Allconnect’s survey suggests that black, Hispanic Americans are significantly more likely than white Americans to not have internet connection

A survey conducted by Allconnect, an online broadband marketplace, revealed that race and income are the biggest factors that determined if a household had adequate internet connection. Specifically, black and Hispanic Americans are significantly more likely than white Americans to not have internet connection at home, and households earning more income report higher rates of connectivity and faster connections overall.

Having access to reliable internet has, for some time now, been considered a human right by organizations such as the United Nations; however, the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced us all to work and learn from home, brought into sharp focus the severity of America’s digital divide and the devastating consequences of poor connectivity, especially for students.

To drive this last point home, Allconnect referenced a Benton Institute paper that claims that the gap in digital skills between students with no home internet access or cellphone only and those with home internet access is equivalent to the gap in digital skills between 8th and 11th grade students.

“On average, students with fast home Internet access report an overall grade point average (GPA) of 3.18. This is significantly higher than the average 2.81 GPA for students with no access and the 2.75 average for students who have only cell phone Internet access,” the paper also states.

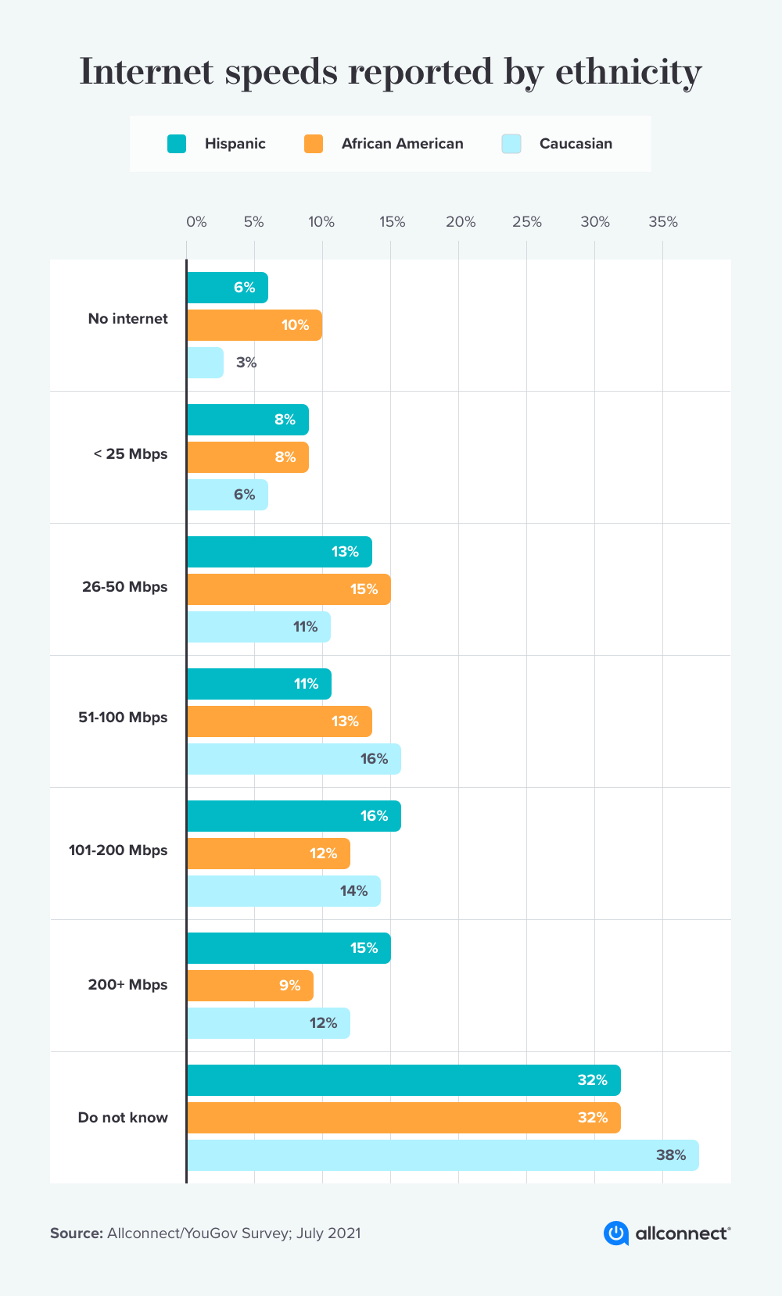

Of the more than 1,200 adults surveyed, only 5% of respondents indicated that they didn’t have a home internet connection. When broken down by race, however, Allconnect found that roughly 10% of Black respondents didn’t have any internet connection at home, while 6% of Hispanic respondents said they had no connectivity and just 3% of white respondents said the same. These numbers show that black respondents were three times as likely to not have internet as white respondents.

