A SpaceX flight scheduled for Friday will carry dozens of small satellites into space, a “rideshare” launch with low-earth-orbit-bound equipment that will include one particular microsatellite that aims to map the global rollout of 5G networks, with a view from space.

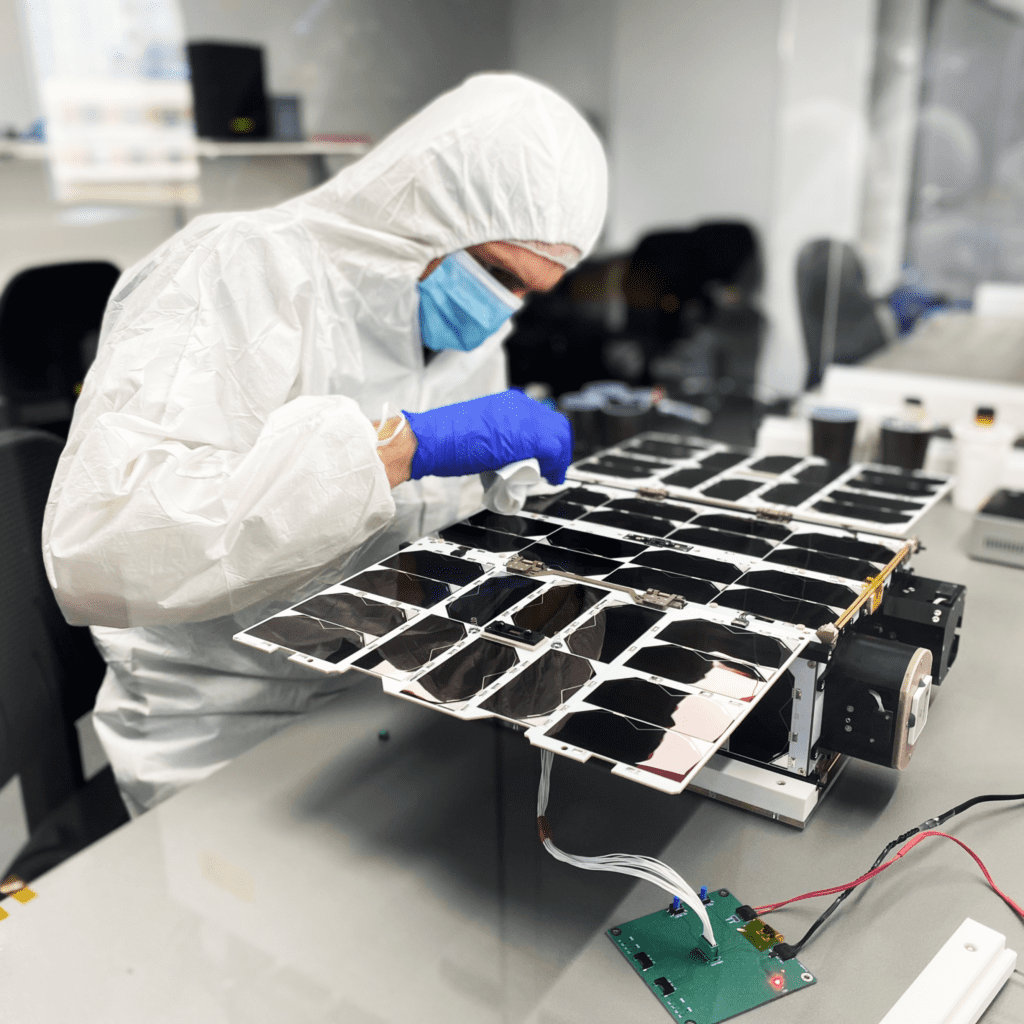

The cube satellite nicknamed Charlie, about the size of a carry-on suitcase, bears a specialized radio frequency sensor that is about five inches square, with three antennas that can detect radio frequency activity up to 40 GHz. It is the first of two to be launched by Aurora Insights and microsatellite platform company NanoAvionics that will orbit the globe at a height of about 500-600 miles, scanning RF spectrum on Earth and detecting where different network technologies, including 5G, have been deployed, according to Aurora Insights CEO Jennifer Alvarez and F. Brent Abbott, CEO at NanoAvionics US.

