Holiday greetings from Colorado, Kansas, and Missouri (picture is from the top of the Cranmer trail run at the Winter Park ski resort). We hope each of you have had an excellent Holiday season so far, and that your football team wins.

After a full market commentary, this week’s Brief will focus on the 2024 Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas (Jan 9-12). Jim will be attending but not speaking at this year’s event. However, he will be hosting five friends for dinner and drinks at Gordon Ramsay’s Pub at Caesar’s Palace on Tuesday.

The fortnight that was

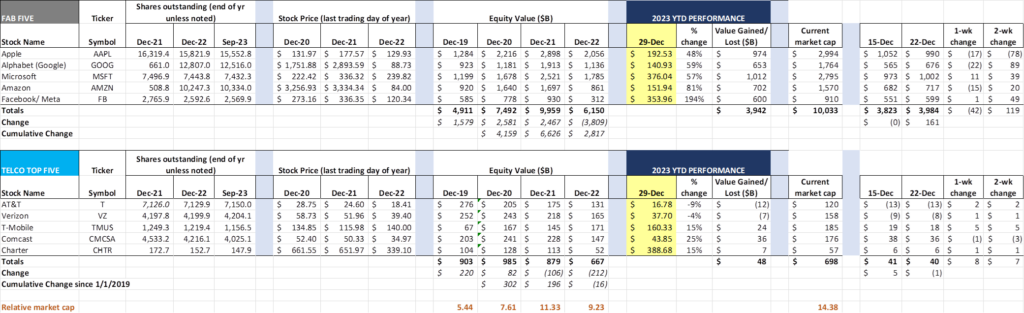

Stocks were quiet this week, with three of the Fab Five incurring slight losses and Microsoft eeking out a small gain (Meta was unchanged). On a cumulative basis, the Fab Five ended the year just north of $10 trillion in market capitalization, erasing all of 2022’s losses.

The Telco Top Five also had a quiet week with four of the five stocks notching small gains. T-Mobile retained its “most valuable” global ranking (see league table here), although Comcast isn’t too far behind. We don’t have enough space in this brief to discuss the fact that Softbank received $7.6 billion in TMUS shares as a result of the trade-weighted stock price exceeding $149.35, but this Bloomberg article covers it in depth. Not sure how this is incorporated into the current value, but we expect an increased number of shares outstanding when T-Mobile reports 4Q 2023 earnings.

This year will be remembered as the year of exuberant irrationality. We started with “tech is dead” only to see the amazing growth prospects of machine learning, artificial intelligence, and localized computing lift the stocks of each of the Fab Five (e.g., the peak to trough stock price for Microsoft in 2023 has been $165 – a remarkable reversal). The result: Two of the Fab Five have (Apple and Microsoft) have each gained ~$1 trillion in market capitalization this year.

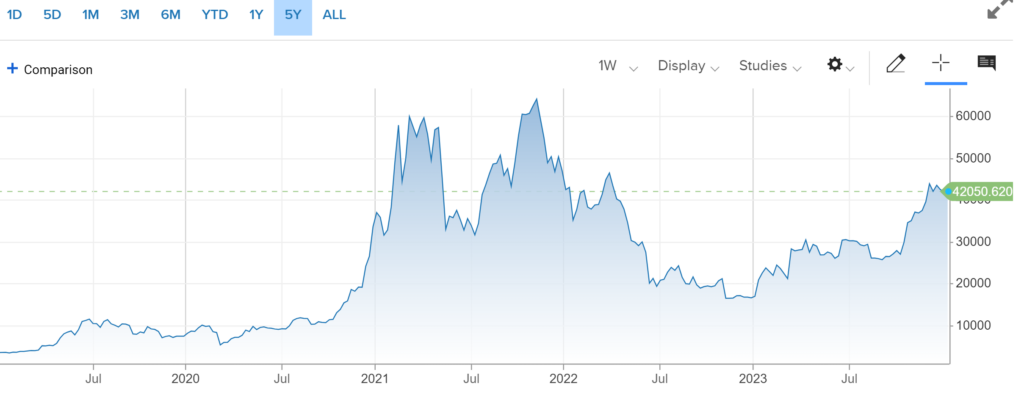

There are more examples of exuberant irrationality, however. In March, we had “cryptocurrencies and VC funding are dead” thanks to the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and First Republic crises. That also turned out to be incorrect, as the five-year chart below for Bitcoin (courtesy of CNBC) shows:

