This is article is taken from a recent editorial report on Industrial 5G Innovation – From Setting Standard to Becoming Standard; the previous instalment in this serialised version of the report is available here. Subsequent instalments are listed below (linking either to the original report, or to web articles, as they are available). The report includes additional features and interviews, and is available here. A webinar on the same topic is also available, here, with speakers from ABI Research, MFA, Schneider Electric, and Vodafone.

But have we got this wrong? Is this delay less with the standard makers and more with the system makers? Or is it just the natural chicken-and-egg cycle of cellular? Like Vodafone says (pages 22-24), we have been here before, notably with NB-IoT – which is only now, after being introduced in Release 13 in 2016, starting to look like the real deal. And besides, there are other challenges before 5G comes of age; none bigger, perhaps, than spectrum.

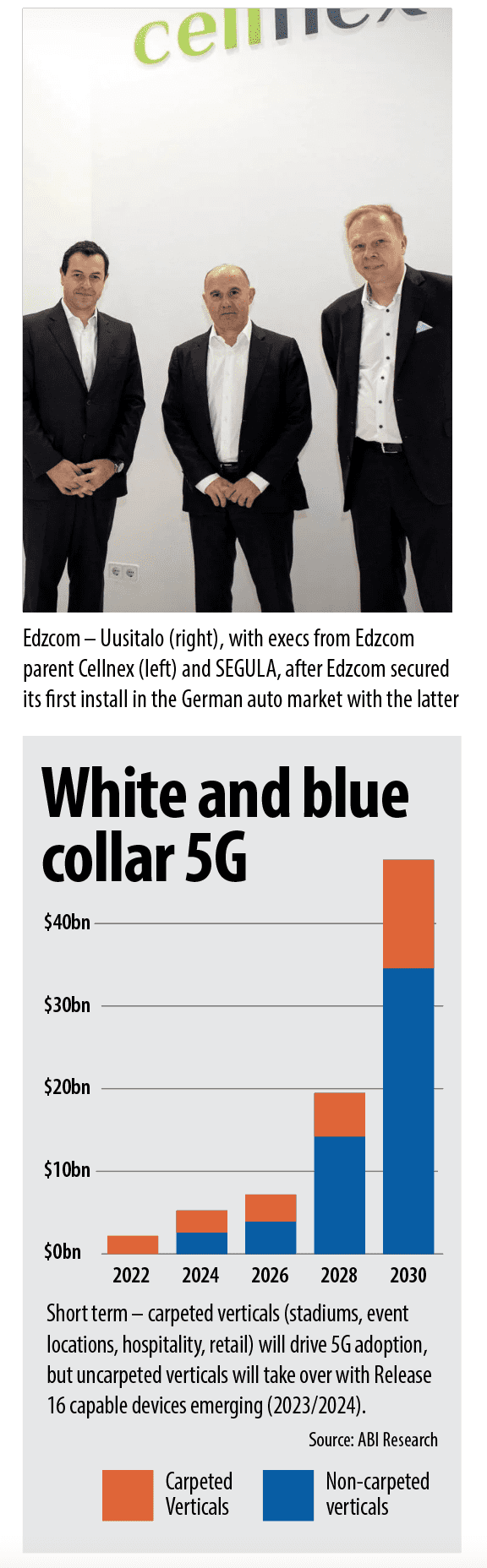

Ask a private 5G specialist about the order of play in cellular Industry 4.0 setups, and it will tell you spectrum is the first consideration, always, and not networks or devices. “Everything starts with spectrum; that is still the key component,” comments Mikko Uusitalo, chief executive at Edzcom, the Finland based and Spain (Cellnex) owned industrial networking outfit that has made a lot of the early running in the private 5G space.

He explains: “The market is quite fragmented in Europe, still, compared to the US, which has enabled it with CBRS for everybody. The EU should have done the same for enterprises. Instead you have to go nationally, because spectrum is regulated nationally, and pick the radio vendor accordingly. That is the first decision. Because not all the vendors – not even Nokia – support all the bands. The core network, meanwhile, is more of a commodity.”

