Note, a version of this article appears in a new report on the asset tracking sector, called Asset Tracking – and the March Towards Massive IoT. The report can be downloaded here.

The race-to-the-bottom in the IoT market has taken another turn, and plunged downwards and outwards. Pharmaceutical and life sciences company Bayer has just announced a printable NB-IoT-based tracking label, which goes for a couple of euros, to monitor its products through the supply chain.

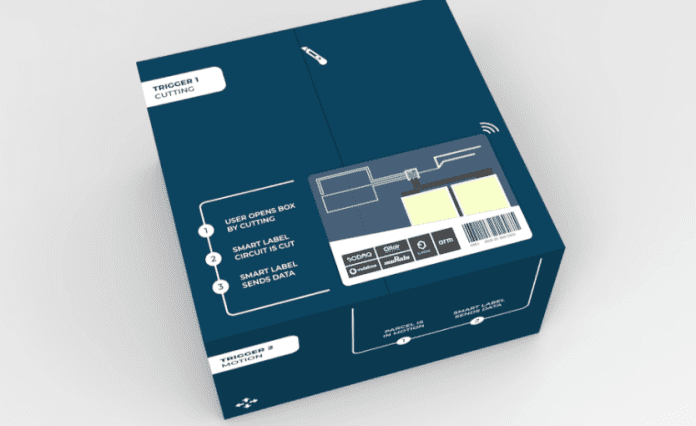

It has worked with Vodafone and Arm on the project, along with chip manufacturer Altair Semiconductor and module maker Murata. The smart label integrates cellular SIM (iSIM) functionality, as a layout on printable silicon, into the communications module, along with a printable battery, microprocessor, antenna, modem, plus a couple of sensors . Vodafone provides the reference, Arm issues the blueprint, Altair designs the chip, and Murata designs the module.

And Bayer, which has corralled the parties together, prints the tracker, like any other stick-on postage label, and slaps it on everything that goes out of its warehouses. That is the theory, anyway, and the basis for excited talk in the industry about achieving ‘massive’ IoT, finally. “The cost is a few euros, suddenly, and not a few tens or a few hundreds of euros,” comments Phill Skipper, global head of IoT business development at Vodafone.

He explains: “It breaks that glass ceiling for asset tracking. The market was constrained, before; limited to tracking of high-value goods. This changes that; it moves it down to the next layer; it resets the parameters for mobile asset tracking, and it opens up a massive new market. It brings tracking into a completely different sphere.

The solution is clever. The label connects to the cellular network when it is torn or cut, after printing and attaching to the package. Vodafone has a ‘bootstrap’ deal with Arm to provide the initial connectivity on iSIM-based NB-IoT and LTE-M devices, as well as fallback in case of outages, to enable automatic zero-touch provisioning onto local IoT networks – which, in the Bayer setup, covers Vodafone’s own NB-IoT estate, plus newly-signed roaming territories.

Skipper explains: “The question has been how to get more tracking devices out there. And two things have happened: one is the emergence of this iSIM capability, and the other is the availability of licensed low-power IoT networks – so a lower-cost implementation and a lower-cost carrier, at the same time.

“That is how we’ve reset the price point for tracking. But the trick, here, is not really the technology itself, even though that is quite clever. The trick is how to provision those devices [automatically and globally]. That is the real advance in this stick-on label; the network and all the rest of it just happen to have come at the right time.

The smart label is green(ish), as well. Is there a concern about littering the planet with little pieces of technology? “Yes,” responds Skipper. The battery, he notes, is alkaline, rather than lithium-based, and so “dissolvable”; the same for the other printed components, bar the chip, which can be easily retrieved. The group are also looking into using biodegradable plastics, made from fish scales, for the substrate, he says.

“You have the printed antenna, the printed battery, the printed input and output, and then the chip. Recovering the chip is relatively straightforward; it sort of comes off in the wash, literally. The other stuff liquefies. If you can find a clever way to deal with the substrate, then I think you are in a fairly good position.”

Vodafone has so far activated 18 NB-IoT networks, out of 26 regional operating companies. The new solution can be configured for LTE-M, or even straight cellular connectivity; NB-IoT has been pre-selected in the Bayer design to reduce the power consumption and extend the battery life, which is put at 18-24 months, depending on usage. Another clever aspect, to extend the battery and application, is the unit’s reporting schedule and functionality.

Vodafone says, after tearing and provisioning, the label reports periodically. “Once per day to tell you it’s around, and to report events after that,” says Skipper. The rota is kept to daily transmissions until the product moves out of storage, and onto the road, where cellular positioning provides a fix on the cargo. An accelerometer and temperature sensor are engaged, also, in case the goods are damaged in transit, and to trigger a response in distribution.

“Many of these companies have never had that kind of information before,” he adds.

Reporting slows, again, on arrival, in storage at the other end. Usefully, an alert is issued when the package is opened, and the seal is broken, for a second time. This indicates the product has been put to use, and provides Bayer with additional data for inventory management and production scheduling. Bayer is using the label for tracking distribution of its agricultural products, notably chemical compounds or seed packs, initially.

