Cellular technology companies with substantial device businesses — including Huawei and Samsung today, and Nokia until it sold its handset business in 2014 — generate no more than modest net licensing revenues, despite the significant Standard-Essential Patent (SEP) portfolio sizes they have declared. Crucially, they must also cross license their manufactures against infringement of other companies’ patents. Companies without significant device businesses, including Qualcomm and InterDigital, have no such overriding need to barter their intellectual property. Instead, they are focused on licensing cellular and smartphone patents for cash, upon which their technology developments crucially depend.

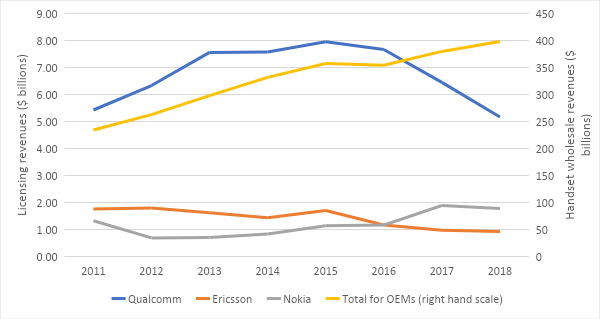

SEP licensors do the costly technology developments that make new generations of standards including 3G, 4G and 5G openly available to all OEMs: however, since 2011, if not earlier, none of the former has received, in licensing revenues, even as much as an average of $4.50 per phone or a few percent of global wholesale handset sales revenues, for example, totalling $398 billion in 2018. Aggregate royalties paid to all licensors have averaged less than five percent. In contrast, Apple has taken up to 43 percent revenue share with its iPhone sales and other smartphone leaders Samsung and Huawei are also currently in double digits.

Leaders’ technology licensing and OEMs’ total handset sales revenues in cellular

FRAND rates and net payments in cash

Some licensors legitimately generate rather more licensing income than others. Net royalty rates charged, and cash payments received, by the same licensor may vary substantially from licensee to licensee without violating Fair Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory (FRAND) licensing obligations.

The question of what levels of royalty rates should be deemed FRAND for licensing SEPs in cellular technologies has loomed large in commentary on the recent US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) v. Qualcomm antitrust trial in the Northern District of California. Witness Huawei claimed 80% to 90% of its SEP royalty payments are made to Qualcomm. Apple previously claimed Qualcomm charged it at least five times more in payments than all other cellular patent licensors combined. That was until Apple unilaterally withheld all such payments a couple of years ago. Notwithstanding the April 2019 settlement of all litigation between Qualcomm and Apple and with resumption of licensing payments to Qualcomm, including a one-off payment of between $4.5 billion to $4.7 Billion, the court’s decision in the above case is imminent.

It should be expected that some companies net much higher licensing rates and generate much more licensing income than most others. It should not be considered untoward or a violation of FRAND or antitrust requirements. FRAND rates negotiated bilaterally or multilaterally, let alone licensing payments made after netting off parties’ charges, may vary substantially from case to case due to different business models, patent holdings cross-licensed, payment timing and disparate trade flows of products licensed, manufactured and sold among SEP licensees. Substantial differences in net rates and payments can therefore be quite legitimate due to various quid pro quos, as well as differences in patent portfolio sizes and strengths.

Major OEMs would rather limit rates to minimize out-payments than maximize royalties received

Companies with predominantly downstream business models as device OEMs, that implement numerous SEP technologies, tend to benefit from generally low royalty rates, even if they have substantial patent holdings themselves. Many device OEMs have, accordingly, tended to advocate licensing regimes that cram down royalty charges by capping aggregate royalty rates. As I have explained in my publications for more than a decade, SEP owners with large device businesses prefer to limit rates, even though that limits them to generating only modest licensing fees, because low rates also minimise their royalty out-payments on those devices.

Market leaders in cellular handsets, including Nokia 12 years ago, Apple, Huawei and Samsung today, invariably have much larger market shares in featurephone or smartphone sales than they have shares of SEPs reading on the cellular standards. They are therefore far more financially exposed as licensees than they stand to gain as licensors — particularly in negotiating licensing agreements with other SEP owners that have no downstream device business in need of licensing. Even though some of the above companies are also major patent owners, their royalty incomes were or are modest in comparison to licensors without downstream operations producing or selling devices.

Patent pools

Patent pools provide notable evidence of this downstream effect with their rates tending to be much lower than bilaterally negotiated rates. Patent pools are typically dominated by leading implementers of the applicable standard and that may also own many SEPs reading on that standard. For example, MPEG LA lists Apple, HP, Panasonic, Samsung, Sharp, Sony, Toshiba and ZTE among its many licensors for the very popular AVC/H.264 video standard employed in smartphones and TVs. Its maximum rate is around $0.20 per unit sold including smartphones, PCs and TVs.

Royalty-free joint licensing, very similar to pooling in many ways but without the need to check patent essentiality or collect and distribute royalties, is an extreme case of this downstream effect. The Bluetooth Special Interest Group allows its members royalty-free implementation of this popular standard so long as they also commit to license their patents on that basis.

Some joint licensing arrangements, also very similar to pools, are not dominated by the applicable standard’s implementers. Major SEP licensors in Avanci are companies that do not manufacture automotive products including Ericsson, InterDigital, Nokia and Qualcomm. It was telling, and quite self-serving, that the Huawei speaker at the recent TILEC recent conference on patent pools asserted that Avanci’s cellular-SEP licensing charges [of $3 to $15 per car] are too high.

Patent pool benchmarks were, at first, presented by TCL in its FRAND licensing rate litigation versus Ericsson in the Central District of California. But the dynamics of patent pools were totally inapplicable to this dispute about bilateral rates. Patent pool licensing rates were never even considered by the Court because these, following my expert rebuttal report, did not even make it into direct testimony at trial.

Proportional allocations

SEP owners with major downstream operations commonly also contrive for apportionment so that, for example, owners of only few SEPs can command no more than very low rates. This action was, among other reasons, to counter some OEMs with small patent portfolios punching way above their weight in cross-licensing negotiations with large SEP holders who were also seeking freedom to operate with low patent infringement risk as major device OEMs. For example, Nokia had a $50 billion handset business in its heyday approaching and including 2008. The threat of litigation from small patent holders against such a large amount of trade made it impossible to achieve anywhere near Qualcomm’s rates when Nokia sought to license them for use of Nokia’s SEP technology. In contrast, Qualcomm exited the handset business many years earlier around the turn of the millennium.

If it ain’t broke don’t price fix it

Antitrust authorities, including the FTC, should not be price setters. Instead of adjusting established royalty rates—underpinned by hundreds of licenses and billions of dollars in payments over many years—applicable questions for these organizations are: is the market competitive, efficient and maximizing consumer welfare? Copious evidence shows that it is: with relentless market entry and disruption to incumbents, ever-improving quality and declining prices. The unintended consequences of price regulation would harmfully disincentivise new-technology investments in standard-essential technologies that could be exploited by the entire ecosystem of suppliers and consumers at very low incremental costs in comparison to product and service prices.

FRAND rates and payments differ with variations in other licensing terms and trading volumes

FRAND licensing must accommodate a wide variety of factors. Rates and payments can vary substantially among different pairs of licensors and licensees – even for the same patent portfolios — because other contractual terms and trade flows for licensing vary so much (i.e. how many handsets manufactured and at what prices sold by each party). But that does not mean that anything goes. The words fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory still have meaning— it is just that the detail with various offsets and other factors is devilish and can account for major differences in apparent royalty rates and actual payments – particularly between licensors that are predominantly that, and those that are largely major implementors and patent licensees as device OEMs.