After all the false starts and funny looks, is it time to take MulteFire seriously? Nokia says so. And, as the mainstream telecoms market wakes up to the Finnish firm’s long-time message about the industry-changing potential of private cellular, it is probably worth listening. Because Nokia has the first-ever MulteFire device in the bag, at last, and a first-mover advantage on 14-odd million customers in its sights, it reckons.

We should watch for hyperbole, here, which attaches to the industrial LTE/5G market like a rash. But Nokia must get credit for sticking to its guns on MulteFire, as a technology to explode private LTE into unlicensed 5 GHz spectrum, as mobile operators hated the idea from the start, 3GPP circles forced its proponents into the shadows, and even its compadres in the old MulteFire Alliance laid down their arms. That is the sense, at least.

The hope from Nokia is that, after countless setbacks, including at least a couple of global lockdowns, the late arrival of a certified MulteFire router will spur the rest of the market, including Qualcomm and Huawei as its stop-start partners in the alliance, as well as old familiars like Ericsson, conspicuous by its total absence from the story, and the operator set, which has only just accepted Industry 4.0 means different digital strokes for different enterprise folks.

Because, Nokia says, enterprises need multi-layer private LTE/5G networks, with additional airtime capacity across additional spectrum bands, to serve their multi-layered ambitions for digital change. And because, it argues, Wi-Fi, even as Wi-Fi 6, won’t cut it. In the end, the problem with cellular is still spectrum, even after US and German regulators have shown the world how to carve-out airtime for privately-licensed local-area networks.

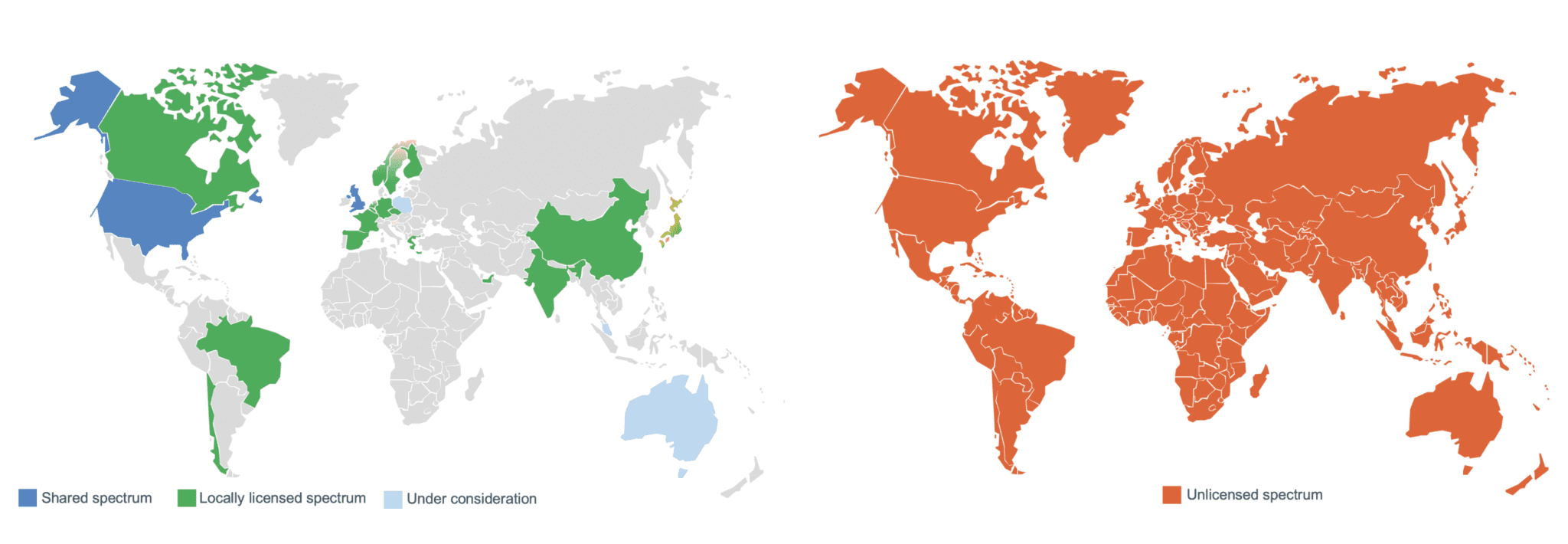

Similar licensing mechanisms are in place in “perhaps 50” countries, it reasons; but “another 130” have no recourse for enterprises to get started with private LTE/5G, except for discretionary local handouts from national operators. Plus, the fact is that, however cheap and easy ‘vertical’ spectrum is to obtain, it remains an administrative faff, which most enterprises – most of the 14 million Nokia counted-out two years ago – would prefer to live without.

Stephane Daeuble, head of marketing for enterprise solutions at Nokia, explains: “If you are in this private wireless market, then this is the bigger picture. We are talking here about boosting the market significantly. Because suddenly it is not just about the 20 largest enterprises in each sector, but about all the rest of them – the other 80 percent, or whatever. All of the SMEs in the world. Because these 14 million sites are mostly smaller companies.”

