Clearly, IoT solutions should be designed for whatever is to be tracked. In high-value and low-volume cases, this may be the goods themselves. More likely, IoT solutions will need to be architected to fit with shorter-life crates and pallets or longer-life containers. Where a vehicle is tracked, the IoT solution will take a power feed from the engine – and so lower-power IoT technologies are not required, and regular cellular will get the job done.

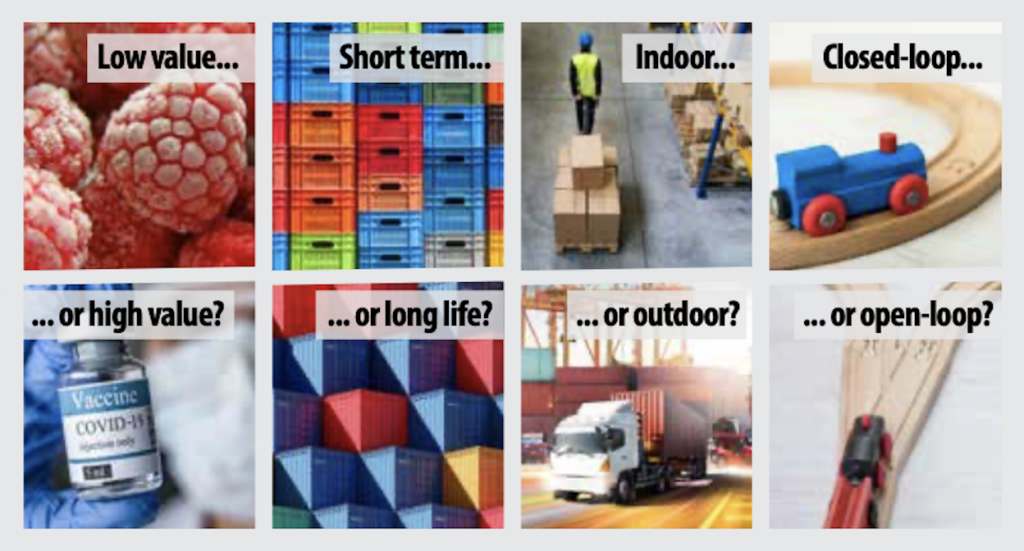

As well as identifying what a tracker will be attached to, a number of other questions can help to discern the technological makeup of an IoT solution, and the spend on it. These include the value of the goods (low or high), the life of the tracker (short or long), the coverage area (indoor or outdoor), and the familiarity of the tracking journey (closed or open loop). Cellular tends to be the answer to the second of all these questions.

But, in every case, no matter the value of the asset, business logic says to balance optimal performance and optimal cost – and, generally, a combination of short- and long-range wireless technologies will be adopted. Tancred Taylor, industry analyst at ABI Research, comments: “People think it is a question of wide-area technology or short-range technology, as if they are in opposition. But that is changing.”

He goes on: “Enterprises are looking at the whole supply-chain web, to leverage the best short-range devices – tags, trackers, labels – to connect to wide-area gateways so they don’t need to put a wide-area device on everything, and how to use satellite strategically, as a backup for when they are out of terrestrial coverage.” Let us consider this statement more, as well as the original explanation, simply, that the use case will define the final tech solution.

…

Architectural decisions about the roles of device-to-cloud wide-area IoT and point-to-point short-range IoT for simple low-power tracking solutions still come down to a tradeoff between function and cost – which, in the end, always comes down to the nature of the cargo. Because even with cheaper parts and smarter pricing, a cellular IoT module still costs more than an RFID tag or a BLE beacon, and the business case has to be made every time.