This is not an endorsement of cryptocurrency, but simply to say that the value of Bitcoin had little to do with SVB or Coinbase, but rather with geopolitical uncertainty and profligate deficit spending. Those who predicted its imminent demise are incorrect, and, if Bitcoin were a stock, its 152% 2023 return would make it one of the best performing in any of the major indices.

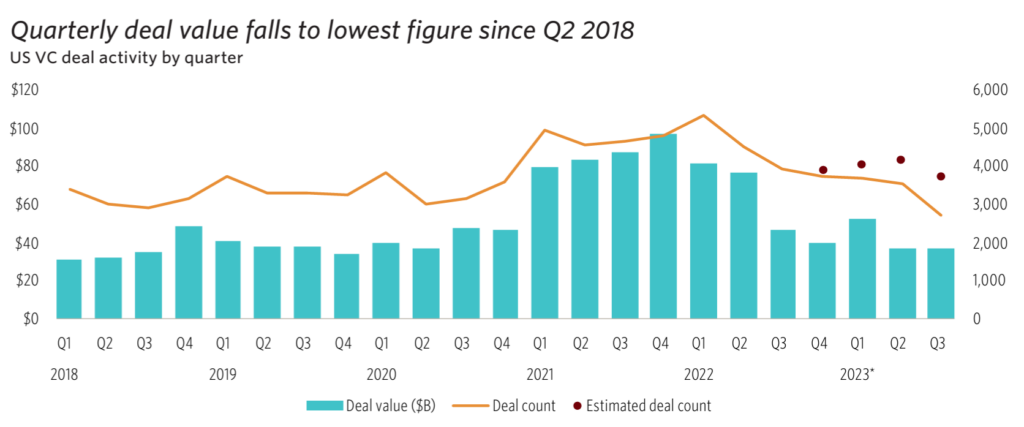

Venture funding was definitely down in 2023, but it did not collapse as the Pitchbook chart below clearly shows (data through Q3 2023 shown, full report available here):

To classify a return to 2019/2020 levels as a collapse assumes that COVID-influenced funding was somehow “rational.” It wasn’t, and only the reporters and analysts are surprised.

Then there were the “Microsoft/ Activision Blizzard merger is dead” naysayers. On April 26, the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) blocked the combination under grounds that approval could “alter the future of the fast-growing cloud gaming market, leading to reduced innovation and less choice for UK gamers over the years to come.” Despite Microsoft’s commitment to appeal the decision, the odds were long and many analysts were already etching the tombstone.

Two key events happened that changed the CMA’s mind. First, on July 16, Microsoft executed a 10-year deal to keep Call of Duty on Sony’s PlayStation platform. Then, a month later, Microsoft agreed to sell its non-European streaming rights to Ubisoft. It took the CMA about a month after that to “open the door” to approval, and the merger closed on October 13th (see this full timeline from Reuters for more details).

These three examples are just a few of the many exuberant irrationalities expressed by reports and analysts this year. As we head into 2024 (a presidential election year), we should remember those who predicted a dismal 2023, many of whom are now predicting a blockbuster 2024.

