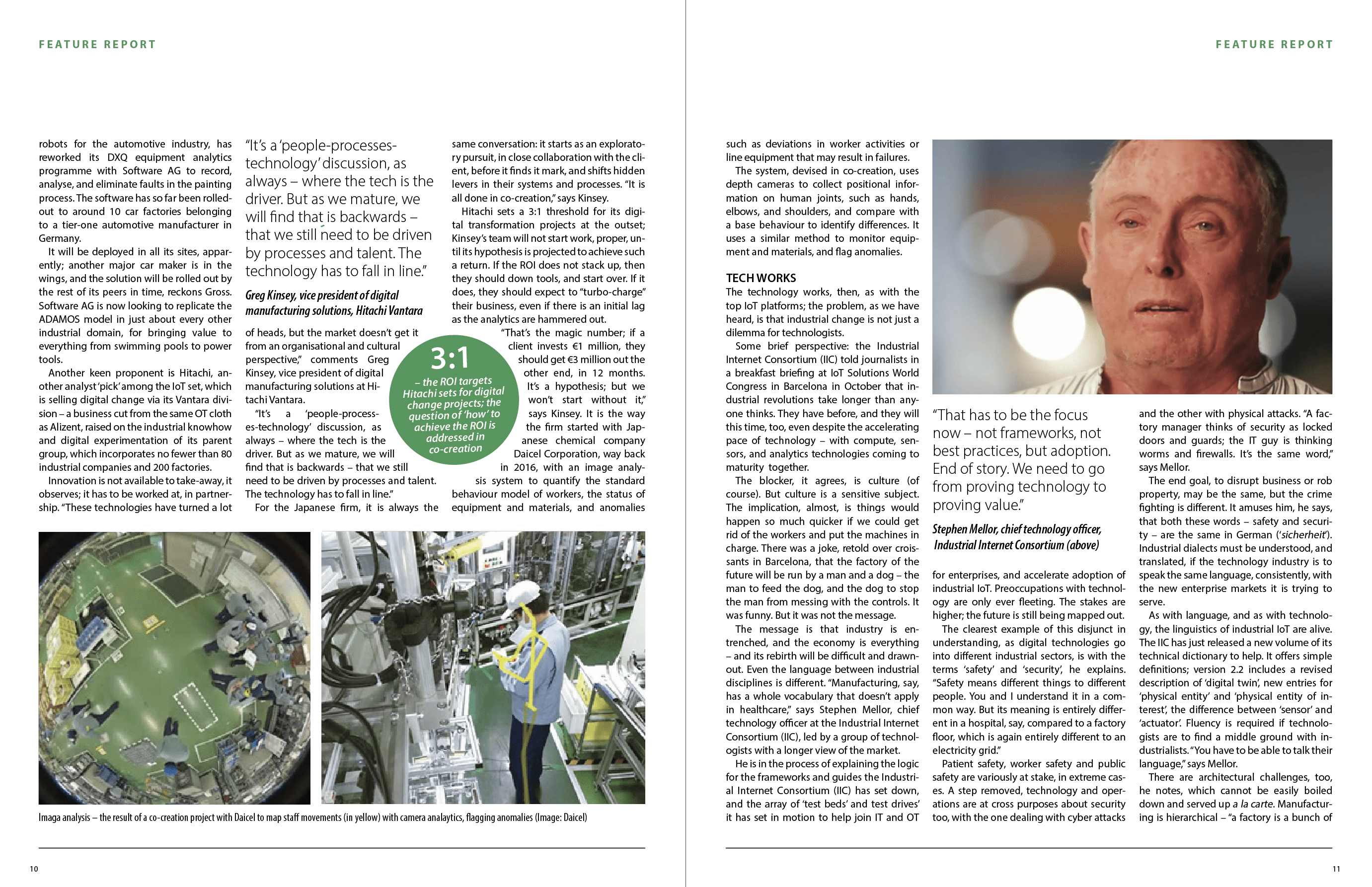

It is the way the firm started with Japanese chemical company Daicel Corporation, way back in 2016, with an image analysis system to quantify the standard behaviour model of workers, the status of equipment and materials, and anomalies such as deviations in worker activities or line equipment that may result in failures.

The system, devised in co-creation, uses depth cameras to collect positional information on human joints, such as hands, elbows, and shoulders, and compare with a base behaviour to identify differences. It uses a similar method to monitor equipment and materials, and flag anomalies.

