The new Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act) sets a common regulatory and legal framework for the development and application of AI in the European Union (EU). It was proposed by the European Commission (EC) in April 2021 and passed in the European Parliament last month (May 2024). At the Digital Enterprise Show in Málaga this week (June 11-13), where AI was all across the stands and keynotes, it was described as a gargantuan undertaking, but presented in an easy summary.

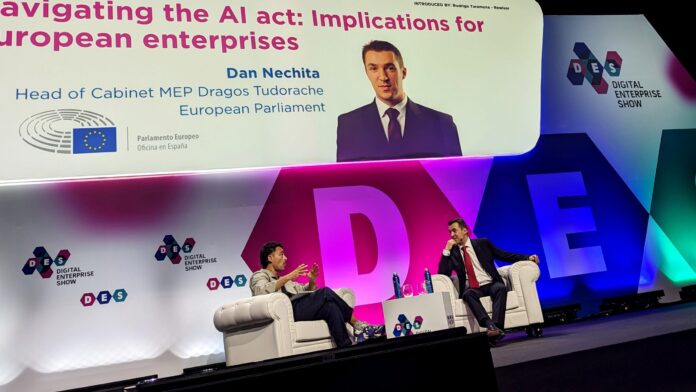

“Can you explain, briefly…?” went the first question to Dan Nechita, Head of Cabinet for Dragoş Tudorache, Member of European Parliament, and the person in charge of shepherding the AI Act through “so many” rounds of votes, before the final one in the parliament on May 21. “Well, it was five years in the making, and about 450 pages,” he responded. “So what is ‘brief’?” But the conversation was a good one, and Nechita explained the EU position very well.

This is summarised below; but a word on the timing first. Nechita said: “We voted on it just a few weeks ago. It was the final-final-final vote – because there were so many leading up to it. It has to be published in the European Journal within the next two or three weeks (by the end of June), and then you have six months for the rules [to come into place], 12 months for the establishment of the AI Office, and 24 months for the high-risk case systems.” All of these elements will be explained.

Beyond this 2026 timeframe, the EU has set another 36-month deadline for the new AI regulations to be applied retrospectively to products that are already in the market. The point is to lighten the regulatory load for vendors of crucial smart devices – like used for medical care, said Nechita – and so to avoid disruptions mainly to public services among member states. The point is that, even with such a long implementation cycle, the AI Act is coming and will have an impact right away.

Nechita, himself, drew comparison with the EU’s early position on data privacy, with its adoption of General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2016 (effective in 2018). The US and UK, notably, are pursuing their own versions, but Nechita reckons the EU version will make its mark. “That’s the Brussels effect, right? Like with the GDPR, where we decided, okay, this is how to protect personal data. GDPR is not perfect, but it has had a global influence. The AI Act will be the same.”

Anyway, here is a timely summary from the Digital Enterprise Show of Nechita’s points about the new AI Act in Europe.

1 | Horizontal and human-centric

In sum, and in response to the initial (and polite) request for a brief summary, Nechita remarked: “The AI Act is a horizontal risk-based human-centric regulation for the protection of health, safety, and fundamental rights.” We will deal more thoroughly with the question of risk below; but, in reverse order, the first point is that the rules are made to guide the development of AI in support of European citizens, and to protect their human rights (“human-centric”), as defined in Europe.

“It’s not for companies, and it’s not for the state,” said Nechita of the protection, and of the correct use of AI also. The second point is that these new rules apply everywhere (“horizontal”) – in all member states and in all industries. “It fills in the gaps in existing European regulation,” he said. Like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the AI Act also applies extraterritorially – to companies outside the EU with users in the EU. Which means it applies, very clearly, to ‘Big Tech’.

But its horizontal reach does not go everywhere, actually; it does not apply to AI systems for military and national security purposes, for instance, which is to be considered separately. It is a corporate tool with a democratic purpose, which does not confer rights on individuals, but regulates original providers and professional users. Its most controversial measure, perhaps, is its treatment of facial recognition in public places, categorised as high-risk but not banned.

Amnesty International, for example, says it does not go far enough, and general usage of facial recognition should be banned. Nechita said: “We’ve [imposed] very strong democratic guardrails… [In that example] we’ve added layers upon layers of safeguards to make sure [applications require] initial authorization – [before] approval of use cases for crime [detection, say], and so on and so on; to make sure [member] states cannot [use AI in ways that] go against our democratic fundamental values.”