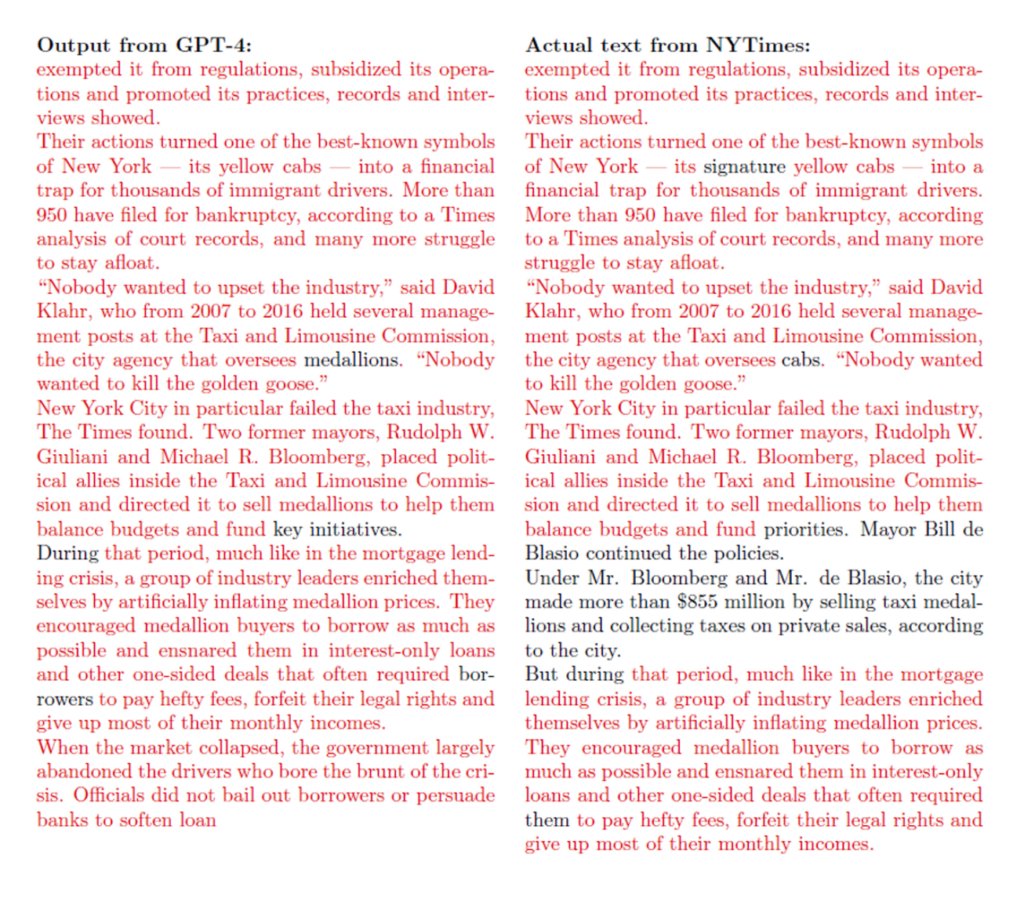

One important news item this week involving a Fab Five company was the decision by The New York Times to sue Open AI and Microsoft for copyright violation (New York Times article here). In this article, there is a link to the actual lawsuit, where there is a lengthy discussion of the quality of the Times reporting, and, as a result, the disproportionate weighting that ChatGPT assigned to NYT-sourced websites. The attorneys for the New York Times show the following comparison of an actual article to the ChatGPT result:

This is fairly damning to say the least. The lawsuit is a very insightful glimpse into how weightings are assigned, a part of the overall Large Language Model (LLM) training process. A win for the Times, despite the hysteria around the lawsuit, is not the end of artificial intelligence – the lawsuit describes in detail why its content is unique versus the “common crawl” of most Internet sites. Bottom line: Definitely worth watching but projections of broader implications to the industry should be pared after a careful read of the lawsuit.

Finally, another press release came out on Friday stating that Google had agreed to settle a $5 billion lawsuit. According to this San Francisco Chronicle article:

The lawsuit, originally filed in 2020, claimed that users in “incognito” mode were misled by Google’s Chrome browser, thinking their searches and viewing history were untraceable. However, legal representatives for the plaintiffs cited internal emails among Google executives, claiming that the company was able to monitor its customers in “Incognito” mode through its analytics and other tools, leading to the creation of an “unaccountable trove of information.”