He continues: “MulteFire will be the way to scale private wireless – from the 290-plus customers we have today to thousands of networks. And a big reason it will accelerate momentum for private wireless is that unlicensed 5 GHz spectrum is plentiful and global, and costs nothing… We are pretty excited, because Nokia is uniquely positioned. Nokia will have an unfair advantage for six or nine months, because we are the only one with a MulteFire solution.

“We expect to increase our share in private wireless, and to accelerate the market in general. Over time, we want to get to a point where others – Ericsson included, and operators, and chipset vendors, and everyone in the private wireless market – look at it and say, maybe we are missing something, maybe we should do something [so the ecosystem] drives the chipset vendors [to produce MulteFire solutions].”

Troubled times

This last part is telling, of course. The market had largely given up on MulteFire. After releasing a compatible base station three years ago, and scouring the market for partners to produce devices ever since, Nokia has gone it alone to develop both the chipset and user equipment. Its new MulteFire 700 router – available next month (August), with MulteFire live as well in Nokia’s popular digital automation cloud (DAC) private network solution – is only one device, but there is pent-up demand, it reckons. So where was Qualcomm, exactly? Where was Huawei?

Nokia will not point fingers, or say much at all. But the chicken-and-egg of supply-and-demand has hatched/birthed a late-starter with MulteFire, as the former had its head turned by the consumer rush on 5G, and the latter has been living through a garish geopolitical nightmare (which hasn’t squared with a US-registered alliance). Parallel news about the alliance’s rebranding and repositioning is to ensure the same mistakes are not repeated with 5G.

Daeuble comments: “We held up our end of the bargain. We created the small cell, and scanned the market to complete the solution. But no one put their money where their mouth was. So we did it ourselves. We produced the device, we completed the vision – for private LTE to be mass market, and available to SMEs. As first to market, with significant demand, we hope others will see the momentum, and build chipsets so the ecosystem grows.”

Some backstory, quickly. The deal, back in 2015, was Nokia and Qualcomm would develop MulteFire together, having settled on a “vision” to “tap any spectrum that could be found” for private LTE. They had been voted down in 3GPP, with operators pushing a hybrid agenda to use unlicensed spectrum like a data pump to boost the downlink channel on public LTE networks, while retaining the uplink and control channels in regular LTE spectrum.

“3GPP was driven by operators at the time, and they wanted LAA and LWA. Everyone voted, and no one voted for full LTE in unlicensed. So 3GPP did all this work, including introducing DFS and LBT to enable LTE to coexist with Wi-Fi,” says Daeuble. The same frequency selection (DFS) and listen-before-talk (LBT) mechanisms from license assisted access (LAA) and wireless LAN aggregation (LWA) were carried into the MulteFire project.

“We thought they were missing a trick. We had this vision, and we wanted to stay on top of 3GPP. So we created the alliance with Qualcomm, to do the next five or 10 percent of work to bring LTE fully into unlicensed – to make it possible to use LTE in this 5GHz band anywhere in the world. That was the remit. And all the time, 3GPP said it made a mistake, and needed to bring [the work] back inside. Which is what has happened with 5G NR-U.”

Proving ground

The separate announcement this week from the MulteFire Alliance, rebranded as MFA, reflects this, with the MulteFire donkeywork going back into 3GPP with development of standalone 5G NR in unlicensed (5G NR-U) spectrum. The alliance has moved away from technical development, then, to focus on industrialising 5G – in all licensed, shared, and unlicensed spectrum, under the ‘Uni5G’ brand – for enterprises, and the telco industry at large.

The emergence of 5G NR-U restricts MulteFire as an LTE technology, effectively, without a brand to speak of in the next 5G world. But for now, the LTE version of 5G NR-U has years of life – probably decades, for some use cases – left in it, says Nokia, and will live long anyway as the foundation for cellular in unlicensed spectrum. But the success of both the new Nokia router and new MFA ecosystem-building will show the way for 5G NR-U, as well.

“This is the proving ground for private wireless in unlicensed spectrum. Because if we are not careful, 5G NR-U will be like MulteFire – where we have the standard, but have to wait five or six years to get going with it.” But is there room, really, to be so optimistic after all this time? Nokia sounds sure of it – as it has sounded with so much of private wireless for the last few years. Let’s look at its rationale, this time out.

Nokia has outlined three use case scenarios, plus a bunch of new sales channels. The first is as a complement to licensed spectrum, whether for national or local infrastructure, as a means to run multi-layer private setups. Nokia’s customers already want additional capacity, it says. Daeuble suggests a scenario where a construction company chooses to run critical crane operations in licensed LTE channels and non-critical camera sensors in MulteFire.

Even with progressive regulatory regimes, such as in the UK and France, local LTE licences are limited to 4.5MHz and 5MHz channels, he notes – and relatively expensive, too, in the case of France. The second “opportunity” is with temporary installations. The same firm might stick to MulteFire for all its site comms, and move it around as itinerant infrastructure, says Dauble. “Sporting events, construction, broadcasting – these want flexibility, not fixed licences.”

