Some of the best ideas in IoT… Scratch that; some of the most important innovations in the whole tech game… Actually, scratch all of that; if everything in the end is going to be connected in an internet-of-things (whatever that is), then some of the best ideas, full stop, come from smaller-scale IoT developer events. Right? Because that is where the little revelations, which one day drive big revolutions, are first presented and debated.

The non-cellular IoT industry has always been good at this. Traditionally, it was the big heads at Sigfox that used to hand out bare-bones prototypes at trade shows to show how IoT is a race to the bottom (only to find their big mouths got them in trouble, and their race was run). But the opposite LoRaWAN crowd, which has emerged in finer fettle from the sector’s big wobble 18 months ago, showed more valuable innovation in Amsterdam this week.

The eureka moment at The Things Conference in the Dutch capital was from France-based Dracula Technologies, which presented its energy-sucking low-light solution for passive (battery-less) LoRaWAN, and also announced a new production facility is set to go live with capacity for 150 million commercial units per year. So, yes, big news – to the point the TTI-guys, hosting the Amsterdam show, spot-lit this dim-lit tech in their opening keynote.

“We are going to see less power but more life – more data for the same money, which… completely changes the economics,” said Johan Stokking, chief technology officer at The Things Industries (TTI), speaking at the event in a two-hander with his co-founder Wienke Giezeman, chief executive at the firm. Giezeman presented some more envelope maths: three-times battery-life means three-times asset-life, which equals three-times returns.

“Your returns kind-of triple. Which is really, really disruptive economics. Because if you write-off your IoT investment in three or four years, then it is basically an IT investment. The moment that that sensor can send data for a period of more than 10 years, then it becomes more of an infrastructure investment. So this completely changes the game… In two to three years, there will be no LoRaWAN sensors without this kind of energy harvesting technology,” he said.

Which is big talk, and also hugely exciting for the whole digital-change game; anecdotally, plenty of product reps on the stands in Amsterdam expressed deep concern about how massive-scale IoT is a massive-scale environmental problem, if the batteries are included. In his own keynote, Roelof Koopmans, once in charge of strategic alliances at Semtech, now in charge of business development at Dracula Technologies, pointed to EU-backed research about IoT’s dirty secret.

Because it turns out (of course) that IoT, the tech movement that is supposed to save the planet, is destroying the planet. About 78 million batteries from battery-powered IoT devices will be dumped globally every day by 2025 – if nothing is done about it. “Seventy-eight million batteries. A day. Right? Is that sustainable? Definitely not,” said Koopmans in Amsterdam. “The whole IoT ecosystem has an obligation to think more sustainably.”

For the LoRaWAN-end of it, Dracula Technologies claims to have a “very unique” and “very disruptive” solution, according to Giezeman and Koopmans, respectively. So what is it, and how does it work? How does IoT become an infrastructure investment, and how does it become green? Well, it probably requires an additional deep-tech workshop if you are a developer with serious green credentials, but the RCR explanation goes something like this…

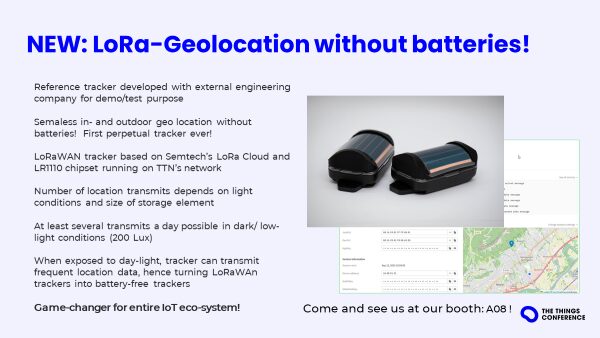

Dracula Technologies has developed a tracker that runs on an organic photovoltaic (OPV) solar cell – which can be printed in any size, depending on the required power output, onto an 0.3mm adhesive sticker on a regular inkjet printer using special OPV ink. The OPV LoRaWAN unit – which uses a reference module from Semtech and a cloud stack from TTI, and engineering knowhow from some unnamed French manufacturer – works in low light in dark rooms.