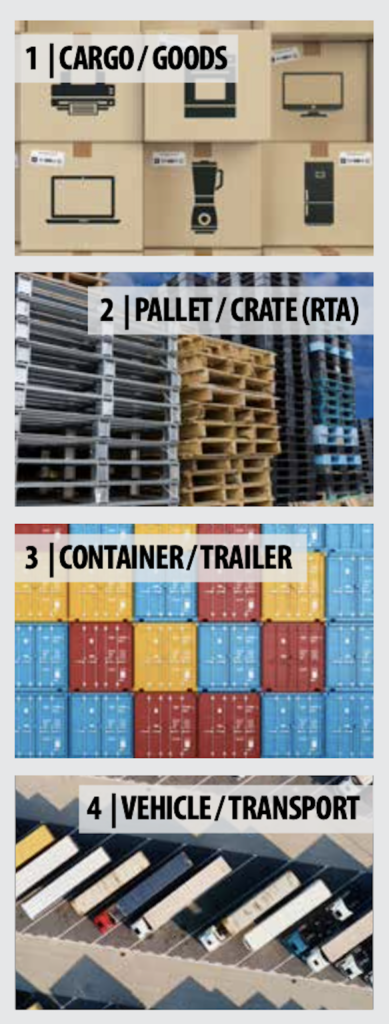

“The question is how to bring the cost of the wide-area trackers down to the point you can put them on more things, or how to link telematics systems just with tags,” explains Taylor. The related question, about the asset itself, is not just about the type of cargo, of course – because the tracker might also, and more likely, be attached to a returnable pallet or crate, or a long-life shipping container, or simply tracked with the vehicle itself. In simple terms, there are four places to attach an IoT tracking unit, as per the image, right.

“All those require a different connectivity solution,” says Taylor. “If you are attaching a tracker to the cargo itself, you are generally looking at shorter ‘journeys’ – a battery life of 30 to 40 days, say, and good connectivity at all points. So you are probably looking at cellular because of the coverage – or BLE tags connecting to a cellular gateway. Again, it depends what you need. You need pretty good [positioning] with higher-value assets and less good with lower-value assets; and then a few sensors for some kind of monitoring.”

Returnable transport assets (RTAs), like pallets and crates, require “something entirely different”, says Taylor. Form factor and tough-factor are important considerations, clearly, as is the ultimate mix of sensor hardware and analytics software; but the first priority, arguably, in any battery-operated IoT unit is power efficiency, to match the life of the asset and bookend its rate of return. For a tracker in a shipping container, the battery has to last “even longer”, says Taylor. But these four tracker options hinge on other factors, apart from just the value of the original cargo, as per the image below.

The parallel consideration is about indoor and outdoor connectivity, and the urgency and frequency of data transmissions to the cloud. “You might only need indoor connectivity, in a warehouse or a campus, in which case a proprietary private network technology might be good enough,” he explains. “Or you might need it to roam all over the place in an open-loop supply chain, or track it in case it is stolen, and so, again, you might want cellular.”

Distinctions should be drawn between closed- and open-loop supply chains, where an asset is either travelling with known carriers to known destinations – sometimes even just within an enterprise environment – or else going who-knows-where in the wider world. Short-range IoT is a complete option in a privately-controlled closed-loop envi- ronment; a wide-area wireless link is required outside of a private network, in both closed- and open-loop chains.

“You know where the goods are in a closed-loop supply chain, whether they are in your factory or warehouse, or going between, or onto a retailer. You might get away with RFID or BLE tags with a fixed gateway in a closed-loop. You can’t do that in an open-loop, because you don’t know where the goods are, necessarily, and you’re in trouble as soon as you don’t have a reader to read the device. So you need a parent device to get the data to the cloud.”

Taylor explains: “A lot of the focus initially is on connecting internal closed-loop supply chains. Because it is easier to do, and cheaper – just with short-range tags, and maybe a cellular gateway to get the signal out, or with a cellular tracker on every tenth pallet because you are tracking flows, rather than individual assets. An open-loop chain gener- ally requires a wide-area technology, and is much harder and slower to take off.”

That said, some are doing just that; Taylor points to the example of Australian logistics outfit Brambles, parent to pallet-pooling company CHEP, plus a new digital solutions division called BXB Digital, which is developing proprietary IoT for a global fleet of 360 million pallets, crates, and containers. It has so far deployed 250,000 pallets with “autonomous tracking” in the UK and Canada; another 300,000 are due in North America in the next 18 months.

Helen Lane, chief digital officer at Brambles, says: “We aim to remove the need to think about pallets at all. We will use data to automate processes and predict challeng- es… [to] enable a frictionless experience. Our ambition is to use the same analytics to deliver a better-Brambles, to shine a light on our customers’ supply chains… [and] to provide products and services that address shared industry problems.” (See full interview here.)

For Taylor, the challenge for the supply chain sector at present is mostly a straight IoT-style exercise, just to connect the dots, crossing over into siloed company systems – even before pulling them together in analytics engines in software dashboards. He says: “Customers don’t have a lot of digitalization in the first place – whether at the edge, or a systems level. So the discipline just now is to string things together, and fill in the gaps.”