TECH WORKS

The technology works, then, as with the top IoT platforms; the problem, as we have heard, is that industrial change is not just a dilemma for technologists.

Some brief perspective: the Industrial Internet Consortium (IIC) told journalists in a breakfast briefing at IoT Solutions World Congress in Barcelona in October that industrial revolutions take longer than anyone thinks. They have before, and they will this time, too, even despite the accelerating pace of technology – with compute, sensors, and analytics technologies coming to maturity together.

The blocker, it agrees, is culture (of course). But culture is a sensitive subject. The implication, almost, is things would happen so much quicker if we could get rid of the workers and put the machines in charge. There was a joke, retold over croissants in Barcelona, that the factory of the future will be run by a man and a dog – the man to feed the dog, and the dog to stop the man from messing with the controls. It was funny, but it was not the message.

The message is that industry is entrenched, and the economy is everything – and its rebirth will be difficult and drawn-out. Even the language between industrial disciplines is different. “Manufacturing, say, has a whole vocabulary that doesn’t apply in healthcare,” says Stephen Mellor, chief technology officer at the Industrial Internet Consortium (IIC), led by a group of technologists with a longer view of the market.

He is in the process of explaining the logic for the frameworks and guides the Industrial Internet Consortium (IIC) has set down, and the array of ‘test beds’ and test drives’ it has set in motion to help join IT and OT for enterprises, and accelerate adoption of industrial IoT. Preoccupations with technology are only ever fleeting. The stakes are higher; the future is still being mapped out.

The clearest example of this disjunct in understanding, as digital technologies go into different industrial sectors, is with the terms ‘safety’ and ‘security’, he explains. “Safety means different things to different people. You and I understand it in a common way. But its meaning is entirely different in a hospital, say, compared to a factory floor, which is again entirely different to an electricity grid.”

Patient safety, worker safety and public safety are variously at stake, in extreme cases. A step removed, technology and operations are at cross purposes about security too, with the one dealing with cyber attacks and the other with physical attacks. “A factory manager thinks of security as locked doors and guards; the IT guy is thinking worms and firewalls. It’s the same word,” says Mellor.

Patient safety, worker safety and public safety are variously at stake, in extreme cases. A step removed, technology and operations are at cross purposes about security too, with the one dealing with cyber attacks and the other with physical attacks. “A factory manager thinks of security as locked doors and guards; the IT guy is thinking worms and firewalls. It’s the same word,” says Mellor.

The end goal, to disrupt business or rob property, may be the same, but the crime fighting is different. It amuses him, he says, that both these words – safety and security – are the same in German (‘sicherheit’). Industrial dialects must be understood, and translated, if the technology industry is to speak the same language, consistently, with the new enterprise markets it is trying to serve.

As with language, and as with technology, the linguistics of industrial IoT are alive. The IIC has just released a new volume of its technical dictionary to help. It offers simple definitions; version 2.2 includes a revised description of ‘digital twin’, new entries for ‘physical entity’ and ‘physical entity of interest’, the difference between ‘sensor’ and ‘actuator’.

Fluency is required if technologists are to find a middle ground with industrialists. “You have to be able to talk their language,” says Mellor. There are architectural challenges, too, he notes, which cannot be easily boiled down and served up a la carte. Manufacturing is hierarchical – “a factory is a bunch of production lines, with a bunch of machines, each going “chk, chk, chk’.”

A self-contained industrial system can be easily transposed in trees and subtrees onto a spreadsheet, and into a data lake for an analytics engine. But structures are different elsewhere. “Try to do that with solar energy, which is completely distributed. It works in a plant; it doesn’t work outside. The same architecture won’t work over here, and vice versa.“

But how do we get to a point where industrial IoT solutions are mapped to every dark corner of industry, so they can be lifted and scaled, and the fourth industrial revolution explodes as foretold? “I wish I knew.; what happens is it bubbles up,” says Mellor.

He is being somewhat wise and somewhat disingenuous. You can’t really tell the future; you can only set the groundwork, so it comes more quickly. The IIC’s ‘test beds’ and ‘test drives’ are geared towards more practical know-how, to drive adoption. “That has to be the focus now – not frameworks, not best practices, but adoption. End of story. We need to go from proving technology to proving value.”

This article continues here. The full report, part of Enterprise IoT Insights’ ongoing Digital Factory Solutions series, is available to download for free from here. Other entries in the Digital Factory Solutions series can be found here.