He uses the example of a surf competition, stopping in “California, Australia, Portugal”, following the summer with a MulteFire backpack. A press statement names US-based Safari Solutions, which provides fold-up/down IT systems for sports events and trade shows, as the first customer for the new Nokia kit, which gets its official release in August. “A huge improvement on Wi-Fi… and [a] reduced dependency on commercial networks,” the firm states.

New markets

The third is with “new customers and markets”, which really include the temporary and expanded LTE scenarios listed above, but also all the SMEs in Nokia’s 14 million industrial targets. “For them, MulteFire is a good fit – no registration, no extra cost, just easy-going deployments,” remarks Daeuble. Crucially, higher-volume expansion of private LTE into the SME sector brings the operator community, initially reluctant, into the fold on the supply side.

He explains: “The whole story has changed. Even if the operators weren’t very keen on MulteFire initially, they have started to realise they need to create segmented offerings for different parts of the market. And we know operators will play a big role with SMEs, and MulteFire is another way to tap into the SME market – without messing with public network spectrum. Which means no radio planning, no interference, no optimisation of layers.”

Because MulteFire works in unlicensed spectrum, it also affords mobile operators a way to go beyond the bounds of their old spectrum licences, and offer private LTE to enterprises anywhere in the world. It is the same for Nokia itself, which has been painted like the bad guy for bypassing its traditional carrier channels to sell directly to enterprises and crack the market open.

Because MulteFire works in unlicensed spectrum, it also affords mobile operators a way to go beyond the bounds of their old spectrum licences, and offer private LTE to enterprises anywhere in the world. It is the same for Nokia itself, which has been painted like the bad guy for bypassing its traditional carrier channels to sell directly to enterprises and crack the market open.

“If you look at a map of our private wireless customers today, most can be linked to licensed vertical spectrum in their country, or else to leasing agreements we have with local operators there. The point is there is no spectrum in lots of countries, and no means to get it – look at Asia, the Middle East and Africa. Because otherwise, we would have customers in those regions. We hope MulteFire gets us into those markets.”

Daeuble adds: “We hope that it gets private wireless into the SME market, and opens opportunities for operators, and for other distribution channels.” How soon will Nokia announce a go-to-market deal with a mobile operator, offering MulteFire a standard part of their enterprise portfolio? “The countdown clock starts now – as soon as the product goes on sale next month,” he responds.

Reseller channels

More intriguingly, perhaps, plug-and-play MulteFire solutions might breathe new life into beleaguered independent dealer and distribution channels. The industry’s move to off-the-shelf hardware and open-source software is accelerating, of course, and the trend to simplify its management for localised non-specialist operators is also deepening. But MulteFire goes further, and makes LTE almost Wi-Fi-like, finally, reckons Nokia.

“These high-volume channels are an excellent fit, as well – these disties and VARs selling Wi-Fi access points from Cisco and Aruba, and all the rest. In the past, private wireless was too involved for them. It was like, ‘Oh my god, so I have to think about spectrum, and registering and blah-de-blah? But now with MulteFire, they can have a private LTE offering that is very easy for high volume [sales].”

“DAC is our solution to make private wireless simple. And MulteFire makes it even simpler – it epitomizes the whole concept of plug-and-play ease-of-use. Because you have it as-a-service, shipped in a box. Which is the whole concept. And operators, which want to serve the SME market, are used to selling femto solutions to shops and venues, and want easy sales they can shift like Wi-Fi. And with MulteFire, they have that for private wireless too.”

The other factor is performance. MulteFire is better than Wi-Fi, says Nokia. It is better in terms of coverage, penetration, and performance, even compared with Wi-Fi 6. In testing, Nokia claims a coverage range of 720 metres, compared with about 200 metres for Wi-Fi 6. “You have three-and-half times the coverage radius, and about ten times the total coverage from a single cell. Which means lower costs, potentially, just because you need fewer cells.”

Equally, payload fluctuation is dramatically reduced, from “massive” variation to relative stability, and handover is negated, compared with multi-second dropouts on Wi-Fi.

Daeuble says: “Clearly, Wi-Fi 6 has brought some new capabilities, but there are still lots it does not address. Whereas MulteFire, through its combination of spectrum easiness and LTE goodness, meets those requirements. In the same spectrum, with the same output power, it offers a significant improvement in terms of coverage and penetration, which means a significant improvement in performance.

“Clearly, latency is higher than with a normal LTE network – in the 40-50ms range, rather than the 10-20ms range. But it is still more reliable than even WI-Fi 6 today – which goes up to 100ms as soon as you put 20-25 things onto the network. The same with throughput; the more devices connected on Wi-Fi, the lower the total throughput. Whereas it stays roughly the same with MulteFire. Plus, you get military grade security, and mobility as well.”

It’s a good story, anyway, as it usually is from Nokia’s private networks team. Time will tell.