The First Responders Network Authority is planning to award a contract for a new, nationwide public safety LTE network to a commercial partner by November 1, with caveats that the service will start out as essentially a mobile virtual network operator and eventually shift onto a new Band 14 LTE network as it is built out. Commercial roaming is seen as an essential component along the way.

The FirstNet network is relying on the value of its 20 megahertz of 700 MHz spectrum to attract partners. The idea is that excess capacity not needed by public safety can be leveraged by the partner to either bolster its own network or lease access to others (either other commercial entities or potentially “Internet of Things” solutions) – with the caveat that public safety traffic is prioritized and able to preempt other users on the network in emergency situations.

This could pose some interesting questions for the business case use of that excess capacity; T-Mobile US, for one, has expressed it is more interested in traditionally licensed spectrum through the ongoing 600 MHz auction than pursuing the FirstNet option. But, it also raises the issues of the roaming relationship between FirstNet and commercial LTE networks; LTE network design principals to ensure robust coverage and availability; and the fact that for most public safety agencies, FirstNet will be the first time they will have access to an LTE network they have any measure of control over – and it’s quite different from their land mobile radio networks.

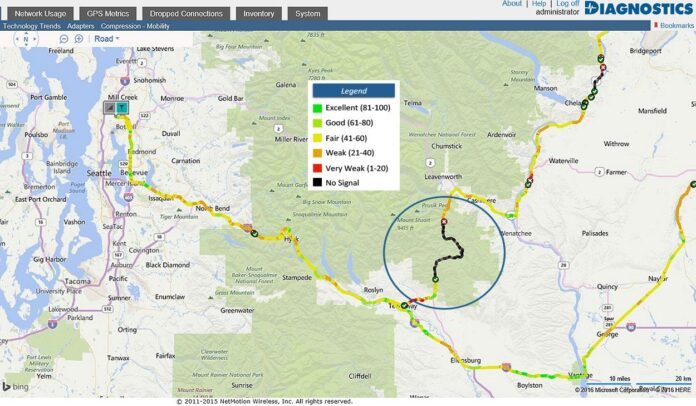

NetMotion Wireless has conducted drive testing of early Band 14 networks and also done testing designed to demonstrate typical LTE network coverage issues. NetMotion measured commercial carrier coverage outside of Seattle on mountain highways, which are often a difficult coverage environment: the company found stretches as long as 30 miles with no cellular coverage. Ubiquitous coverage is sure to be a challenge for FirstNet and its carrier partner as the network is built. Tests by P3 Communications, for example, found the JerseyNet early builder project was able to provide mostly “fair” coverage and some areas of good and poor coverage with three sectors, while in the same area Verizon Wireless was offering substantially more “good” coverage (based on reference signal receive power measurements) in the same area with 20 sectors.

LTE, noted NetMotion CTO Joe Savarese, is interference limited by design. The interference from LTE users and other sources can be significant, requiring network engineers to monitor the signal-to-interference plus noise ratio as it impacts system performance and the ability to transmit data. Adding to this problem, the farther a user is from the cell center, the more their experience is impacted. In remote areas and those with geographic challenges such as hills and valleys, coverage is particularly prone to spottiness.

“You’re never going to have perfect wireless coverage. It’s just not going to happen,” said Savarese. “You’re still subject to the laws of physics.”

In terms of network planning needs, NetMotion says most public safety agencies don’t have a good sense of their current usage patterns when it comes to data consumption, signal strength and SINR at different locations within the network so they may be hard pressed to outline their coverage needs for FirstNet. The company is currently supporting data collection by public safety agencies using its NetMotion Diagnostics tool to identify usage patterns and network problems.

NetMotion’s drive testing around the Seattle area, where one could reasonably expect good LTE coverage from a fairly mature network, assessed signal-to-interference plus noise-ratio continuity, since SINR is highly correlated with network performance. The company did see that as SINR rose and fell, so did throughput – and ultimately, Savarese said, situations with poor SINR resulted not only in lower speeds, but in fewer users that can be supported by the LTE system.

“If you have a system that’s in a best case, 10 [megabits per second] and you’re in a poor coverage area or in a high interference area, now that’s not 10 – it’s maybe 1 Mbps,” Savarese said. “That’s going to impact the number of users you can have. It’s really important to be able to limit the number of users and/or prioritize their traffic, for this reason.”

Steve Fallin, senior product manager at NetMotion, noted FirstNet will start out, as many of the early builder projects have, with small numbers of public safety users and eventually transition to larger numbers of both public safety and commercial users. Savarese expects that access class-based differentiation will have to be made so non-public safety devices with Band 14 capabilities actually stop trying to access the network for some period of time so public safety devices can get on.

Minimizing coverage gaps will be particularly important for FirstNet, he added, as many public safety applications can only tolerate a small amount of time disconnected from the network before they crash, reset or a virtual private network requires a new log in. (NetMotion provides VPN software to ensure continuity in such coverage situations.)

Prioritizing traffic doesn’t solely happen in the radio access network, Savarese noted – it requires end-to-end assurance. Connection via the Internet isn’t going to provide the necessary security and priority, so he expects to see something along the lines of MPLS-type connections to maintain prioritization within FirstNet – and, he added, it raises the question of how FirstNet traffic priority and security will be maintained when users roam on to commercial networks in areas where Band 14 coverage is poor or nonexistent.

FirstNet RFP responses are due by May 31, and the contract award is expected to be made Nov. 1.

FirstNet and the challenge of ubiquitous LTE coverage

ABOUT AUTHOR