And for those black and Hispanic Americans with internet connectivity, many of them reported much slower speeds than white Americans. According to the results, 8% of Black and Hispanic respondents reported getting less than 25 Mbps — below the FCC’s definition of minimum broadband speeds — compared to 6% of white respondents.

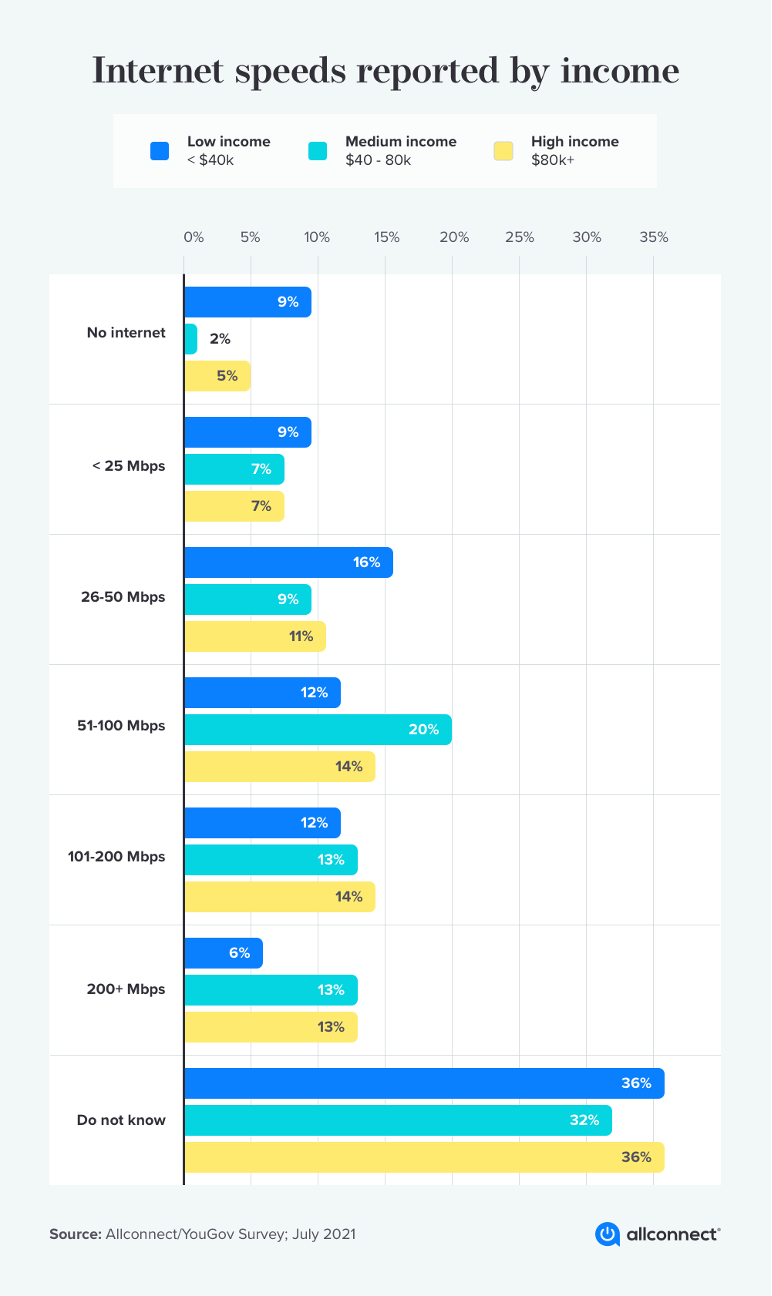

Additionally, Americans making less than $40k a year were twice as likely to not have internet at home than households with higher incomes. Nine percent of those making below $40K had a connection under 25 Mbps, 7% for those making between $40K and $80K has no internet connectivity, while only 4% of those making about $80K said the same.

In the past, the focus of many rural broadband initiatives has been around improving access and increasing infrastructure. While this is critical, surveys like these show that the digital divide is often an issue of cost, as well.

To address this problem, several service providers like AT&T, Cox, Altice and Spectrum offer discounted plans for low-income household. Further, as a result of the pandemic, the federal government invested an unprecedented $10 billion in abolishing the digital divide with $3.2 billion coming in the form of the FCC’s Emergency Broadband Benefit (EBB), which provides a direct subsidy of $50 a month to households earning less than 135% of federal poverty guidelines, or anyone who lost their job during the pandemic.

Tammy Parker, senior analyst at data and analytics company GlobalData, said that the EBB program “signals an emerging focus on broadband affordability rather than just accessibility. … In years past, the regulatory focus has largely been on expanding availability to bring unserved and underserved areas into the digital pipeline. However, COVID-19’s economic and societal impacts highlighted the economic inequities around broadband. Even when service is available, potential end users may not be able to pay for it.”