France-based virtual operator Transatel, busily offering somehow-unfashionable local MVNO and MVNE services in Europe for two decades already, has a second (actually, third and fourth) life, suddenly, in the global IoT game – which has become even racier in recent years with its acquisition by NTT Group, and its strategic positioning as a roaming extension for telematics and logistics apps sprung from the Japanese group’s modish private 5G play.

“That is the ultimate business case, and something we are actively discussing [with customers] in Europe and the US,” says Jacques Bonifay, chief executive at Transatel. He explains the concept in automotive production, where Transatel has a decent line-of-business already, frequently up against Vodafone, for the supply of telematics airtime, and where NTT is actively pushing private cellular for factory connectivity and automation.

“That idea that you make a car in a smart factory using a private 5G private network, and the software in the car has to be updated at the end of the assembly line, and then tested with the public network – and the car is parked for days or months, and then located and shipped and sold, and driven around the countryside, connected to the public network, and eventually, returned to the dealership for work because of a diagnostics alert.”

The point is that cars, like most consumer products, are increasingly connected, of course, both on the line and on the road – and require a cross of private and public cellular connectivity along the way. Transatel, itself, has travelled its own winding path to get to this point, notes Bonifay, who co-founded the business with deputy-chief Bertrand Salomon 22 years ago. But that is the way for any good startup, he says – adapt to survive, and to succeed.

“This is an entrepreneurial story,” he says. “You start with an idea, and you are generally wrong – so you change.” We should rewind, briefly; Transatel started as a virtual operator (MVNO) in its own right, piggybacking on local carrier networks in France, and then Belgium and the UK. This was the 2G-era, just as 3G was being talked-up (including, famously in the UK, by a galactico called David Beckham) to make the internet mobile.

It was a decade before LTE (plus Apple) actually did so. IoT did not even exist, as a buzzword tech-term, at least; industry-geared 5G, using privately-owned infrastructure in privately-owned spectrum, was a pipedream. Which gives a sense of history, and its forward-march in telecoms. Transatel moved with the times, reflects Bonifay. “The MVNO business is tough; the mortality rate is high. Your biggest supplier is also your biggest competitor,” he says.

“You have to adapt; our first MVNO was a good wrong-idea at the time, or a wrong good-idea.” So the MVNO model mutated to one of MVNO-enablement (MVNE), selling “turnkey solutions to launch MVNOs”. Transatel now “runs” (enables/manages) more than 100 MVNOs across the same markets in Europe – including, in the UK, Plusnet from BT, CMLink from China Mobile, CTExcel from China Telecom, and abZ from enterprise reseller Abzorb.

Its MVNO/E business has 1.2 million subscribers, and €30 million of revenue – from a forecast turnover of €52 million in 2022. “It is our first business, and our biggest and most profitable one,” says Bonifay. The balance, of €22 million, comes from its newer IoT affairs, started nine years ago – in the early days of LTE, when IoT was just M2M – as a global data MVNO propped up on cellular roaming deals via direct MNO ties and its own MVNO/E partnes.

“We were thinking about going into the fixed business, and then, for various reasons, had this idea about a worldwide data MVNO – to be freer in the market, to have fairer competition. We had this 901-37 mobile (country/network) code (MCC/MNC ‘tuple’), and core infrastructure, because we had a full MVNO in France, and we were tired of being always-dependent on the MNOs – who could kill us at any time,” says Bonifay.

The company now offers IoT airtime in 190-odd countries. But the logic, originally, for an embedded global data SIM was to connect laptops and tablets, mostly for business travellers to get online cheaply and securely in hotels and airports. “It is always a problem of timing; it is still surprising to me that we have been more successful with connected cars than connected PCs,” he says. “Maybe I was just eight-years too soon – the time will come.”

Its IoT business splits into three units: automotive IoT, supplying in-car connectivity for telematics and ‘infotainment’, where Transatel now claims a position as a leading contender next to Vodafone, arguably Europe’s premier telco M2M brand; industrial IoT, providing global airtime for maintenance and localisation services in and out of production and logistics environments, where it also finds itself up against bigger MNO brands, and where its marriage with NTT funds form; and more familiar consumer/prosumer IoT, in line with its original IoT proposition to offer global roaming.

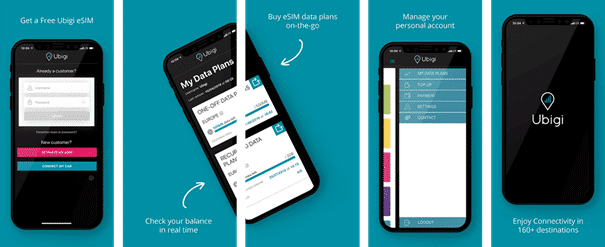

There are some big names on its books. Jaguar Land Rover using Transatel for automotive IoT – for software updates, navigation services, and general in-car connectivity; so is Fiat Chrysler; so is DAF Trucks. Airbus is using it for industrial IoT, to underpin its Skywise cloud platform, resold to airlines to collect data from aircraft during layovers. In the case of the first and last disciplines, Transatel is working via its Ubigi consumer embedded-SIM (eSIM) brand.

