The Baker to Vegas Challenge Cup Relay pushes people to the edge; Verizon Frontline is there not just with tech, but with trust

DEATH VALLEY—It was me, Dan Jones from Fierce Network, Eric Durie who’s the associate director of communications for Verizon Frontline, and Guadalupe Vicon, a senior manager of communications on the consumer side of Verizon’s business. We loaded into Eric’s rental SUV and left the Rio in Las Vegas for Death Valley to take a look at Verizon Frontline’s field operation and deployables for the Baker to Vegas relay. Vicon—that’s what she goes by—fired up “A Horse With No Name” by America, and we were off. But let me back up a little bit.

The Baker to Vegas Challenge Cup Relay is a 20-stage footrace from Baker, Calif., to Las Vegas, Nev. More than 200 teams—each with 20 runners—grit it out over 120 miles of blistering desert highways and steep mountain passes. They do it for three reasons: to win, to raise money for the school in Baker, and to win. Behind them are hundreds of volunteers, medical staff, race coordinators, and Verizon Frontline’s pop-up infrastructure—and the team that sweats (or freezes) it into place.

The day before we headed out into the field, I chatted with Paul Wood, crisis response senior manager on Verizon’s Frontline Crisis Response Team. This isn’t his first relay and he’s well-versed in the complexities of delivering an available, reliable network largely to support the potential medical needs of the racers. He recalled a Baker to Vegas a few years back when he was setting up a manual-aim satellite dish to feed capacity to an eFemto-cell and create a bubble of connectivity where none existed before. That was at stage nine of the race, a 7.5 mile stretch that begins about 15 miles south of Pahrump, Nev.

Wood told me that, as he was setting up his bubble, a volunteer came up to him and said he needed to make a call, which Wood facilitated. The volunteer made the call, came back and told Wood his wife had had a cardiac event. But he was able to talk to her, talk to her doctors, understand the situation, and carry on with his volunteer duties. “The next year, working at the same stage, he comes up to me and introduces his wife to me,” Wood said.

“All this technology, all this stuff we have out here, when it comes down to it at the end, there’s people in front of it, there’s people behind it, and it matters to them.”

“We find that a lot of the time, what we’re providing coverage for, the actuality of it is it’s a lot less about the public safety comms and a lot more about the morale-boosting of talking to someone at home…It’s a pretty powerful thing to give people that peace of mind, that comfort.”

Comfort is hard to come by out here. You might find a bit of it at the Crowbar Café and Saloon in Shoshone, Calif.—population 20, give or take. But unlike most weekends, one thing you can find in this part of Death Valley during Baker to Vegas is tech. A lot of tech. We saw plenty of SPOTs—Satellite Pico-cells on Trailers. There were COLTs—Cells on Light Trucks. There were COWs—Cells on Wheels. And there was at least one STUD—Satellite Trailer, Universal Design. That one’s new.

A Verizon Frontline STUD–Satellite Trailer, Universal Design.

It has two satellite dishes—an on and an off—that track medium-Earth orbit (MEO) satellites, then beam signal through high-powered radios. The former Marine setting it up took a minute to explain onboard power, the cooling system, and the 100 gallons of diesel fuel it carries to stay operational. “They named it after me,” he said, as the sun beat down and dust whipped around us.

Back at the Rio the day before, I met with Race Coordinator Rick Santos of the Los Angeles Police Revolver and Athletic Club. This is his fourth year in the top spot for Baker to Vegas. “It went to shit the first year,” he said. “Coming back after COVID, it was extremely hot and some of the teams, I think, forgot about the hydration part.” Eventually, he had to make the call to pause the race—there just weren’t enough medical resources.

In addition to running the race, Santos also runs in the race; even on race day he’s taking on an early stage. Talking through the relationship with Verizon Frontline, he said, “They’ve jumped up big time. Our primary line of communications across the entire race course is with Verizon…Working with Verizon Frontline has ensured that we are definitely one of the safest races…This type of footprint, with doctors at every stage, with Verizon Frontline out there, there’s coverage in spots where we thought we’d never have coverage.”

Verizon Frontline team members prep a SPOT, and other equipment, at a staging area in Pahrump, Nev.