He explains: “The market is quite fragmented in Europe, still, compared to the US, which has enabled it with CBRS for everybody. The EU should have done the same for enterprises. Instead you have to go nationally, because spectrum is regulated nationally, and pick the radio vendor accordingly. That is the first decision. Because not all the vendors – not even Nokia – support all the bands. The core network, meanwhile, is more of a commodity.”

He repeats the mantra about the build process; to start with spectrum, before picking vendor partners. “The drivers are spectrum, radio, core – in that order. And then, how you design and how you operate [the infrastructure]… And all of it is driven by the use case and the cost – the demand for geo-redundancy, say, and the budget availability.” This is important, about regulatory fragmentation, to understand how the private 5G story has skewed between regions.

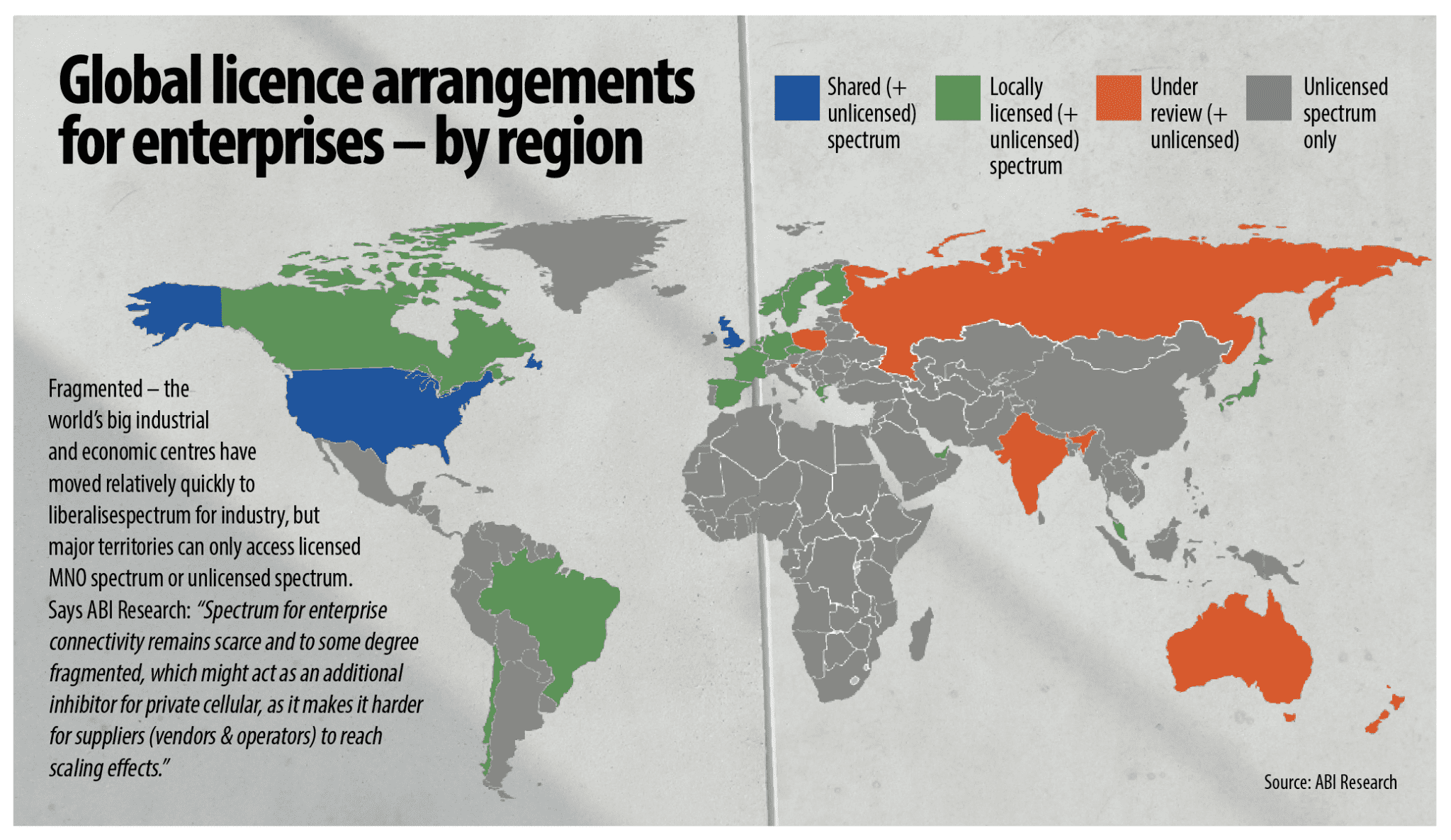

Back to Leo Gergs again at ABI Research, with data about licence applications. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has granted 20,625 private access licences (PALs) in the 3.55-3.7 GHz CBRS band in the US, he says – a number that does not, apparently, include general authorised access (GAA) requests. BNetzA in Germany, which has set the tone in Europe for all-in industrial 5G, has issued just 220 licences in the 3.7-3.8 GHz band.

He has a guide figure for China, too: 3,000 private network deployments by 2023, as set out in the Chinese Ministry of Industry and Information Technology’s so-called Set Sail action plan in April 2021, which defines qualitative and quantitative targets for the country’s whole 5G market. The China situation is hard to know, of course; but the US run-rate and the China target, at least, make Berg Insight’s figure of 13,500 installations by 2026 look conservative.

Plus, its count-up from a few months ago (March), of 1,300-odd existing private LTE/5G deployments (as above), looks a little short – considering the FCC figure of 20,625 PAL licences, and Nokia’s 400-500 customers, multiplying fast (pages 26-28), plus the likes of Airspan, Athonet, Cradlepoint, Druid Software, Edzcom, Metaswitch and many others putting in useful numbers, separately and together; plus all the EU testbeds, referenced by Gergs previously.