2 | Risk-based and future-proofed

“Risk-based means that it only applies in those ways,” said Nechita at the outset in Málaga, before counting the ways, in a simplified format, that the new AI Act classifies risk. The host, Rodrigo Taramona from Spanish tech magazine Rewisor, asked about a “pyramid of risk”, categorising the escalating AI threat from low- to high-level. Nechita responded by describing three categories (low, medium, and high risk). But actually, the AI Act sets out four levels: unacceptable risk, high risk, limited risk, and minimal risk; plus it includes an additional category for general-purpose AI.

Of the four official risk categorisations, applications in the first group (“unacceptable risk”) are banned and applications in the second (“high-risk”) are required to comply with security and transparency obligations, and also go through conformity testing. Limited-risk applications have only transparency obligations, and minimal-risk apps are not regulated. Nechita’s simplified three-tier scale, as presented in Málaga, appears to conflate the first two. He cited “prohibitions” against AI applications that transgress the rights of EU citizens, comparing China’s approach.

He said: “The first rule is prohibition, which is a tool of last resort. It’s not something that is often used in regulation. But it really prohibits the use of AI in ways that we, in Europe, do not accept. The most common example of that is the Chinese social scoring system, where every citizen is assigned a score for how good of a citizen they are, and, based on that score, they get access to services or not, and get promoted [at work] or not, and basically get treated better or worse by the state. Europe doesn’t want that. It contravenes our fundamental values.”

Again, the ‘human-centricity’ of the new regulation was made clear. “The bulk of the regulation applies to AI systems that have a very, very significant impact on the fundamental rights of humans – in employment decisions, in law enforcement, in migration; in places where… the use of the AI can discriminate and, ultimately, put you in jail or deny you a job or social benefits. And all of those are high risk cases [at the top of the pyramid],” he said. And that was the explanation of the top-tier in the three-tier AI risk pyramid, as presented at the Digital Enterprise Show.

The rest of it went to calm the nerves of a nervous audience, perhaps, considering how to deal with the law as EU-based developers and enterprises. Nechita said: “Medium risk cases, going down the pyramid, would be those AI systems that can manipulate or influence people – like chatbots and deep fakes, for example… The act obliges [in those cases] some transparency – so the AI says, ‘Hey, look, I’m an AI; I’m not actually your psychologist’. And then everything else, about 80 percent of the AI systems out there, [are categorised as low-risk].”

Which means, almost, their owners and users do not have to worry, or to think very much. That was the message, at least. “Everybody thinks the act regulates all AI. No, we have not regulated everything. Everything else at the bottom [of the pyramid], where there is no risk, has absolutely no rules – no obligations to comply with,” said Nechita. He was pressed on this; surely there is some light-touch regulation for everyone to think about. “No, I think there is none at all. I think that if you put an AI in agriculture [to help with yield optimisation], for example, then you have no obligations.”

The framework is flexible, and therefore future-proofed, insisted Nechita. The new rules will accommodate the fast-moving AI landscape – at least until Big Tech closes on its endless quest for some kind of artificial general intelligence (AGI), when they may need to be revised. “I would say this, because I am biassed, but we did a pretty good job at future-proofing [the rules],” he said. “[It has] moving parts that can be updated with ‘secondary legislation’. Which is boring EU jargon, but basically means it doesn’t need to go through the whole legislative process.”

He explained: “The EC can update the high-risk case systems, say, to recategorise and remove something [and vice versa]… But the act does not say, ‘you have to do A, B, C’; it says, ‘tell us about A, work with us on B, and be aware of C’. So it is dynamic, and the rules will hold even as AI becomes more powerful. There’s got to be collaboration [for this to work]. Whether or not [the rules are reviewed] when we have something more futuristic like in AGI, we’ll get to that when we get to it. But right now, the regulation doesn’t need to be changed for quite some time.”