“It is this nice little brand – in your car or on your travel SIM. Jaguar Land Rover did not want to use its own brand; it wanted us to come with a brand. If you put a big MNO brand inside a Jaguar, then that is very invasive. Ubigi is not invasive; it is discrete – and can be switched easily to Jaguar or Fiat, or whatever, whenever the customer wants,” he explains. The consumer eSIM proposition works just by downloading the Ubigi app, on a phone or laptop.

Interestingly, Bonifay says a decent chunk of the company’s travel-SIM traffic is generated in-market, because of competitive local rates, and never actually crosses borders for foreign roaming. “Fifty percent of the traffic in the US is generated by Americans using the service in America; it is about the same in France, and a bit lower, about 30 percent, in the UK – which shows the service makes sense locally as well.”

But the discipline, itself, is the same with each segment, sas Bonifay. “IoT likes to talk about ‘verticals’; but, actually, by providing secure global cellular connectivity, we are horizontal,” he says, explaining a fleet-management case for a million vehicles with an unnamed customer.

“So I am invoicing for logistics data every day, but I am also invoicing every driver. So I have this B2B and B2C capability – and I can also bill third parties, such as insurance companies.”

Insurance companies want the data, too, he says, to help to authorise claims. He adds: “So I am not really into predictive maintenance, or geo-localisation, as such – although we are enabling those applications. But this additional B2C capability makes the difference – it is what the likes of Jaguar Land Rover likes about us, that we manage the consumer relationship as well.”

Which is interesting, of course; but Enterprise IoT Insights is most interested in this industrial IoT piece, as it crosses into the automotive IoT segment in manufacturing, and jigsaws with NTT’s newer private 5G play – in this “ultimate use-case” scenario. “I am not selling private networks,” says Bonifay. “What I am selling is worldwide connectivity, on public networks. It is totally compatible. NTT is selling private networks, and we are working with it to win deals.”

The Covid-19 pandemic got in the way, he says; it is only now, three years after NTT swooped, that Transatel finds itself working more closely with its new parent to knit public and private cellular together for enterprise customers. “NTT is really pushing on private networks, and it likes our SIM solution because it brings connectivity inside the factory, on the private network, and also outside of it, when the product goes on the road, anywhere in the world.”

Automotive production is the obvious sweet-spot. NTT-style private LTE and 5G networks are not useful only for factories, to make them ‘smarter’, but also for parking lots and dealerships, under the direct or indirect control of the manufacturing companies, to bring them closer into the fold. Bonifay says intensive software flashing of large fleets of vehicles, fresh off the production line in car parks, have been known to ‘down’ the public network completely.

The private network needs to go outside of the factory, too, he says. There is a case it should be also replicated in the dealership – taking cars for preemptive work, down in a “third-floor basement workshop”, because of a diagnostic alert over a public network. “You know the problem before the car goes in,” he says. “And you want connectivity deep inside the dealership – so a private network is needed, and maybe a whole system of private networks exists.”

He adds: “There is a continuum, across factories, and car parks, and dealerships – and then the car goes out onto the public network at every point in between.” Transatel is going mob-handed with NTT into RFQs with “very big names in the automotive industry”, says Bonifay, notably in Japan and Germany. The same model works in aircraft manufacturing, and elsewhere. He explains his company’s private/public IoT network integration work with Airbus.

“The plane is assembled on the line in Toulouse, in France, but the parts are manufactured in Spain and Germany. So they move around, and they need to be connected and located. Sometimes they are in a factory on a private network, and sometimes they are on the road, or in the airport. So, again, you need a solution that works inside and outside the factory,” he says. But Airbus, it might be noted, is taking a private network from Ericsson, not from NTT.

Bonifay responds: “We are open to work with any private network provider; we can work with any of NTT’s competitors, as well. In the case of Airbus, we did the demo on the Ericsson network. But Airbus is directing that project – it decides what to do.” That open relationship with NTT is important, he says, and what sets Transatel apart from certain other high-profile MVNOs offering global IoT connectivity in the market – notably Germany-based 1NCE.

Bonifay likes the 1NCE model, and its impact, he says, but he also makes clear they are serving different IoT markets, with 1NCE more originally-focused on traditional low-power IoT for sensor solutions (“very small usage for a very long time”), and Transatel moving down the gears, from a legacy M2M start-point of cellular broadband roaming – as traditionally required for automotive telematics, fleet management, and in-car infotainment.

He responds: “Jaguar Land Rover [traffic] is probably about 150MB per month [per SIM]. But all the new RFQs from automotive manufacturers specify more like 2GB per month. The average Ubigi SIM for consumers carries about 1.5GB per month – which is, basically, someone using a smartphone or laptop. We have cases with very low usage, because we don’t refuse business, but our focus is more on mobile broadband.”