Of course, licences do not mean networks, always; but Federated Wireless, which has so far handled about 42 percent of CBRS applications via its spectrum access system (SAS) mechanic, claims 350 customers and 90,000 radio units (“cell sites or access points”) – and “1,000 new nodes per week”, the story goes. And then there is UK-based Quortus, newly acquired by Ericsson, which has talked in these pages of its “first 2,000 networks”.

Clearly, someone cannot add up (or will not contemplate unverified numbers), or someone is lying (or gaslighting the market) – or else someone is just not doing their journalistic duty. But it is an investigation too-far for this report, and does not matter much anyway. The point is private cellular is going at a good clip, even if there are relatively few proper 5G devices for industry. Which suggests the spectrum landscape is getting easier, at least.

At the same time, it is not easy enough. Uusitalo’s complaint is about European spectrum fragmentation, and Gergs’ licence numbers say Germany, the self-appointed European HQ for Industry 4.0, is struggling to make private 5G scale anyway, beyond parochial trials with the big beasts of industry – even with a 100MHz licence available for the price of a high-end smartphone contract (€550 per year on a 10-year deal, Siemens says).

On the first point, fragmentation is as much about licensing systems in each locale, as frequency range. Europe has generally settled on different tranches of the mid-range N77 and (largely) N78 bands at 3200-4200 MHz, with some lower (and very high) range provisions on top. The European Commission has directed CEPT, the bloc’s coordinating body for telecoms, to study harmonisation upwards of 3800 MHz (the top half on N78) for local 5G applications.

But in the meantime, it is a sketchy picture of mid-range grab-bags, says an April 2022 whitepaper from Ericsson. Germany’s 100MHz provision, for instance, allocated in 2019, is at 3700-3800 GHz (Band 43). By contrast, France is offering 4x50MHz at 3490-3800 (B42/43), but only via mandated local sub-letting of national spectrum by mobile operators; French regulator Arcep has set aside 2575-2615 MHz (B38) as privately licensed spectrum for enterprise usage, available in 40MHz chunks.