We met up with Curtis Mentz, associate director of Verizon Frontline Crisis Response Team for the West region, at the Holiday Inn Express in Pahrump. He’s been with Verizon for 37 years—since before it was Verizon. He’s a certified emergency medical technician and volunteers doing search and rescue in San Mateo County, Calif. He hopped into his white Suburban and told us to follow him out to the medical base. We pulled off the highway a few times to chat with some of the Frontline crew. He knew everyone’s name, he kept things light, and he kept things going.

Following Curtis Mentz along the race route–he knew exactly where he was going.

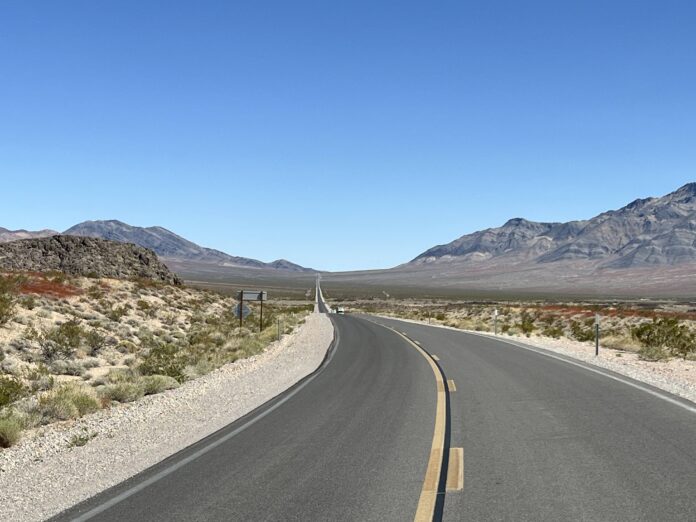

One of our stops was near Chicago Valley, stage 8 of the race, a 6.6 mile stretch. “This would be my stage,” he said, encouraging me to go stand out in the road and take it all in. Running that would induce a “catatonic” state in him, prompt him to talk to a higher power, Mentz said. I’m not a religious person but if anything would do it, it’d probably be running down that stretch of Highway 372.

Like Wood, Mentz also had a story of a Baker to Vegas past. He was out pre-flighting the route when he encountered a disabled motorist with a flat tire. Mentz helped them change the tire, but the spare was also low on air. With a SPOT in tow, he followed them to a nearby-ish Chevron station to make sure things were all sorted. “We like layers of redundancy…PACE,” he called it. “Primary, alternate, contingency, emergency.”

Baker to Vegas is objectively interesting—and in the narrower context of what Verizon Frontline does, it’s even more so. They obviously deliver a huge impact by providing end-to-end comms, but it’s also an opportunity for them to test out new equipment and architectures, train up new crew members, and otherwise do something that’s good for people. That’s the type of thing you can do on bluesky days. But they’re not all bluesky days; there are a lot of darksky days too.

Talking about the relay, Wood said, “We don’t view it as an incident. It’s a training exercise/experience. But it also has real life and death possibilities on race days.” Verizon Frontline responded to around 1,500 incidents last year. In 2023, Mentz’s team mobilized for the devastating Hawaii wildfires that killed more than 100 people, and leveled the town of Lahaina on Maui.

Part of the recovery effort there involved using drone-based cells to establish connectivity while terrestrial infrastructure was brought back online. That process was repeated down the coast until communications were restored. Mentz recounted how his colleagues had to charter a cargo plane out of LAX, load it up with the types of assets we saw in Death Valley, get it to Honolulu—the runway at the Maui airport isn’t long enough to accommodate the aircraft—then get it on a barge over to Maui.

The ability to shift mindset, to answer a call at midnight and roll out, kind of explains why so many of the Verizon Frontline team are former military and former law enforcement. That put things into perspective for me—what was happening in the desert was certainly serious, but most of Verizon Frontline’s day-to-day is much, much more serious.

The whole Baker to Vegas Challenge Cup Relay embodies that bluesky/darksky contrast. “This whole weekend,” Santos said, “what it provides for coppers is just an outlet…360-something days out of the year, a lot of these guys are pushing a black-and-white, and answering the calls, and dealing with peoples’ worst days of their lives…These cops carry that. They’re human beings and they carry that weight of everything throughout the year.”