Robert Wollenhaupt, head of digital architecture at Bayer, says: “It means we can track every product we ship… It means we know if trucks don’t make it to their destinations… There are other use cases as well. Because a signal goes out when a bag of seed or fertiliser, or a bottle of compound is opened. It is a different view on real-time inventory, because it gives data about what’s in the market – what’s in the warehouses, and what’s in the field.

“If you know what’s been opened, then you get answers to all kinds of questions…. You know what to offer six weeks down the road, whether that is a herbicide or a fungicide, for example. If there has been a lot of rain, there’s a likelihood farmers in the area will want to treat for that. The other way around is that if you see bags of insecticide being opened in a certain region, you can deduce there is perhaps a problem with a specific pest in that area.”

The data is anonymised, at personal level anyway; the insights are zonal, and stop short of pinpointing the particular farmhouse. Wollenhaupt explains: “The data goes to outside servers. But there is enough in it to be able to draw conclusions, without knowing which seed packs and which growers are involved.”

He says cellular positioning, using tower triangulation plus “some magic” data analytics, is good enough, and crucial to keep the cost down. “The problem with GPS is it would add too much cost and use too much power. The label needs to have sufficient battery power to cover storage, distribution, delivery to the growers, and some storage at that end, as well. We are shooting for two years’ battery life, with one data transmission per day – ballpark.”

Vodafone has devised a settlement model to expedite international roaming for the Bayer solution, and to set a template for future roaming of mass-market smart-label products. The rationale is that existing roaming compensation, as it exists in the consumer market, cannot be easily reworked for massive volumes of IoT devices carrying scanty data loads; the calculation has to be simplified, especially as the cellular IoT market finds its feet.

Skipper says: “Roaming, really, is just about talking to enough operators. But with NB-IoT, there is a different model – because these devices don’t consume lots of data. The agreements we have are based on settlement; we say, look, there are 100 or 1,000 devices on the network, so let’s call it 100 or 1,000 times X, rather than calculating how much data is actually going over the network. Which makes it very simple to get started with these agreements.”

Deals with AT&T and Deutsche Telekom have been done, he says; “loads of others” are in process.

Bayer retains the intellectual property (IP) rights to the smart label solution. It wants to industrialise its group innovation in order to drive the price down. The firm translates “a few euros”, as Vodafone positions the tracker price, as €5, in fact; which is some way off the dollar mark France-based outfit Sigfox claims it is approaching, with a rival non-cellular version of narrowband IoT networking.

But the market wants a cellular equivalent, reckons the team behind the Bayer tracker, offering global connectivity, remote provisioning, and more functional two-way communications. “We know others are interested – to be able to connect tracking devices automatically, anywhere on the planet,” says Wollenhaupt.

He goes on: “The idea is to share this innovation more widely across the industry, and not only to keep for ourselves. For us, just for the crop sciences division, we are talking about hundreds of millions of packages and bottles, and so the potential volume is significant. But if you think about the wider market, and how much gets shipped across the board, then there is massive volume, potentially.

“We are not at that point, yet. But we have products of all different sizes – from thousand-litre containers down to three-litre bottles. We can track the bigger containers, anyway, because the compound is expensive, and we want to know if it doesn’t arrive. And if we drive the price down far enough, it starts to make sense for the smaller items, as well – maybe not for every bottle, but at least for some of the bottles on the pallet.”

Skipper remarks: “This market has been limited to shipping containers and heavy equipment, and spare parts for aircraft, and pallets of perfume and whisky; all of these very high value goods. All of a sudden, with this, you can track very simple products, like a box of agricultural fertiliser – and down even to something like a bottle of cognac. It is the starting point of something much, much bigger.

“I can’t tell you the exact arrangement with Bayer, but there is certainly interest from other industries – from people that use bottled gases and fuels, and all those sorts of things. That will be the next piece. And it brings a number of advantages. One is that we have a first-mover advantage; the other is it reinvigorates the whole low-power debate – because talking about a few hundred thousand devices is very different to talking about a few million.”

Does it put the cat among the pigeons for the non-cellular guys, which have so far had a run on this market, while the cellular community has busied itself with network building, device availability, pricing models, and global roaming? ABI Research reckons four in five asset tracking devices are being made for cellular low-power wide-area (LPWA) networks, and that the balance will tilt away from their proprietary equivalents some time after 2023.

The question should, almost, be whether this single innovation marks the start of the end for the likes of Sigfox and LoRaWAN; except, of course, logic says each technology will retain its particular niche (so long as it remains in business). The follow-up, then, is: will these niches narrow further with the advent of this new smart label product? “Yes. I think it puts everything on a par,” responds Skipper.

He goes on: “The thing is we get all the scale advantages of running consumer, enterprise, and IoT [traffic] in the same family, in licensed bands. It is difficult, by comparison, to build, secure, and maintain a network just for low-cost IoT devices. Because we can draw on these wider resources, we can punch above our weight in IoT — like everyone running in licensed bands.

“Companies want low-maintenance, high-security solutions, and, as this moves on, it becomes less about the cost of the product and more about the cost to serve these devices in the market.”

Note, a version of this article appears in a new report on the asset tracking sector, called Asset Tracking – and the March Towards Massive IoT. The report can be downloaded here.