Sweden is licensing 3760-3800 MHz for enterprises, also in 40MHz pieces; Finland is offering 20MHz at 2300-2320 MHz for the same. Most other countries are going via operators, as with the B42/43 provision in France. The Czech Republic is offering split 20MHz options via carriers at 3400-3480 MHz and 3640-3700 MHz; Denmark has a leasing option at 3740-3800; Finland and Norway have obliged operators to ‘play nice’ with enterprises at 3400-3800 MHz.

By turn, the UK model for enterprise spectrum looks like the most progressive; a compromise with, and an advance on, the CBRS option in the US, perhaps, with Ofcom pre-empting the (post-Brexit) EU drive on 3800-4200 MHz by granting local shared-access in the 1800 MHz (1876.7-1880 MHz) and 2300 MHz (2390-2400 MHz) bands, sections of which are in the hands of public network operators, and liberalising everything at 3800-4200 MHz for enterprises.

By turn, the UK model for enterprise spectrum looks like the most progressive; a compromise with, and an advance on, the CBRS option in the US, perhaps, with Ofcom pre-empting the (post-Brexit) EU drive on 3800-4200 MHz by granting local shared-access in the 1800 MHz (1876.7-1880 MHz) and 2300 MHz (2390-2400 MHz) bands, sections of which are in the hands of public network operators, and liberalising everything at 3800-4200 MHz for enterprises.

The point, again, is European enterprises are not in position to avail themselves of an easy SAS mechanism, such as in the US, to bag local spectrum across the continent. They have to go, via vendor and integrator partners, market-by-market, and regulator-by-regulator, and sometimes operator-by-operator. It is a mess, we hear, and it is making industrial 5G into a slow-burn.

Which is why the old MulteFire story, to appropriate 3GPP tech for unlicensed spectrum, has regained momentum. Nokia says MulteFire – under the guidance of MFA, the rebranded MulteFire Alliance – is finding traction with industry, at last, after a drawn-out incubation that saw fellow MFA founders Qualcomm and Ericsson go AWOL and a lack of hardware (shock) make it a joke, almost, but for Nokia’s blue-eyed pursuit of more Industry 4.0 spectrum.

Stephane Daeuble tells how Nokia has just – via an operator – won a major supply deal with a “very large food and beverage company” on the back of its MulteFire offer. Nestlé? PepsiCo? AB InBev? Who? Daeuble is not saying, but the story is another good one. He explains: “The customer wanted to work with a CSP – a very large CSP, in this case, with operations in 20-plus markets. And yet this big food and beverage company is in 49 markets.”

So far, so interesting; but ‘multinational’ is a relative term, which rarely means ‘global’ in telecoms. This kind of 49-into-20 equation must be familiar whenever a multi-market operator matches up with a multi-market manufacturer. “Yes, so we used vertical spectrum, sometimes, and other partnerships that we have for spectrum, sometimes – and then for seven sites in seven markets, where there was no spectrum at all, we used MulteFire.”

Daeuble says: “This company wanted the same network across all 49 countries, and MulteFire was the only way to do that. So MulteFire is very relevant to accelerate deployments. Nokia expanded into eight new countries with MulteFire last quarter (Q4 2021). It is starting to see good traction, opening up temporary networks, as well, for outdoor events and construction sites. It is starting to matter, because it allows us to add capacity, as well.”

This is the draw of the MulteFire project, which has found its way back into the 3GPP agenda with development of 5G NR-U for 5G in unlicensed spectrum. Daeuble says Spanish regulator CNMC has just released a 20MHz tranche of 2.3 GHz spectrum for localised 5G. We are confused; we can’t find a public reference, and ABI Research says 3x10MHz blocks at 2.6 GHz are available for Spanish enterprises. No matter, the argument is the same.

