AI could save almost a quarter of private-sector workforce time in the UK over the coming decades – equivalent to the annual output of six million workers. So says the Tony Blair Institute (TBI) for Global Change, following up on its July missive to the new Labour government in the UK that the only way out of this mess is with technology. These productivity gains could boost GDP by 5-14 per cent by 2050, it says, brandishing a new research report about the impact of AI on the UK labour market’. AI will create jobs and displace jobs, it writes, and policymakers should manage “these two forces”, just as the government should speed its adoption to grow the UK economy.

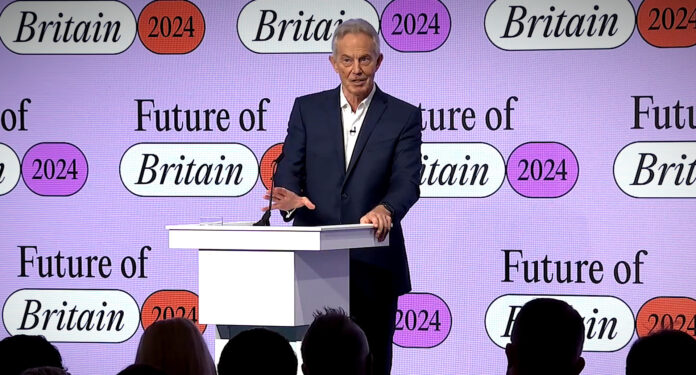

Following a landslide victory in July, an old Labour prime minister told a new Labour prime minister (Sir Blair to Sir Starmer) that the task to fix a broken nation is too massive just with “stable government” and “conventional policies”. He said: “There is only one game-changer: tech revolution”. His UK-based TBI think-tank, like a “McKinsey for world leaders”, reckons AI is the answer, suggesting it could drive £12 billion of “extra fiscal space” per year by the end of this parliamentary term. It might be noted, TBI was criticised for using the GPT-4 large-language model to get its results (to which it also responded), as well as for making “unhelpful and unreliable claims” about what AI can do.

There were other (debateable) stats in there, too. Unabashed, TBI has pressed on, hailing the economic potential for an AI-enabled economy, but warning about a “higher rate of churn and more dynamic pace of change”. It states: “AI could eventually save up to a quarter of the average worker’s time. These time savings could boost productivity growth significantly with TBI estimates suggesting GDP could be 5-14 per cent higher by the middle of the century than a scenario without AI-enabled growth.” The flipside, and the klaxon for the UK government, is that automation, precipitating workforce efficiencies, and potentially economic flex and innovation, will likely also lead to job losses.

It warns: “One to three million jobs could eventually be displaced by AI, though these displacements will not occur all at once, but instead will rise gradually with the pace of AI adoption across the wider economy. On an annual basis… job displacements could peak at between 60,000 and 275,000 jobs a year.” The report sets this in the context of the average number of job losses seen over the past decade in the UK (450,000 per year) and the size of the overall labour force (33 million). It goes on: “This labour substitution effect is only part of the story. AI is likely to create new demand for workers by boosting economic growth and speeding the development of new products and services.”

New products and services mean new jobs, in theory. This will “likely limit AI’s impact on unemployment”, it argues. It admits a “great deal of uncertainty over the figures”, but suggests the peak rise in unemployment will be in the low hundreds of thousands and not materialise until the late 2030s. “Previous waves of tech innovation have seen these two forces balance out, but how much that happens and how fast could vary greatly. Policymakers therefore need to think now about how to manage these challenges and opportunities… The government [should] speed adoption of AI to ensure benefits are distributed widely, and upgrade support [for] workers to match the pace of change.”

On workforce training and skills, the paper proposes every worker in the UK has access to a so-called ‘early awareness and opportunity system’ (EAOS), managed by the Department for Work and Pensions, for citizens to check how AI is likely to affect their jobs, and offer information on opportunities to use existing skills to retrain and progress. The Treasury should also provide state funding as an “income buffer for unemployment”, where AI takes jobs. It dubs this new public/private funding resource as ‘lifetime income flexibility and employment savings programme for adaptive needs’ (LIFESPAN), and implies the money should be somehow sourced promptly.

It says: “These funds would be structured in a similar way to private pensions, with workers auto-enrolled and paying a fixed proportion of their pre-tax income into them – to benefit from tax efficient saving. But unlike pensions, workers would be able to draw down their LIFESPAN funds prior to retirement in response to major life events (redundancy, parental leave, retraining) where they are temporarily out of the workforce. This would provide them with a personal safety net to finance re-employment and help ensure the workforce is more resilient to changing working patterns.” And AI has a role to play here, too, it says – to help workers attain more skills and live healthier lives.

“It could improve skills by increasing educational attainment by up to six percent and by providing tailored on-the-job training,” it writes. “And improve health by enabling early and predictive diagnoses, expanding health-system capacity and increasing labour-market access for people with different abilities.”

Sam Sharps, executive director for policy at TBI, said: “Much of the debate around AI’s impact on the labour market has been focused narrowly on its potential to displace jobs. While some job losses are likely, they should be viewed against the potential of AI to also create new jobs, improve worker health and skills, and significantly raise economic growth. One thing that is not in doubt, however, is that the UK will need to upgrade its labour-market infrastructure to cope with the higher rate of churn and more dynamic pace of change that AI is likely to create… The government now needs to face up to the future and make sure workers are ready for the impact of AI on the jobs market.”