3 | Regulation and innovation

So the regulation is done, the message goes; the rules are written. After five years of drafts and votes, it is time to implement them, in phases over the next three years, and for the EU innovation industry to spur EU economic and social markets, said Nechita. “It is time to focus less on how to define the regulation and more on how to implement it. We have the rules; they are human-centric. We are protecting health, safety, and fundamental rights. Good; so let’s now focus on innovation. Let’s invest and support startups and industry. Let’s build European competitiveness in AI.”

Regulators, themselves, can now switch their focus to the “human-centric” application of AI in other sectors, and to grapple with that interpretation in the context of developing defence technologies, for instance – “where these rules don’t necessarily apply, but we still have to make sure technology is safe and in-accordance with our values,” remarked Nechita. In the meantime, the EU has worked to make the regulation compatible with live-or-die vagaries of small tech, while seeking to stop Big Tech from eating democracy.

Nechita explained: “The question about how to balance innovation and regulation always arises. As I said, this act does not regulate everything related to AI. It regulates high-risk cases, mostly. But even there, we considered the needs of startups and SMEs. And for every rule in this 450-page regulation, we took them into account. So the rules are different ; the compliance mechanisms are simplified. If you break the law… the fine [detail] is different for them – so a startup business is not ruined because they didn’t know how to comply.”

Plus, the full proposal specifies a network of ‘sandboxes’ throughout EU member states where startups can test their products for compliance, Nechita noted. A full review, about Testing the AI Act with Europe’s future unicorns, is available here. Again, the message from the regulator is that the new rules are well-designed to control and promote new AI technologies in protection and support of EU citizens, and that they should be considered to present a green light for innovators.

4 | Compliance and enforcement

How is the new AI Act to be enforced? It stipulates the creation of various new institutions to promote cooperation between member states, and to ensure bloc-wide compliance with the regulation. These include a new AI Office and European Artificial Intelligence Board (EAIB). The AI Office in charge of “supervising the very big players,” said Nechita, “who build very powerful systems at the very frontier of AI”. The EAIB is to be composed of one representative from each member state, and tasked with its consistent and effective application across the union.

These two bodies will be complemented by supervisory authorities at national level, banded together as a new Advisory Forum and Scientific Panel, offering guidance variously from the enterprise and academic sectors, plus from civil society. “The central AI Office is… [in charge of] making sure [big corporate AI] systems do not present systemic risks – which, once deployed, do not propagate [that risk] into society. It will work with industry, and has a flexible type of enforcement – so it tests the systems and mandates incident reporting,” said Nechita.

He went on: “So if there is a big incident in GPT5 or GPT6 in the future, say, there’s an obligation to report it to the AI Office – to ensure those very, very big models are safe. And then at the national level, it’s more about enforcing the rules for AI which presents risks to health, safety, and fundamental rights.”

5 | International cooperation

Taramona, his interlocutor in Málaga this week, responded to the new enforcement structure, by remarking: “There’s a saying in Spain: how do you put gates on the countryside?” The implication clearly was that EU-wide consistency is easier said, or constituted in new government instruments, than done. He asked: “You are working to consolidate this as an international playbook. How is that going with EU member states?” Nechita widened the scope, to respond about cooperation on AI with non-EU countries, notably the UK and the US.

He said: “We have stayed in close contact with our partners – with the US and the UK, for example, which have each taken slightly different approaches. The UK, for example, is looking more at national security risks [and] mitigating existential risks. We have tried to coordinate… but we don’t have the same regulatory traditions. Europe has one legal system, and the US and UK have different ones. So we can’t have exactly the same regulation. But we have aimed to have policy interoperability so [these regulations] work together. They’re complimentary.”

He also referenced alignment with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) on the definition of “human-centric” AI. The OECD advocates, as well, for AI that respects human rights and democratic values. Nechita said: “We both started with different definitions, and we have, in the end, finished with very, very similar ones – which the Americans have also embedded in their risk framework at NIST. So we now have a common lexicon – about what we really mean when we talk about AI.”

He went on: “We have the AI Office… and the Americans have set up an AI Safety Institute, and the Brits have something as well, and we’ve [all] started connecting between to make sure we all work together properly. There is a lot of interest in other areas of the world, too. Latin America, and some countries in Africa and Asia, are looking at the European and American models to take the best parts from both. And there’s going to be a lot of work to make sure these are all compatible.”

Click here for more on how telco AI supports network automation and 5G monetization.