Aurora Insights provides carriers, cable companies, telecom equipment companies and regulators around the world with information about the spectrum environment, for clearing and interference-hunting purposes as well as competitive information about the extent to which networks are actively operating in different geographies. Typically, its sensors are mounted on land-based vehicles or fixed locations, or even on aircraft — but now, it is adding space-based data to its view of the planet’s wireless networks.

“The reason that space is so important to us, is that it gives us the high ground — we are immediately global in our coverage” and can frequently revisit geographies, because the satellite will orbit the planet about every 90 minutes, Alvarez said. “It gives a more macro or synoptic view of the planet, and the wireless activity of the planet, that can be used to map what’s going on in the RF spectrum all over the globe—but also to direct our terrestrial resources, our ground-based resources and air, to do more in-depth investigation—so we can map the roll-out of 5G base stations, for example.” The Charlie sensor records the entire breadth of spectrum up to 40 GHz, Alvarez explained, and then the data from all of Aurora Insights sensors — terrestrial, airborne and space — are combined and undergo “heavy-lifting processing” as Alvarez calls it, that allows the company to glean detailed information: Is a specific band being used in a specific location? Where are the base stations? What technology (3G? 4G? 5G?) is being used?

“You can develop an entire network topology,” she said.

Charlie is one of two satellite-born sensors — the other is Bravo, which will join Charlie in orbit soon — that will augment the company’s global RF view. Aurora had an Alpha mission as well, which was an experimental satellite about half the size of the Bravo and Charlie missions—and it’s still operational.

Alpha, she says, “was really a pathfinder for us, in that there were a lot of naysayers that said with a low-cost satellite, with low-cost electronics and not an exquisite antenna, you’re never going to be able to see terrestrial signals, because … terrestrial signals are generated on the ground, and they’re meant to stay on the ground.

“But in fact, with Alpha, we were able to prove that we can see substantial amounts of signal energy [from] space, and that informed our Bravo and Charlie developments,” Alavarex continued. “Now we have a much higher capability going up.” Charlie, she adds, is the company’s most advanced sensor yet, with expanded range and sensitivity. Aurora Insights signed its contract with NanoAvionics in January 2020 and despite the global disruption caused by the coronavirus pandemic, the two companies were able to get Charlie set for launch within 12 months. The cube sat is expected to circle the planet for at least three years, with a goal of up to five years.

“With that tiny satellite, we are going to be getting massive amounts of data every single day, globally,” Alvarez said.

What questions is Alvarez eager for Charlie’s data to help answer? She has a long list, but the first topic on it is the same one dominating telecom: 5G, specifically, midband 5G deployments between 3-4 GHz around the globe. Aurora Insights has been mapping the midband over the past year, she says, and hasn’t seen a particularly high level of activity. “As we see 5G roll out, we expect the world to light up with 5G signals in that midband region,” she said.

She is also interested to get a global view of how the millimeter-wave 5G roll-out is going — and yes, Charlie will be able to detect mmWave, if not quite with the same granularity as some other airwaves, but enough to give Aurora’s terrestrial and air-based sensors somewhere to start. mmWave 5G, Alvarez notes, doesn’t propagate far or penetrate obstacles well – but it does scatter. “What we have learned from our aircraft experimentation and data-gathering with mmWave is that you can actually see, from the altitude of an aircraft, that there’s mmWave 5G in a city – and in fact, using our technology, we can narrow it down to neighborhoods of activity,” she said. “So from space, we expect to be able to see the 5G mmWave signals.

“Picking out individual towers or transmitters is probably a challenge that’s too far for our Charlie mission, but sensing that there is mmWave 5G activity in a region is what we’re hoping for,” Alvarez said.