OPV technology draws power in the murkiest conditions, such as in warehouses or (“lights-out”) factories, where the luminous flux per unit area (lux), which measures illuminance, goes as low as 500. As a frame of reference, outdoor light registers at closer to 10,000 lux. “Five hundred lux is where it gets challenging,” said Koopmans. “If you design a [passive green] room sensor, or air quality sensor, then it has to be able to work right in low-light conditions.”

The solution from Dracula Technologies – branded LAYER, as an acronym for ‘light as your energetic response’, and presented for marketing purposes as a bat-shaped OPV printout – works at 200 lux, and even down to 100 lux, said Koopmans. Actually, it needs just a flash of murky light (“as low as one lux, right – which is almost completely dark”) to wake up and send out a signal. “It will harvest at that point, and blink, and send data to a LoRaWAN gateway.”

Koopmans explained: “OPV is also the greenest of photovoltaic technologies. Competitors claim to have green tech, but they are not as green as you think. Silicon-based photovoltaic cells, for example… are not sustainable. Because if you use organic materials like lead or other rare-earth materials, then you are not sustainable. OPV is the way to go. And [for lots of so-called green solutions]… the energy balance is completely out of whack.”

He added: “There are no rare earth metals in this. There are no toxic materials… It is all recyclable… Many of the manufacturers that approach us say they have customers… that only want green sensors. They don’t want anything that is not recyclable. So the pressure is coming from the market – from customers wanting this industry to produce sensors that are fully green, and not just greenwashed.”

Dracula Technologies has 30 staff in France, and capital funding of €25 million from “strategic investors” like Semtech and from “financial investors” like BPI in France. It is building a brand new production facility – “and it’s really huge,” said Koopmans. “We will have a capacity of 150 million units a year from next year (January 2024). We are ready to roll with this.” But the pitch is not just about sustainability, clearly; it claims a litany of business gains.

These include commercial viability, as per Giezeman’s statement at the top of the piece. On stage in Amsterdam, Koopmans suggested an IoT sensor solution might only cost €100 upfront, but that its total cost (TCO) through the life of its service is likely to be closer to €500 to a customer – mostly because of truck-rolls associated with manual interventions (“deployment, onboarding, management, battery replacement”).

And in the end, for massive IoT in the field, battery replacements will never happen in many cases. Which means massive IoT will fail in many cases. Koopmans said: “We have talked to so many logistics companies that would love to deploy a LoRaWAN sensor, which have said they can’t do millions of units on a global scale if they are battery-powered. They have to be passive. So here we are – a passive LoRaWAN device that provides geolocation indoors and outdoors.”

The solution builds on the initial power gains made by Semtech’s LR1110 / LoRa Edge platform, released a couple of years back, whose trick was to take the compute burden (to calculate positional data from GNSS and Wi-Fi scans) out of the device and into the cloud – in order to extend the battery life of sensors. The integration of an OPV power source into an ultra low-power LR1110 solution, which is not required to do any edge computing, is the key.

It brings an 80 percent “cost efficiency” to the customer, according to Koopmans – which presumably tots-up savings from cheaper hardware and extended life. Dracula Technologies promises 10 years of consistent “power performance” indoors, dropping to five years outdoors in the glare of the day. Eliminating the battery – into a printable OPV power-harvesting label – means developers can experiment more easily with the form factor of their solutions.

The size of the printout depends on the number of OPV cells, which is dictated by the lighting conditions and the power requirements. “The number of cells determines the voltage, and the size of the cells determines the current,” explained Koopmans. The firm will print the OPV labels in any shape or form. “We are not stuck with any sort of shapes that come off a roll, or whatever. The production process is completely flexible.”

He said: “The darker it gets, the harder it gets. Which is where Dracula comes in… We have demonstrated this can work in very low light [venues]… in logistics warehouses and distribution centres where you have pallets, boxes, cranes or whatever operating in the dark. These assets can now be located without batteries. It is a complete game changer.”