He explains: “But that [2.3 GHz provision] is 20MHz, which will only get you so far. With MulteFire, you can add a few small cells into a building, and have extra capacity… We can go way over a kilometre with MulteFire, while Wi-Fi stops at 400 metres. It is really powerful – same spectrum, same band, higher coverage. Wi-Fi has an edge in terms of bandwidth, but Industry 4.0 wants capacity and reliability, and MulteFire delivers.”

Just as an aside; MulteFire was supposed to be a group effort, right? “It was supposed to be, originally, yes,” responds Daeuble. And it appears to be again, because of NR-U. “Yes.” And what about the old MulteFire vision for LTE in unlicensed spectrum; have the others pricked up their ears now? “They are starting to – and they will when they see we have a 49-market deal, or when they see we can deploy in this construction channel, and they can’t.”

Just as an aside; MulteFire was supposed to be a group effort, right? “It was supposed to be, originally, yes,” responds Daeuble. And it appears to be again, because of NR-U. “Yes.” And what about the old MulteFire vision for LTE in unlicensed spectrum; have the others pricked up their ears now? “They are starting to – and they will when they see we have a 49-market deal, or when they see we can deploy in this construction channel, and they can’t.”

He explains the proposition in the context of Nokia’s own grab for scale. “The aim was always to get a second [spectrum] source for enterprises. Because you always need more spectrum; more capacity, more bandwidth. We want to show that unlicensed spectrum is useful, and show the potential for 5G NR-U. And we lead in private wireless, and we want to maintain that lead – to make it mass-market,” he says.

“Because let’s be honest, we have barely scratched the surface. We know there are 15 million sites out there (page 3). And to get to that, even to chase our own part of that market, we need a cookie-cutter approach, as much as possible. Which is why we are working on these segment blueprints, as well.” We will come back to these cookie-cutter blueprints – in this narrative, momentarily, and in a separate review of the MFA story on pages 20-21.

But we should park the MulteFire/MFA discussion. Nokia’s spectrum pursuits have seen it develop operator partners and industrial devices around random rights holders (like Edzcom in Finland and Sweden), plus “exotic” frequencies besides; notably the low-range 410 MHz and 450 MHz bands, used for wider-area private networks in the utilities sector, and the 1600 MHz L-Band (B24), formerly for satellite comms, via a deal with Ligado Networks in the US.

“We are signing up more spectrum partners, which are not CSPs, which own some spectrum, typically exotic spectrum, for satellite and other things. But there are no devices, so we’re installing modems to support these exotic bands,” says Daeuble. The L-Band is a boon for ports, potentially, on the grounds the military, as the incumbent rights holder in CBRS spectrum, takes precedence for spectrum access along the US coast, mostly for radar usage.

“You can’t have everything stop for a few seconds while you change the channel. We are using Ligado’s band [to cover that], to keep the port running, and we are developing devices for it.” But these seem like workarounds, albeit smart ones, to the enduring challenges of spectrum fragmentation and device scarcity. Nokia is finding a way to make 5G work for industry, but hard graft is not the answer. At some point, Industry 4.0 needs to get easier.

This is article is taken from a recent editorial report on Industrial 5G Innovation – From Setting Standard to Becoming Standard; the previous instalment in this serialised version of the report is available here. Subsequent instalments are listed below (linking either to the original report, or to web articles, as they are available). The report includes additional features and interviews, and is available here. A webinar on the same topic is also available, here, with speakers from ABI Research, MFA, Schneider Electric, and Vodafone.

The trouble with private 5G for Industry 4.0 | Part 1 – the standard

The trouble with private 5G for Industry 4.0 | Part 2 – the devices

The trouble with private 5G for Industry 4.0 | Part 3 – the spectrum

The trouble with private 5G for Industry 4.0 | Part 4 – the features

The trouble with private 5G for Industry 4.0 | Part 5 – the system

The trouble with private 5G for Industry 4.0 | Part 6 – the channel