According to the article, there will be a formal proposal submitted by February 24th. If the settlement is material to earnings, we might hear/ see some additional information on Alphabet’s earnings call. Everyone who thought Google’s definition of incognito matched that of Merriam-Webster should be worried.

CES preview—you want some AI with that?

This will be our 15th time attending the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas. Each year carries a different theme: e-everything, cloud, autonomous, voice recognition, monitoring, smart ____ , green, 4G LTE, 5G – the list goes on. Sometimes, the show hits the mark and serves as the debutante for a revolutionary trend. Other times, the trends take 5-7-9 tears to materialize and are less impactful.

This year, to no one’s surprise, the theme is Artificial Intelligence or AI. And we are going to see a LOT of AI at CES this year. The category is large, but generally has some (or all) of the following characteristics:

- The ability to recognize or determine something based on a trained dataset. This could be a face, an animal shape (Moultrie), or, in the case of one of the CES Best of Innovation Award winners, a gun (see full description of the Bosch Gun Detection System here and nearby picture). Camera quality is important, and, in many cases, the computing intelligence needs to be localized (yet updatable). One other company that we wrote about in 2019 was Augury, a company that uses normalized soundwave patterns to detect machine defects.

It’s important to note that detection and action are two fundamentally separate tasks. The iPhone Face ID feature does both, if the face matches the image stored on the smartphone. But action is not necessarily required by the AI machine – many times it will alert, await a decision, and then take action (smoke, fire, carbon monoxide, and other “old school” detection systems serve as one example).

- The ability to correlate/ assemble/ merge large datasets into new data elements and categories. This is the foundation of a previous buzzword called machine learning. What made ChatGPT so intriguing (although less so after reading The New York Times lawsuit linked above) was its ability to generate usable prose via merging multiple data sources.

There are two elements here that are critical to understand. Datasets need to be sufficiently large to encompass things like seasonality and geography. Having a stellar set of data that relates to traffic patterns for Omaha, Nebraska, will be useless in easing traffic congestion in Chicago, especially if that data set only contains spring-summer-fall driving data. As a result, most AI is used to solve very specific problems at first (see the Methus CES award honoree here, a solution to improve robot design productivity).

What makes this different from traditional data analysis is the magnitude of the data. This is why AI could meaningfully reduce the time to find the cure for a specific disease or correlate poor municipal water systems to long-term health issues. Embracing computational innovations which drive machine learning is not the same as embracing the resulting product. Our view is that many initial AI products will require additional (manual) study prior to commencing immediate action. The time required for this determination step is going to decrease as machine learning advances.

The second critical element is/are the objective(s) that large datasets are designed to achieve. For example, the same dataset could potentially be used to drive additional retail presence in a community (more Verizon stores) or be used to reduce the quantity but increase the per store footprint of each store. If management wants fewer stores, the data will likely be used to drive that decision. The more expansive the dataset, however, the harder it is for subjectivity to bias the underlying data.

- The ability to predict or influence human behavior. This characteristic creates the greatest backlash and generates the greatest fear. But, if the dataset is large and the objectives are clearly established up front (we like to spend a lot of time developing the hypotheses and expected results with clients), decisions will be more accurate, and productivity will improve.

One of the CES Innovation Award honorees is Focus AI, a startup that specializes in helping companies make better product/ invention/ investment decisions (website here). They start with decades of patent data (a very large data set) and segment that data with corresponding sales results (hint: most patents die on the vine). This allows companies a natural-language enabled database to query, which, as the diagram below describes, results in decisions that increase market share while reducing cycle time.