At the same time, as per its opportunism, Transatel is also “opening up” global low-power wide-area (LPWA) roaming on LTE-M and NB-IoT networks for ‘massive IoT’ projects – in line with the gathering supply of public infrastructure and demand from enterprise customers. “Because I have the requests,” says Bonifay. “But, yes, it is true that we have prioritised 5G over LTE-M, for example – as an upgrade path for LTE business.”

So far, Transatel is offering full-fat 5G-based IoT in 25 countries, he says. It is offering low-power LTE-M based IoT in 20 countries, and counting; NB-IoT is a 2023 project. The point about independence, even with NTT in position, is the other differentiator for Transatel in the crowded IoT MVNO space, he says. “1NCE is not completely independent because it has Deutsche Telekom and Softbank,” he says, referring to the German outfit’s big MNO investors.

It is the same with Irish automotive specialist Cubic Telecom, he says, in which German car manufacturer Audi has a stake (via its Audi Electronics Venture investment arm). These are partisan investors, he suggests, rooted in the same service discipline (in telecoms and automotive, respectively). But, hang on; what about telecoms giant NTT? “But it is NTT; it is not NTT Docomo. I’ve got NTT Group – which is a big IT company.”

He goes on: “I mean, NTT wants to become one of the biggest networks and IT services companies worldwide. So far, Transatel has retained a high degree of autonomy so we can be agile while also benefitting from the power of the group – especially when addressing Japanese car OEMs.”

And what about versus the traditional MNOs? Because big telcos have their own roaming deals, to provide global connectivity for straight person-oriented broadband or machine-led broadband and narrowband; plus, in local markets, they have long-trumpeted public/private network integration (PNI-NPN) as a golden use case for carrier-led enterprise IoT. “MVNOs have a competitive advantage because we are more global, by nature,” he responds.

“And because we are independent from mobile operators, as well – which is important, especially, when you want to benefit from multiple networks in different countries. Really, the operators need to come up with more creative ideas, and more innovation; otherwise they are useless.” Ouch. There is evidence, increasingly, that traditional operators have either given up on IoT, or got creative with it, by delegating to smaller global MVNOs, like Transatel and 1NCE.

Certainly, this is what their investments in these firms suggest. Is that right? Does Bonifay perceive there to be a gradual outsourcing of IoT by the operator set? “There are different positions and strategies. Yes, some of them have decided to outsource to smaller companies, either as shareholders or as partners. But there are plenty of big operators that still think they can do everything, even though they only really exist as regional entities.”

He suggests that BT, characterised as a progressive, is “in a way” reliant on Transatel for IoT roaming – on the grounds BT is “only in the UK, and IoT is a global market”. He says: “It expects me to bring bigger business, and so it was very happy, for example, when we introduced Airbus.” There are too many dots to join, here; this “entrepreneurial story” has gone long-enough. What about this private/public enterprise roaming market, then?

Just rewind to the start; that “ultimate business case”, for a car roaming on private and public infrastructure, from the factory to the showroom, to the workshop, and all the roads between – how big is that opportunity, actually, now and in the future? “I don’t know; I don’t have a crystal ball. It is too early to say. But I can tell you that enterprises, like Airbus and Jaguar Land Rover, are interested. And I can tell you that it is big enough for me – to focus on now.”

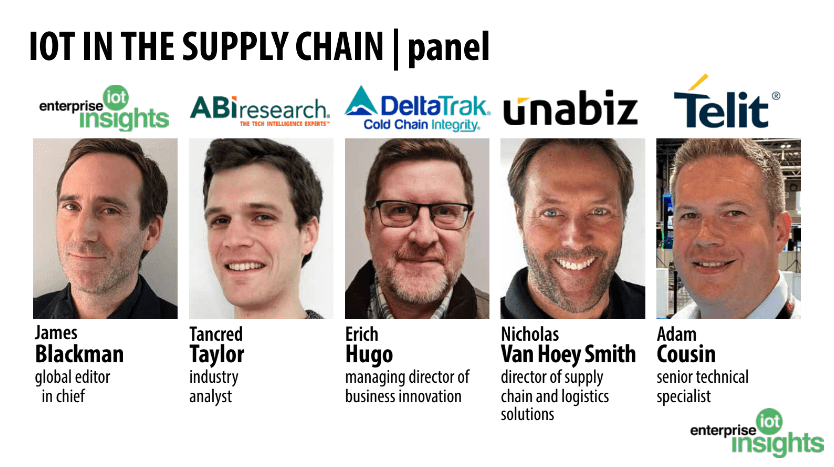

For more on IoT tracking and roaming on public and private networks, join the upcoming editorial webinar on November 29, on: IoT in the Supply Chain and Logistics Industry – how IoT grew up and got real, in the hardest industry of them all. The session features a crack no-holds-barred speaker lineup, with panellists from ABI Researchm, DeltaTrak, Telit, and UnaBiz Group. Sign up here, or by clicking on the images below.