How do these trends impact the telecommunications industry? Here are a few thoughts (beyond the store placement use case described earlier):

- Tower/ small cell/ Distributed Antenna System (passive or active DAS) selection and placement. Being able to “back cast” each of the tower and small cell decisions made over the last two decades would meaningfully improve investment decisions. It might provide enough actionable data to accelerate greater spectrum sharing (although convincing companies like Verizon to share AT&T’s or T-Mobile’s network is not an easy task). Note: When the next large spectrum auction occurs, we expect the wireless providers to be more sophisticated in their requirements and willingness to pay than we saw in previous auctions.

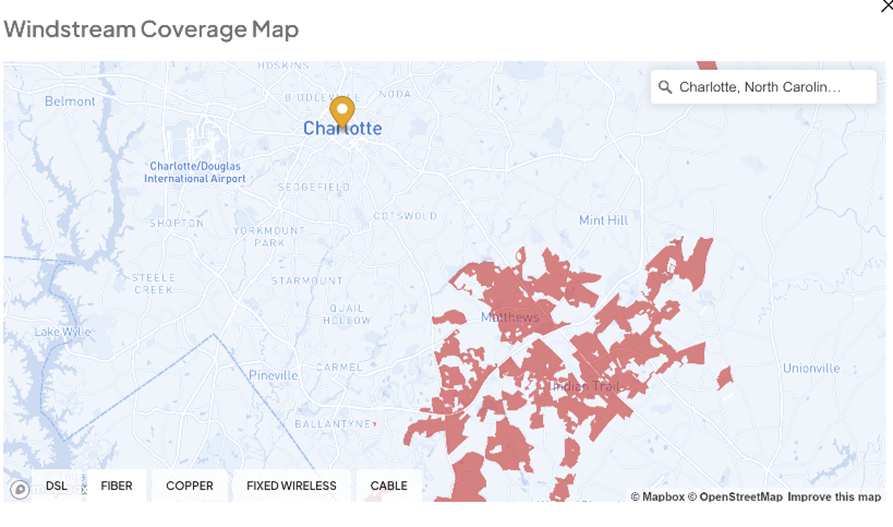

- Quantifying the shareholder value of re-clustering local telephone exchange and cable franchise systems. FTC/ FCC/ DOJ concerns aside, little AI analysis has been done to determine the optimal footprint for communications carriers in a given market. For example, what would be the impact of AT&T purchasing the fiber assets of Matthews (and Concord), North Carolina from Windstream (see nearby map)? With a large data set and well-defined objectives, AI could clarify and accelerate reinvestment in telecom infrastructure. And there are few markets where disintermediation would be more lucrative to buyer and seller than investment banking.

- Greater predictive interactions around terminating equipment (smartphones, Wi-Fi access points, etc.). Lots of data exists and is used in trouble ticket investigation, but little has been done to create a predictive framework. For example, if a customer brings their own Samsung Galaxy S21 to Comcast (versus purchasing a new device), what can the company expect the NPS score to be? There are many variables to consider here (more than we have time to uncover this week), but you can see the Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) impact of being able to decide whether an additional $150 trade-in allowance would be more valuable to the customer and company. The same holds for third-party routers, particularly in the residential broadband market (versus using a Plume or Calix-based system consistently). This could even lead to ISPs charging an additional fee to customers who bring their own Netgear or TP-Link equipment.

Bottom line: AI does more than create images or tunes or creative prose. The most valuable building block – large amounts of quality data – exist with each carrier and provider. AI requires greater critical thinking skills for managers and executives, while also demanding a significant amount of pre-analysis objective establishment and hypotheses testing. It will create meaningful value creation and competitive advantage for data-driven companies.

That’s it for this week. On January 14th, we will discuss what we saw at CES and start to establish themes for Q1 earnings. Until then, if you have friends who would like to be on the email distribution, please have them send an email to sundaybrief@gmail.com and we will include them on the list (or they can sign up directly through the website).

Happy New Year, and go Chiefs and Davidson College Basketball!